How Russia’s Black Sea Fleet Could Change the Equation in Ukraine

The prospect of greater Russian involvement in the war in Ukraine raises questions about the possible role of Russia’s Black Sea Fleet and how it could support Russia’s Ground Forces.

The Russian Black Sea Fleet has seen something of a renaissance. While in 2000 it was seen to have been the lowest priority of Russia’s four fleets and its readiness was approximated at less than 50%, by the time of the 2014 annexation of Crimea, Russia’s Black Sea Fleet was able to play an important role in Russian operations and served to prevent Ukrainian ships from returning to their ports.

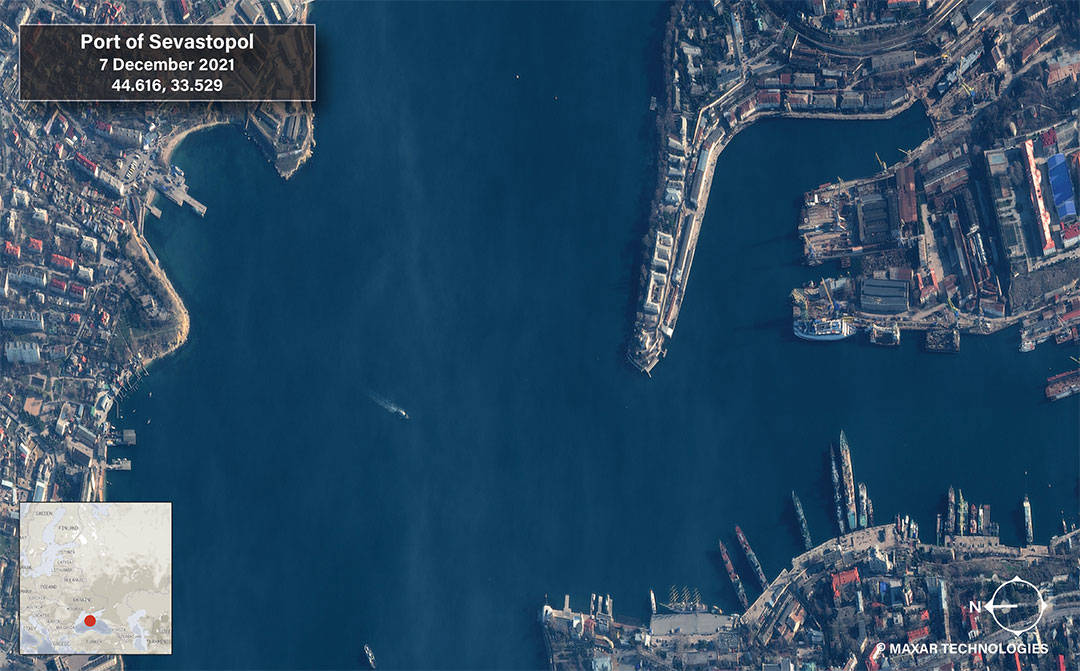

Figure 1: Maxar satellite imagery taken of the Sevastopol naval base on 26 November. Sevastopol is the home of the Black Sea Fleet.

In April 2014, President Vladimir Putin ordered a ‘development programme’ for the Black Sea Fleet, which led to the production and delivery of four Project 22160 patrol ships by 2021, with two further vessels expected by 2023. Three Admiral Grigorovich-class guided missile frigates are now a part of the fleet and have participated in drills with the Egyptian navy and conducted anti-submarine warfare drills in partnership with the Slava-class guided missile cruiser Moskva. The Admiral Grigorovich-class has UKSK vertical launch cells capable of launching both 3M-54 Kalibr (SS-N-27 Sizzler) subsonic cruise missiles as well as the P-800 supersonic anti-ship missile, in addition to possessing an air defence capability. The Moskva also carries P-1000 Vulcan supersonic anti-ship cruise missiles as well as 3M41 Fort long-range air defence missiles, among a host of other guided weapons.

The fleet’s larger number of smaller vessels also possess substantial long-range strike capabilities. Its Project 12411 (Tarantul) and 21630 (Buyan) corvettes can launch SS-N-22 Sunburn anti-ship missiles and the Kalibr, respectively, and the Project 22160 can mount containerised Kalibr launchers. In effect, the Russians have built a fleet in the Black Sea that can deliver effects at reach despite not being comprised of major surface combatants. The decision to arm even relatively small vessels with potent strike capabilities means that the fleet can contribute to both regional sea denial and long-range precision strikes. The Caspian Sea Fleet’s Buyan corvettes, for example, launched Kalibr cruise missiles against Syria in 2015.

