Criticism of the UK’s Rwanda Policy Misrepresents African Agency

While much of the controversy around the UK–Rwanda partnership is understandable, African perspectives are too often missing from the debate.

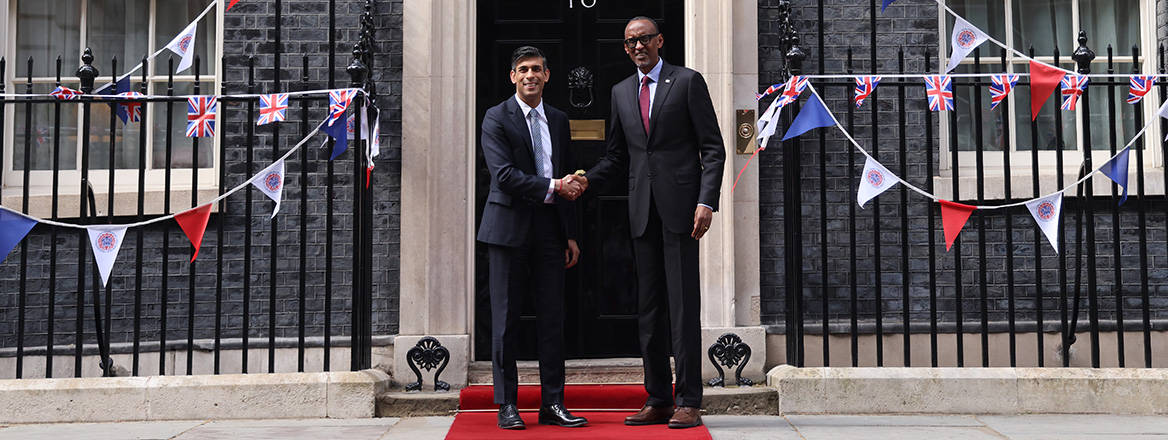

In April 2022, Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s Conservative government launched one of the most controversial policy initiatives in recent UK history, announcing that unwanted arrivals would be relocated to Rwanda as part of an effort to stop small boat crossings of the English Channel.

Analysis of this policy has been almost solely framed by UK perspectives. The furore among UK civil society, opposition parties and talking heads is understandable, and in many ways justified. Beneath much of this criticism, however, is also a damaging subtext. In their quest to criticise the government and the partnership, many critics consistently draw on negative stereotypes of Africa. In a more subtle way, these critics employ the same framework of otherness and orientalism that they so indignantly condemn when it is used by anti-immigration campaigners.

This rhetoric frames Africa as a dangerous, hostile environment, and Rwanda as a country wholly subservient to the West and beholden to its handouts. It betrays a white saviour mentality which is inherently racist and presupposes African inferiority. In this case, Rwanda is cast as a recipient rather than a participant in the partnership. Whenever Rwanda’s agency is discussed, it is assumed that the country is simply in it for the money and is being twisted to do the UK’s dirty work.

The reality in Africa, however, is different. Facts about Rwanda, in particular, speak for themselves. The 2022 World Justice Project Rule of Law Index, for instance, shows that Rwanda leads Africa in several areas, ranking 42nd globally on the rule of law overall, as well as 27th on ‘Order and Security’, 24th on ‘Equal Treatment and Absence of Discrimination’, and 34th on ‘Absence on Corruption’. Rwanda is in so many ways a standout – a secure, innovative, modern country which is making rapid progress in almost every sphere.

While Rwanda is not perfect, its track record in many areas is often ignored, as are the wider contexts of its domestic and foreign policy initiatives

This shouldn’t be news to anyone. Over the last two decades, Rwanda has been one of the world’s fastest growing economies, carving out its own unique path – promoting innovation, technology and people-centred solutions across a variety of sectors. The Rwanda Green Fund, for instance – Africa’s first national environment and climate change investment fund – helps the government to mobilise finance from the international community and the private sector to fund climate resilience, emissions reduction and green jobs. Rwanda has pioneered smart cities to provide clean urban environments. The country has its very own space agency, which recently launched the 'Icyerekezo' satellite to provide high-speed internet to the isolated island of Nkombo on Lake Kivu. Its collaboration with Starlink and SpaceX expands on these efforts, aiming to provide high-speed internet access to under-served areas across the country.

