Rickety Anchor: North Korea Calls its Illicit Shipping Fleet Home amid Coronavirus Fears

North Korea appears to have ordered a significant portion of its shipping fleet to return home in what is likely a reaction to the global outbreak of the coronavirus, new analysis by Project Sandstone can reveal.

Using Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) and optical satellite imagery, analysis by Project Sandstone shows that North Korea’s main ports contain an unprecedented number of vessels usually engaged in moving North Korea’s waterborne trade in and out of the country.

The trend, which began in the middle of February 2020 as coronavirus took hold, put an end to the large and coordinated efforts to evade United Nations Security Council (UNSC) resolutions by shipping resources to China as tracked by Project Sandstone – a RUSI initiative to systematically analyse and expose North Korean proliferation and illicit shipping networks – and publicised in its latest report, ‘The Phantom Fleet: North Korea’s Smugglers in Chinese Waters’. The discovery also reinforces analysis by NK News – a US-based information website – which shows very limited activity at the country’s border crossings and cargo facilities.

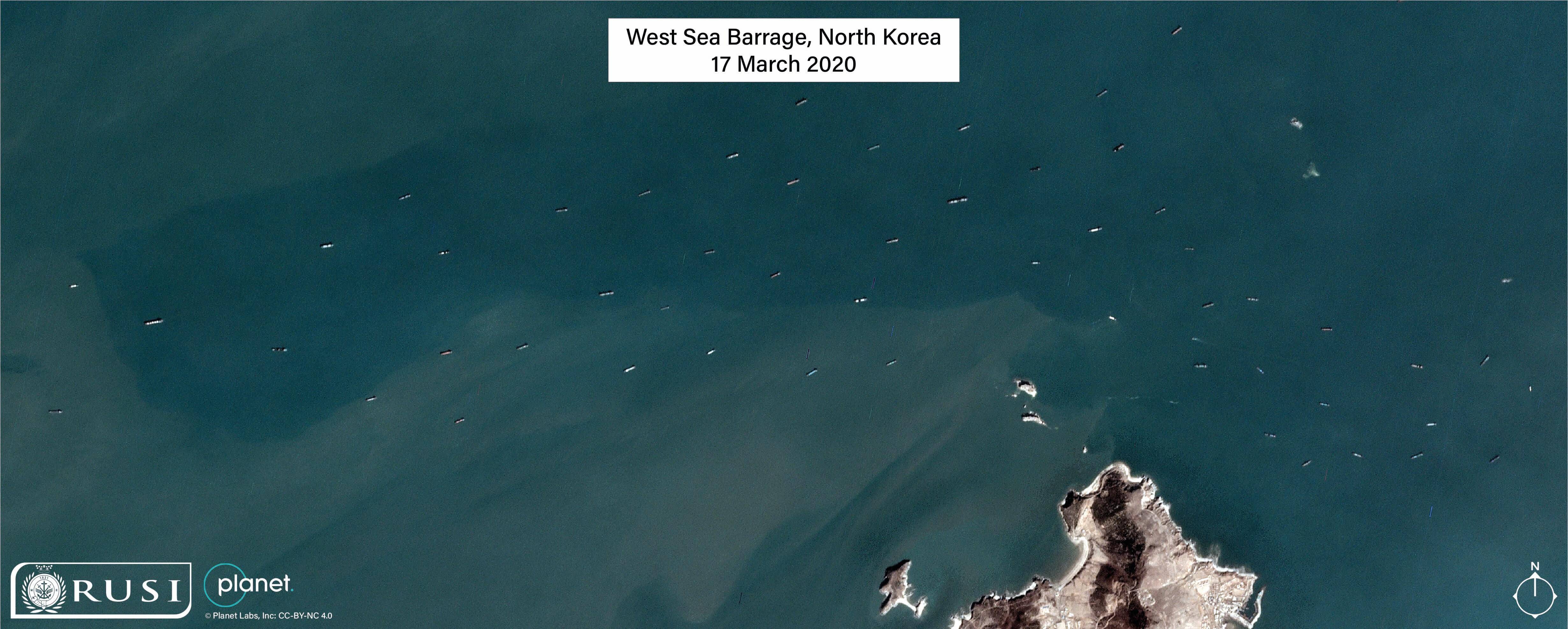

Figure 1: Dozens of Vessels Outside the West Sea Barrage, North Korea, 17 March 2020.