From 2014 to 2016, the fleet received six improved Kilo-class diesel attack submarines that also provide launch capabilities for Kalibr missiles, as well as 533mm torpedoes. Though lacking air-independent propulsion, these vessels are quiet and are generally regarded as being very difficult to detect in littoral waters. They substantially outmatch the regionally deployed subsurface assets of riparian navies – their primary task given that the Montreaux convention prevents non-riparian states from deploying submarines to the region. Over the last several years, some of the fleet’s Kilos have operated out of Tartus, with the intention likely being to make this deployment a permanent feature of the Black Sea Fleet’s activities.

Finally, the fleet’s 126th Coastal Defence Brigade operates the ground-based Bastion-P missile complex (SS-C-5 Stooge), which launches the P-800 Oniks and may be equipped with a longer-range 800km Oniks-M. These missiles are likely to receive cuing from airborne assets like UAVs, as well as low observable vessels like the Project 22160. In addition to substantially raising the risks of deploying vessels near Crimea, they can also play a land attack role.

The Russians have in effect built a fleet in the Black Sea that can deliver effects at reach despite not being comprised of major surface combatants

Suffice to say, the Black Sea Fleet has been significantly recapitalised and can theoretically both challenge the ability of NATO forces to enter the Black Sea and create problems in the Mediterranean. Although it is far from clear how the fleet would support a Russian escalation in Ukraine, several options present themselves.

Figure 2: Maxar imagery of a Russian training ground near Pogonovo. It appears to show four K-300P TELs with their missile launchers elevated. The reason for their presence is not clear.

One possibility is in the provision of precision strike capabilities for Russian Ground Forces, either from vessels at sea or through the provision of ground-based assets. Maxar satellite imagery from 16 November appears to show four K-300P Bastion-P coastal defence missile launchers located at a training ground near Pogonovo. This is a long way from the coast, and while the P-800 Oniks missile launched by the Bastion is notionally a supersonic anti-ship missile, it has been demonstrated in the land attack role in Syria. It is possible that the Russian forces have practiced integrating the system into their reconnaissance-strike complex, which connects cross-domain reconnaissance assets to long-range strike to engage high-value targets such as command-and-control nodes, critical infrastructure and other assets central to an opponent’s way of war.

The use of long-range strike against politically sensitive targets is also central to the Russian approach to managing escalation and localising conflicts. Russian authors write that strikes on high-value targets can be used to remind both the immediate adversary and potential interveners of the risks of escalation if the conflict is not brought to a swift end. They thus reinforce the strategy of presenting opponents with a rapid fait accompli by incentivising de-escalation after Russia has secured its aims on the ground. Strikes on targets deep within Ukraine might, then, accompany a shallower ground assault that secures local gains near the border.

The Black Sea Fleet has established form in supporting ground forces: the Moskva, for instance, was used to provide air defence for the approaches to the Syrian coast and completed multiple combat tours in support of Russia’s operations in Syria. The Rostov-No-Donu submarine also fired four Kalibr cruise missiles from a submerged position against targets in Syria, demonstrating the ability of the Black Sea Fleet to project force. The fleet also supported Russian forces during the 2008 war with Georgia: a squadron headed by the Moskva reached the Georgian coast by 9 August – just one day after fighting commenced. It was reportedly engaged in a skirmish with Georgian coastal defence vessels and provided overwatch for an amphibious landing of Russian troops.

A more ambitious objective in Ukraine might be an amphibious assault against Odessa. There would certainly be a strategic rationale for this – if Russia is to accept the likely substantial economic costs of a war with Ukraine, it needs to secure some form of permanent leverage over the country’s foreign policy that would be of commensurate value to the costs of war. It is not clear that further limited aims in the east would accomplish anything that the war in Donbas could not. Possession of Odessa, however, would provide Russia with effective control over Ukraine’s maritime trade – given that the port handles 70% of the country’s shipping and few viable alternative ports exist – and thus give it a long-term veto over Ukraine’s foreign policy. The area, with its large Russian population, may be viewed by the Russians – correctly or otherwise – as likely to be quiescent in the face of such a change.

If the Black Sea Fleet was used for an amphibious invasion, could its capabilities support such a complex operation? The fleet has seven ageing Ropucha-class and Alligator-class amphibious vessels. The former are capable of carrying 340 troops and up to 10 main battle tanks (MBT) or 12 BTR-80 amphibious armoured personnel carriers (APC). The Alligator can carry 313 troops and either 20 MBTs or 47 BTR-80s. Four Ropuchas from the Baltic Fleet and Northern Fleet, as well as eight landing craft from the Caspian Sea Fleet, joined the Black Sea Fleet for exercises in April this year – though it is not clear how many remained in the region. If Russia did build up a force comparable to the one that executed exercises in April, this would give it the lift to move around 3,600 troops, all of the Crimean Naval Infantry Brigade’s likely outfit of 70 MBTs as well as up to 153 BTR-80 amphibious APCs in a first wave – though in practice slightly fewer vehicles might be carried to create space for supply trucks. This force, while not particularly large, would presumably benefit from naval gunfire support and air superiority if, as is likely, Russia established local sea and air control first.

