A growing Western habit of linking China and Russia as joint adversaries in various contexts is missing the actual strengths of the relationship, and their varied interests in third locations.

Geopolitics have returned with a vengeance. Public discourse is increasingly conducted in adversarial terms, with ‘our side’ versus ‘their side’ dominating the strategic narrative. And while the ‘enemy of the day’ from a UK perspective is Iran, there is a growing discussion about China and Russia as though they are one and the same, a new ‘axis of evil’ working to stymie ‘our’ ability to operate in the world.

Reading between the lines of the narratives of most international confrontations, ‘they’ – for the most part the Russians and Chinese – inevitably appear to be supporting almost all of those who the UK (or ‘West’ more broadly) is against in the world: blocking votes at the UN; working together on military exercises; building up bases in the Arctic; and supporting Venezuela, Iran or the Syrian regime. This new entente appears to be behind many adversaries.

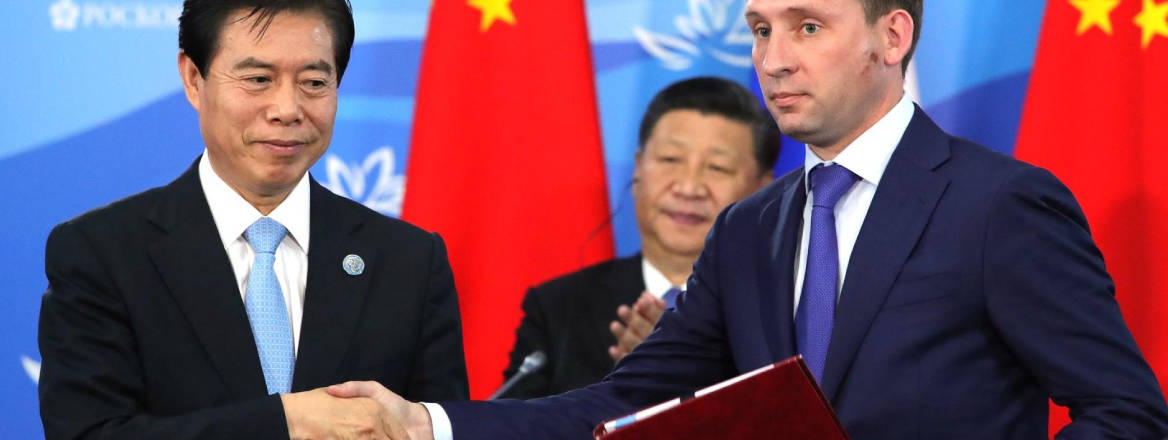

Yet there is a real danger of creating a Frankenstein’s monster in this interpretation of the Sino–Russian vector. There is no denying that the two have moved closer together in recent years – just watch the optics from Chinese Premier Li Keqiang’s visit to Moscow where he was feted as a great potential saviour of the Russian economy, or the latest security exercises involving Russian and Chinese forces, Tsentr 2019 – but the truth is that there are tensions between the two countries bubbling below the surface.

Start with Central Asia where there is a perennial tussle between the two over who is the dominant force. Russia has watched as China has become a major holder of regional debt, as its companies have moved in en masse to dominate local economies, and it is increasingly clear how China is moving into Russia’s traditional role of security provision. Chinese border guards are showing up along Tajikistan’s border with Afghanistan, doing training exercises and furnishing equipment. Security ministries across the region have growing numbers of officials who speak Mandarin or have experience in China. Russia’s power no longer looks as strong as it once was. It takes little effort to find voices in Moscow who worry about this erosion of Russia’s sphere of influence.

Or look at the growing Chinese technological penetration into Russia. Like much of the world, Russia is in the midst of a debate to determine who is going to build its 5G networks. But unlike the US, the UK or the rest of Europe, there is little evidence that Russians are going to resist China’s entry into this sector. Moscow’s spooks may worry about what this means for their dependencies on China but, as they will candidly say, what alternatives do they have? They point to who is sanctioning them at the moment. China may be scary, but the West is actually punishing Russia.

And, to look at a loftier normative level: China is fundamentally a status quo power, while Russia is the ultimate disruptor. Beijing quite liked the world structure as it was before US President Donald Trump took his sledgehammer to everything; the old world order fostered China’s stratospheric economic growth. It was a good path to which Beijing would like to return. By contrast, Russia has made itself increasingly relevant around the world through disruption, by creating chaos or by helping spur it along, as a prelude to Moscow inserting itself as an important player to help bring resolution.

These are fundamentally contradictory positions: Beijing likes the status quo, while Moscow derives relevance in chaos. And there are moments where these two perspectives have clashed. Beijing disapproved of Moscow’s redrawing of Ukraine’s borders (and Georgia’s beforehand). China has its own provinces with ethnic minorities seeking independence and recognition. It certainly does not like the precedents that Moscow set in recognising the South Ossetians and Abkhazians in Georgia or the breakaway parts of Ukraine. What if people were to start doing this to Tibet or Xinjiang?

Yet notwithstanding these tensions, the West is increasingly looking for a China–Russia axis around the world. The US has articulated this axis most clearly in the Pentagon’s National Defence Strategy, and similar concerns are echoed in Brussels and London. More glib commentary tries to separate them out – Russia is described as being a storm, while China is climate change. The argument here is that both are problematic, only that the former is an irritant, while the other is seismic. Yet increasingly such perspectives consider the two countries as parts of a linked problem.

Russia and China are not blind to this narrative and the broader global confrontations. For them it can be useful to show a strong alliance in the face of the growing Western bloc. At most major international conferences, senior figures stand up and champion their close relationship. They are undertaking ever more ambitious and important military exercises together. Beijing’s strategic bombers have participated in Russia alongside 1,600 troops as part of the massive Tsentr 2019 military exercise, the third or fourth such drill this year they have done together. They are talking about an ‘Ice Silk Road’ over the Arctic and have obviously developed a modus vivendi of sorts over what is going on in Central Asia. Li Keqiang’s latest visit has highlighted more investments into Russia (and Russian sales to China), at a time when Beijing’s economy continues to suffer under US trade tariff impositions.

Beijing and Moscow also share a worry about the ongoing pattern of popular uprising endangering regimes around the world. For Beijing this is most visible in Hong Kong, while Moscow has watched protestors rumbling on its streets for some time. For both of them, the fear is that this is part of the bigger wave of ‘colour revolutions’ that swept through Georgia, Ukraine and Kyrgyzstan in the 2000s, and more recently through the Middle East in the Arab uprising. Seeing these as Western-orchestrated plots to bring down governments the West found inconvenient, Moscow and Beijing worry that they might be next on the list.

There is no doubt that China and Russia increasingly see their futures as linked and are binding themselves closer together. But the West’s current habit of only seeing them this way is exacerbating this tendency and creating a unified adversary.

Adopting such an approach also means the UK is blind to the potential opportunities that exist on the ground in some contested areas of the world. Simply seeing a China–Russia axis means that observers miss their different equities in different places, and the fact that the local dynamics in each context and region vary. The UK must be careful not to will itself into a confrontation against an adversary that does not always exist.

The views expressed in this Commentary are the author's, and do not represent those of RUSI or any other institution.

WRITTEN BY

Raffaello Pantucci

RUSI Senior Associate Fellow, International Security