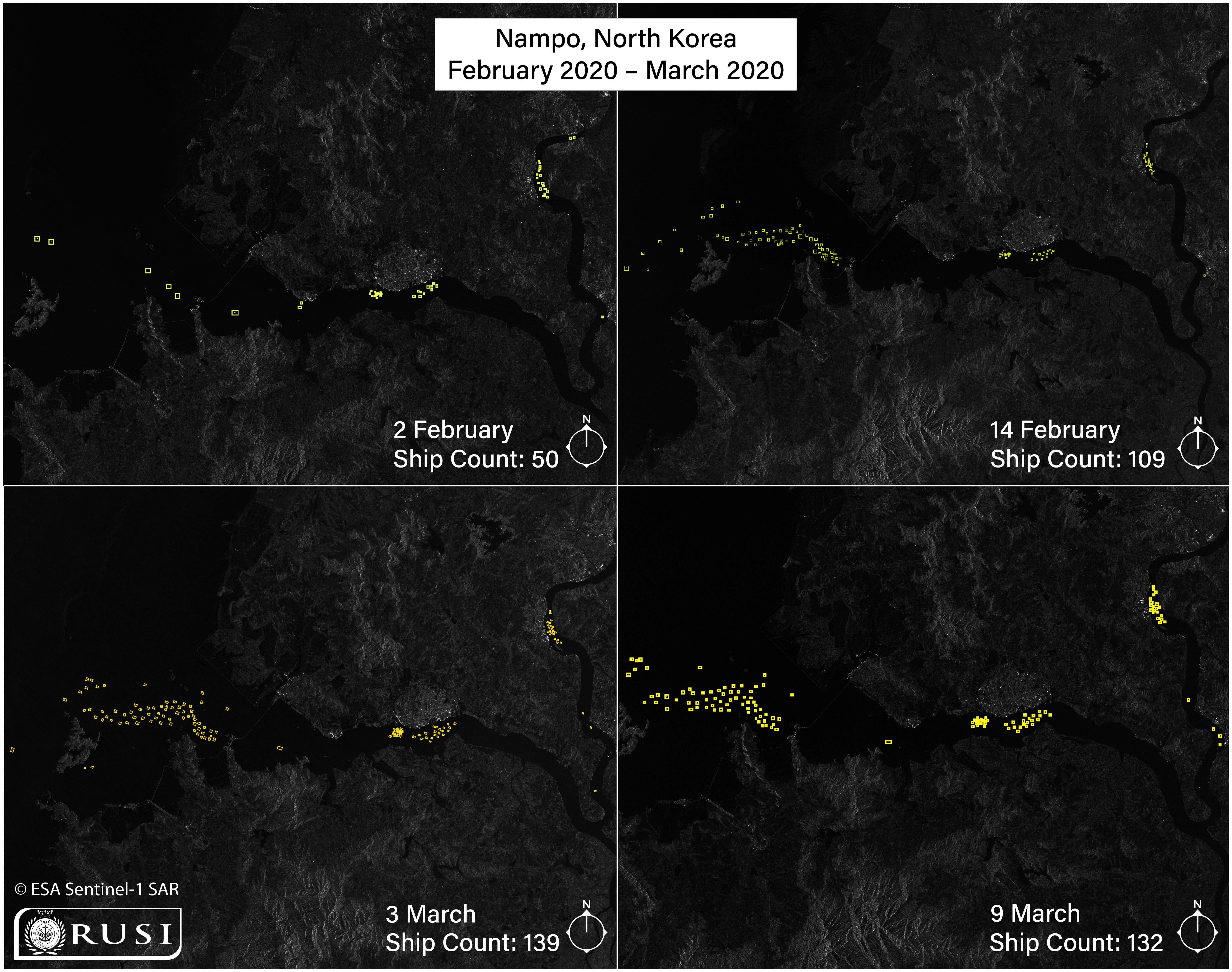

Project Sandstone’s latest report revealed industrial-scale sanctions breaches occurring in Chinese waters throughout 2019 and into early 2020. However, satellite imagery collected and analysed by Project Sandstone since January 2020 shows a large number of the vessels previously engaged in this illicit activity now anchored in North Korean ports as journeys to Chinese territorial waters dwindled.

