As the challenge posed by China’s technological advancement continues to grow, does the UK have the capacity to respond?

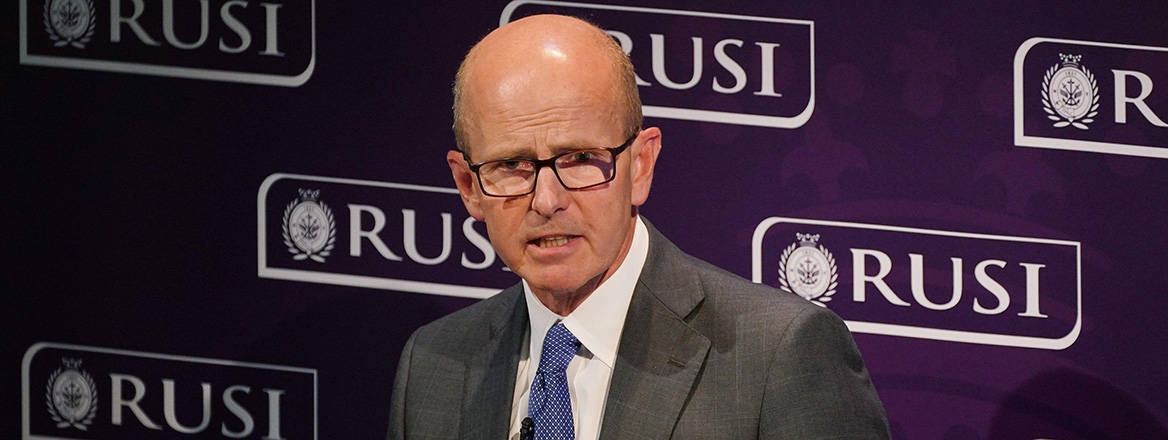

Last week, in a speech at RUSI, Sir Jeremy Fleming set out what he views as ‘the national security threat that will define our future’ – China and technology. Fleming’s speech outlined the breadth and complexity of China’s ambitions and capability in cyberspace, and what is needed from the UK and its allies to address this challenge. Undoubtedly, technological innovation provides a strategic advantage to countries who can harness its potential, and while it is to be expected that China would seek to exert its influence over the global ecosystem, the response from the UK remains unclear.

But does the UK even have the right resources to respond to China’s technological growth? While many inside and outside government are working on aspects of this critical work, there are gaps to be filled. The UK needs to invest in homegrown expertise and skills – not only in industry, as suggested by Fleming, but also in academia and government – to coordinate a whole-of-nation approach if it wants to stand a chance of competing.

Does the UK Have Enough Expertise?

While the UK’s world-leading sigint capability is undeniable, the pool of China, cyber policy and emerging technology experts remains small, if formidable. And what specialists do exist across government, academia and industry are often not positioned in a way for their expertise to contribute maximally to the UK’s long-term cyber aims. UK civil servant portfolios are generally structured so that they will either cover a high-level view of China, cyberspace and national security, or be focused on minutiae and specific operational aspects of a given topic. The UK is home to renowned cyber and technology policy academics who generally focus on niche aspects of their chosen disciplines and rarely look at China and cyber policy together. In industry, there are decreasing incentives to develop China expertise due to export controls and acts of cyber espionage by Chinese state actors. While the government has invested in building technical cyber capability, deep China policy and linguistic capabilities should be more greatly valued, and support should be given to put UK thought leaders and industry at the forefront of the rapidly evolving field of cyber and technology policy and innovation.

Can the Government Mobilise a Whole-of-Nation Response to the China Question?

The UK’s China, cyber and technology expertise is largely scattered across government, industry and academia. To date, there is no consistent mechanism through which to share insights, challenge assumptions or coordinate efforts. Much as the National Cyber Security Centre’s ‘Industry 100’ programme brings industry expertise in house, there should be a similar initiative to pull together policy experts from government, academia, think tanks, and industry. For existing expertise, programmes of interdisciplinary exchange with practitioners, academics and technical experts would go some way to ensuring we do not become as ‘blind men feeling the elephant’. Industry has a clear role to play in providing insight on what the next generation of consequential technologies are and driving international standardisation. Together with the government, they can identify the key standards organisations to engage in and the specific aspects of emerging technologies (such as AI and quantum) which the UK and its allies need to shape, as well as support the training of the next generation of technical standards experts. The government should act as a convener, encouraging these pockets of expertise to cross-pollinate through government, industry and academic collaboration by providing a platform for international thought leadership.

