US and UK Intelligence and Security Relationship: The Way Forward – Together

Whoever wins today’s ballots in the US, one element will remain rock-solid: the UK–US security and intelligence partnership.

US election day is upon us. We now see much discussion of the US’s relationships with longstanding allies across the world and the advantage such alliances bring, both to the US and to the countries involved. There are some who question the future of these alliances, including the continued resilience of the closest of all – that with the UK. These questions prompt me to reflect on my personal experience of the Special Relationship and its durability for the future.

On 15 November 2016, one week after the last presidential election, I spoke to a large audience at Queen’s University in Charlotte, North Carolina. I shared the platform with General Michael Hayden, former director of the NSA and the CIA, and a close friend. We discussed our mutual experience of working together to protect and promote the national security of the US and the UK. Towards the end, I felt challenged to clarify my understanding of the Special Relationship. I spoke impromptu as follows: ‘All my professional life I have bet on my country’s relationship with the United States of America. This is not going to change’. There was immediate impact. The audience stood en masse and cheered me off the stage – an emotional moment.

I first met colleagues from the CIA in 1979 as a young officer at the age of 30, so quite early in my professional career. I had already been engaged in an operation providing valuable intelligence which my service shared with the CIA. I learned early on that we did not always agree with our US colleagues on operational tactics and decisions and that each of us was naturally inclined to protect our independence of judgement. As services in exceptionally close contact, we were also vulnerable to mutual stereotyping, such as for being over-adventurous and risk taking, or for being risk averse. But I understood from the beginning that this relationship was exceptional and based on decades of shared experience and activity across all our national agencies.

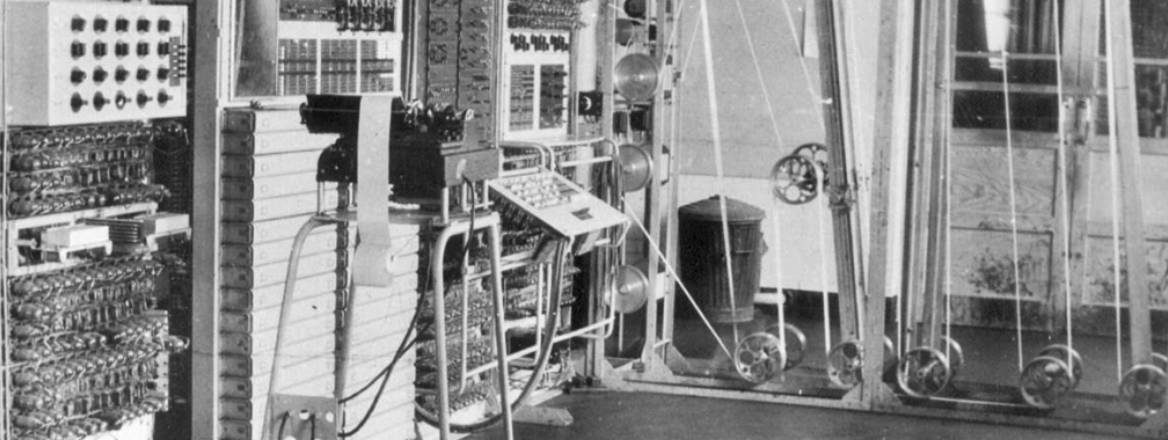

In later years, I came to learn more about our shared history. Notably, on 8 February 2016, as chairman of the Bletchley Park Trust, I attended, with the directors of GCHQ and the NSA, a ceremony and BBC interview in the office of the wartime director and effective founder of Bletchley Park, Commander Alistair Denniston. The event was to celebrate the 75th anniversary of the arrival (in that same office) of US code breakers who came to exchange our most secret assets, the breaking of the Enigma (German) code and the Purple (Japanese) Machine. If there was a beginning of the Special Relationship, this was it. It was the first step to the BRUSA intelligence relationship (March 1946) and eventually the Five Eyes.

As my career continued, I worked directly or indirectly with US colleagues on a whole range of issues and threats from classic Cold War strategic reporting, to the end of Apartheid, conflict in the Balkans, Afghanistan, Iraq and, of course, jihadi extremism and terrorism after 9/11. Together, we experienced the opportunities and complexities presented by rapid technological change. Throughout these years of collaboration, I saw how our relationship was based on mutual respect for each other’s qualities and capabilities. In terms of available resources, of course, it could not be balanced. I was always aware of the vast resources available to my US colleagues, the responsibilities they carried as a result and the generosity they displayed to the great advantage of the UK’s safety and security.

Our collaboration and relationship were not always straightforward. There were certainly ups and downs. Throughout the Cold War both sides suffered from major espionage penetrations (although the British failures tend to be better known). Subsequently, counterterrorism work and operations in South Asia and the Middle East brought high levels of tension and public/political controversy. But, in my experience, these difficulties never undermined the fundamental strength of the relationship. Our ability to speak openly and honestly to each other, to provide support and, where necessary, criticism, played a critical role.

This last observation goes to the heart of the relationship as it has existed over the past 70 years. On many occasions through these decades US and UK policy has not been fully aligned. The Suez Crisis in 1956 is one obvious example. But even then, the records show that we kept up the exchange of sensitive intelligence. The UK did not follow US policy in Vietnam; in the 1980s there was tension in the Caribbean and subsequent differences of approach in the Balkans. More recently, we have had different approaches to Libya and Iran. But, in my experience, and to my knowledge, these policy differences have not affected the underlying sense of commitment and collaboration shared by professional servants of the state.

This commitment has been, and remains, rock solid. The spirit of the relationship was well summed up by one of the US code breakers at Bletchley Park during the Second World War. Speaking many years later, and well after the Suez Crisis, this officer described how the relationship was based on personal trust and friendship without regard for the politics of the moment. He was confident this spirit would continue indefinitely. He was right. The commitment, trust and personal emotion apply now, just as they did then.

The UK and the US face a world of geopolitical change and uncertainty, accentuated by the pandemic. Liberal democracies are challenged by assertive, authoritarian states and non-state actors, above all perhaps by the remarkable rise and success of China. Our countries, our way of life and our values urgently need the leadership that only the US can provide. I know the UK will be there to provide essential partnership and support.

Sir John Scarlett was Chief of the British Secret Intelligence Service, and chaired the Cabinet Office Joint Intelligence Committee. He is RUSI’s Vice-Chair.

The views expressed in this Commentary are the author's, and do not represent those of RUSI or any other institution.

WRITTEN BY

Sir John Scarlett KCMG OBE

Distinguished Fellow