In a worst-case scenario, the Russian build-up on the ground may be a feint for a highly consequential amphibious assault

Going by previous exercises, an assault would begin with an initial wave comprised of helicopter-borne subunits from the Sevastopol-based 810th Naval Infantry Brigade, tasked with seizing and clearing a beachhead to allow tanks, Nona howitzers and Tornado-G MLRS systems to be brought ashore. The Mi-8 AMTSh helicopters supporting these exercises would have to operate from Crimea, as Russia lacks helicopter-carrying amphibious ships. Both tanks and artillery have been coordinated with UAVs for indirect fire to hold a beachhead, and would be backed by naval gunfire and airstrikes. In essence, given the limited lift capacity at Russia’s disposal, its forces need to compensate for mass by maximising firepower both from within their formations and from other sources. Such a force could not storm a well-defended city, but it could try to secure airheads or port facilities to allow follow-on forces to be flowed in. The seizure of a beachhead and a push several kilometres inland to seize Odessa’s airport, for example, would enable the movement of follow-on forces to besiege and take the city.

The major challenge for any Russian amphibious effort is a lack of large assault vessels equipped with the command-and-control suites, ability to carry helicopters and storage space for supplies typically needed to conduct and then sustain an assault with a high degree of confidence. The proximity of Crimea to likely targets partially offsets this, but it remains a weakness. Russia’s last amphibious operations in 2008 occurred against uncontested shores – and still involved substantial difficulties. Since then, the major function of the Ropucha class has been ferrying supplies to Syria. Russian efforts to fill this capability gap with the French Mistral class fell through in 2014, with the domestically produced Ivan Gren – a much smaller vessel – only partially offsetting this loss. The Ivan Gren is not currently with the Black Sea Fleet, though it could join it. Finally, Ukraine possesses a limited capacity for sea denial through ground-based missiles – raising the risks of at least some losses which could be critical to an already small amphibious force. As such, for an assault to occur, Russia would need two preconditions to be met. First, the Russian Aerospace Forces and Black Sea Fleet would have to establish a level of air and sea control sufficient to offset the limited size and supplies of an initial wave until an airhead or port was seized. Second, the build-up in the east needs to draw away enough of Ukraine’s armed forces to leave the country’s southern flank underdefended – much as the 2014 build-up on Ukraine’s eastern border drew its attention and troops far away from Crimea. Even then, this would be a high-risk option for Russia – albeit one with significant rewards.

Finally, the Russian Navy’s contribution could take the form of actions geared toward both signalling towards the West and rolling back Ukraine’s military development. In 2008, for example, a major objective of Russian air operations was rolling back Georgia’s military development by destroying key infrastructure and setting the conditions of the post-war order. The Russian Navy might be tasked with, for example, targeting key Ukrainian ports and shipyards, both to restrict the country’s long-term military options and as a diplomatic signal to its partners. It might also opt to maintain a post-war blockade or a limited quarantine to preclude arms supplies reaching Ukraine, mirroring its approach in the Sea of Azov.

Though much attention has been paid to the recent build-up of Russia’s Ground Forces – and rightly so, as they are still likely to be the sword arm of any eventual clash – there is cause for more carefully monitoring the Black Sea Fleet’s activities. In a worst-case scenario, the build-up on the ground may be a feint for a highly consequential amphibious assault. Even if this is not the case, the fleet will likely play an important role in any Russian strike campaign against targets across the breadth of Ukraine. While little can be done to affect the material balance of power in the short term, the best NATO can do is maintain and share with the Ukrainians situational awareness regarding the movement of vessels – particularly amphibious assets like the Ivan Gren – towards the Black Sea. In the longer term, NATO partners might consider supporting Ukrainian efforts to build up their sea denial assets.

The views expressed in this Commentary are the authors', and do not represent those of RUSI or any other institution.

Have an idea for a Commentary you’d like to write for us? Send a short pitch to commentaries@rusi.org and we’ll get back to you if it fits into our research interests. Full guidelines for contributors can be found here.

WRITTEN BY

Dr Sidharth Kaushal

Senior Research Fellow, Sea Power

Military Sciences

Sam Cranny-Evans

RUSI Associate Fellow, Military Sciences