Rwanda’s innovative initiatives go beyond its own borders. For instance, it was one of the world’s first countries to ban single-use plastics, and it is using this experience to lead international efforts against plastic pollution, starting with the co-sponsoring (with Peru) of a historic resolution at the UN Environment Assembly 5.2. In geopolitical terms, Rwanda punches further above its weight than any other country on peacekeeping, supplying the highest number of UN peacekeepers per capita – not to mention its bilateral arrangement with Mozambique to quell the Islamist insurgency in Cabo Delgado. Most recently, it has also led African efforts to bring vaccine production to the continent, spurred by the injustice and hoarding seen during the Covid-19 pandemic. In February, BioNTech opened its first African manufacturing facility in Kigali, which will soon be able to produce around 50 million doses a year.

None of this is to say that Rwanda is perfect, of course. It has had well-documented challenges. Yet Rwanda’s track record in many areas is totally ignored, as are the wider contexts of Rwanda’s domestic and foreign policy initiatives – obscured by deeper preconceptions of ‘Africa’. This is a two-sided partnership, where Rwanda has just as much agency as the UK. Seen in this context, new dimensions of the partnership are revealed.

Rwanda’s vision for combatting migration is for greater investment in the African continent, and greater opportunities in secure locations for migrants. It wants to break the current status quo that benefits absolutely nobody: not the migrants themselves, who risk their lives only to be treated as second-class citizens in Europe; not African countries, who are losing out on young, talented people who can put an end to their ‘brain drains’; and not European countries, where refugees are seen by some as a dangerous political threat. Rwanda is far from a dumping ground – it is a pragmatic, innovative and forward-looking actor.

Why do we remain fixated on sticking-plaster solutions at the end of the refugee journey, rather than investing in preventing these outflows at the source, or empowering ‘first responders’?

In the European imaginary, there is only room for a single story about Africa: one of a desperate wasteland filled with the starving children spotlighted by NGO and charity advertisements, which Africans seek to escape by cramming themselves into dinghies and ‘invading’ European shores. The real-world damage of this is stark. In 2021, for instance, when the Omicron Covid-19 variant was detected by South African laboratories, the backlash against the continent was severe. Within days, blanket flight bans devastated Covid-affected African economies, while racist images – including cartoons depicting Omicron as an invasion of black Africans on small boats – were spread widely. Africans are not, of course, the only group to suffer from such discrimination. Polarising and sensationalised issues like immigration often produce a corrosive ‘us vs them’ mentality, which can radically transform stereotypes. Eastern Europeans, for instance, have long occupied an uncomfortable space within the Northwest European racial imaginary, which has often been a spark for political controversy. Africans find it harder than most, however, to shake off these misconceptions.

It is little wonder, in this context, that Western audiences find it hard to grapple with Africa’s ability to be part of the solution. Yet this is madness precisely because, as the Rwandan approach recognises, both the crisis and its solutions originate in Africa. Just as the continent produces many of the world’s refugees, it also hosts the vast majority of them. Uganda and Kenya, for instance, both now hold record numbers of refugees, and bear a significantly greater burden than countries like the UK, Greece or Italy do. Why, then, do we remain fixated on sticking-plaster solutions at the end of the refugee journey, rather than investing in preventing these outflows at the source, or empowering ‘first responders’? In part, this failure stems from a lack of faith in the ability of African actors to effect meaningful change.

We cannot allow these misrepresentations of the agency of countries in Africa and the Global South to persist. Instead, we must redefine the narrative. Particularly when we speak of global issues like migration, climate change or pandemics, we must focus on the ability of Africa and the rest of the Global South to make meaningful contributions and to lead international efforts. We are all ultimately in the same boat in this globalised world. A change in mindset, therefore, is not just an option – it is a necessity.

The views expressed in this Commentary are the author’s, and do not represent those of RUSI or any other institution.

Have an idea for a Commentary you’d like to write for us? Send a short pitch to commentaries@rusi.org and we’ll get back to you if it fits into our research interests. Full guidelines for contributors can be found here.

WRITTEN BY

Dr Andrew E. Yaw Tchie

Senior Research Fellow at the Training for Peace Programme

- Jim McLeanMedia Relations Manager+44 (0)7917 373 069JimMc@rusi.org