There are still many ‘middle-ground’ countries that are not fully aligned with either side, such as India and South Korea, and they are a key constituency for the UK and its allies

Are the UK’s Traditional Alliances Enough to Counter China in Cyberspace?

In recent years, the G7 and democratic countries' alliance vis-a-vis China has been strengthened. An effective response to China’s efforts to influence international technology norms needs to not only leverage the UK’s traditional alliances, but also reach out to so-called ‘middle-ground’ countries and appeal to the 40% of the world that has yet to cross the digital divide and come online.

There are still many ‘middle-ground’ countries that are not fully aligned with either side, such as India and South Korea, and they are a key constituency for the UK and its allies. Most countries that have significant internet populations are grappling with the amplification of existing and new challenges that digital technologies bring. From information security and algorithmic transparency to misinformation and cybercrime, governments across the world are trying to manage the opportunities and risks. The UK and its allies need to provide a credible vision of the internet that is not just defined in opposition to China, but also addresses these real challenges that all governments face, and consistently uphold the principles that underpin it.

The Chinese technological threat is not just about the race to lead in aspects of AI, quantum computing, or any other specific technology. It is also about competing for influence in emerging markets, where technological infrastructure choices made today will create path dependencies that Beijing hopes will keep these countries within its sphere of influence for decades to come. Building technology ecosystems in markets that are not yet fully connected to the internet will be done through two routes: de jure international technical standards such as those developed at the International Telecommunications Union (ITU), and de facto standards driven by the provision of infrastructure on the ground.

Regarding de jure technical standards, there has been a renewed effort in recent years by the UK and its allies to defend their position at the ITU in response to China’s attempt to influence international technical standards through initiatives such as New IP, which could reshape the fundamental architecture of the internet. The recent election of US candidate Doreen Bogdan-Martin to the position of ITU Secretary General and the UK’s election to the ITU Security Council are both victories. However, they are small wins and should not give rise to complacency.

China has successfully persuaded many developing countries to adopt its preferred infrastructure and technology by providing a combination of price and functionality not readily available elsewhere

China’s approach to technology governance resonates with many governments across the world, meaning that in the ITU – which operates on a ‘one country, one vote’ system – the UK and its traditional allies need to make a concerted effort to broaden their influence to include more middle-ground countries and those that are developing their technology ecosystems. Expanding partnerships multilaterally will require more UK and allied leadership at all levels, and in the case of the ITU, this will mean more representatives at the working level where standards negotiations take place.

When Should the UK Take Action?

While the realm of cyber policy is relatively new and constantly evolving, China’s intentions and aspirations have been clear for some time. A comprehensive approach for the UK in this realm is long overdue. China has successfully persuaded many developing countries to adopt its preferred infrastructure and technology by providing a combination of price and functionality not readily available elsewhere. This process has been formalised through the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), a programme initially outlined by President Xi Jinping in 2013. Earlier this summer, the G7 formally announced the $600 billion Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment (PGII), which aims to develop, expand and deploy secure information and communication technologies. However, it has been nearly a decade since China first announced and began implementing the BRI, and the UK and its allies have only just introduced a high-level intention.

The China challenge has been known for many years. What will it take to create the political will to force these disparate pieces to work together and be given the requisite resources that a challenge of this scale requires? The most likely answer at this point seems to be an external crisis of considerable magnitude. However, by the time such a crisis occurs, it may be too late to respond effectively. But hopefully, these rare interjections by UK intelligence chiefs underline the urgency of the China question and will be enough to kick our system into action.

The views expressed in this Commentary are the author’s, and do not represent those of RUSI or any other institution.

Have an idea for a Commentary you’d like to write for us? Send a short pitch to commentaries@rusi.org and we’ll get back to you if it fits into our research interests. Full guidelines for contributors can be found here.

WRITTEN BY

Julia Voo

- Jim McLeanMedia Relations Manager+44 (0)7917 373 069JimMc@rusi.org