Among them are dozens of other North Korean ships, including a number of sanctioned cargo vessels, bulk carriers and oil tankers crucial to keeping the country’s economy afloat, as well as supplies and revenue flowing to the military and other important institutions. In fact, recent images taken across February and March show over a hundred motionless vessels anchored in the same areas – an unprecedented phenomenon in North Korea’s otherwise bustling port area of Nampo.

Real Fragilities

While North Korea has continued to test missiles during this global pandemic in a purported display of confidence, the recalling of its fleet is a signal of Pyongyang’s real vulnerabilities.

Figure 2: North Korean Vessels Return Home in Increasing Numbers, Nampo, North Korea, February–March 2020.

With limited air connections, sealed borders to the south and only a small number of crossings on its northern frontier with China, North Korea relies heavily on its merchant fleet to move goods and commodities in and out of the country. The discovery, therefore, raises significant questions about the resilience of North Korea’s already fragile economy and what impacts the cessation of this trade will have on the country’s ability to generate funds for imports such as petrol, diesel and equipment for the nuclear and ballistic missile programmes.

While North Korea appears to have been able to effectively circumvent some multilateral and unilateral sanctions measures seeking to arrest this trade – albeit at significant costs – the recall of its shipping fleet has put an abrupt stop to the country’s ability to export coal, iron ore and other natural resources by sea. These commodities are effectively the mainstay of Pyongyang’s illicit export portfolio and are used to fund strategically important sectors and institutions.

Without these resources, which are sold abroad in US dollars or Chinese renminbi, North Korea has increasingly limited means to pay for necessary imports, the flow of which is also likely to face severe disruptions as a result of the anchoring of the fleet and potential closing of its land borders.

Although it is unknown whether North Korea has the necessary financial reserves to weather the crisis, the multilateral and unilateral sanctions regimes imposed on the country mean it is unable to adopt the same monetary or fiscal measures deployed elsewhere to issue government debt and tap liquid capital markets.

Meanwhile, dollar or other denominated currency reserves it holds illicitly abroad may be of little use to Pyongyang as it has moved to close the borders and anchor the fleet. Neither is it clear if North Korea holds significant volumes of strategic oil storage, other petroleum stockpiles or the facilities to effectively store and refrigerate any perishables imported for the elite in Pyongyang. A 2017 research paper by the US-based Nautilus Institute estimated that the armed forces accounted for 31% of total oil and petroleum use, and that the country potentially had up to a year’s worth of stockpiles for routine usage.

Virus Vulnerabilities and Societal Implications

While many countries across Europe and Asia have been hit hard by the coronavirus outbreak, North Korea is also highly vulnerable to the virus given the chronically poor condition of the country’s healthcare infrastructure.

The UN in-country humanitarian team details ongoing concerns about a lack of adequate medicines, laboratory consumables and medical equipment as well as competency of health care providers. It estimates that just over a third of the country’s 25 million citizens are in immediate need of support in this sector. The UN also estimates a similar number of North Koreans remain in need of the most basic support in the areas of water, sanitation and hygiene services, critical to limiting the spread of diseases.

Pervasive illnesses such as tuberculosis also remain a significant public health issue for North Koreans, with the UN announcing around 90,000 new cases detected in 2018 alone. coronavirus therefore could be especially devastating to average North Koreans already impacted heavily by such long-standing medical issues and a lack of government support.

The central government, aware of these factors, reacted rapidly to the outbreak of the virus by shutting its borders, as it has done previously in response to other viral outbreaks, such as SARS in 2003.

North Korea media first reported on the coronavirus epidemic in China on 22 January, the same day that Hubei province launched a Class 2 Response to Public Health Emergency. North Korea reportedly closed off its borders to tourists on the same day.

Several days later North Korean media announced that the country had switched its anti-epidemic system to an emergency one which reportedly involves the tightening of sanitary and quarantine inspection at border areas, ports and airports and the isolation of travellers suspected of carrying the virus. Domestic measures put in place included a mandatory 30-day quarantine for anyone entering the country as well as measures imposed at its major port in Nampo designed to limit the exposure and spread of the virus via ships and personnel travelling from overseas.

In fact, it is at Nampo where the vast majority of the recalled vessels are congregated.

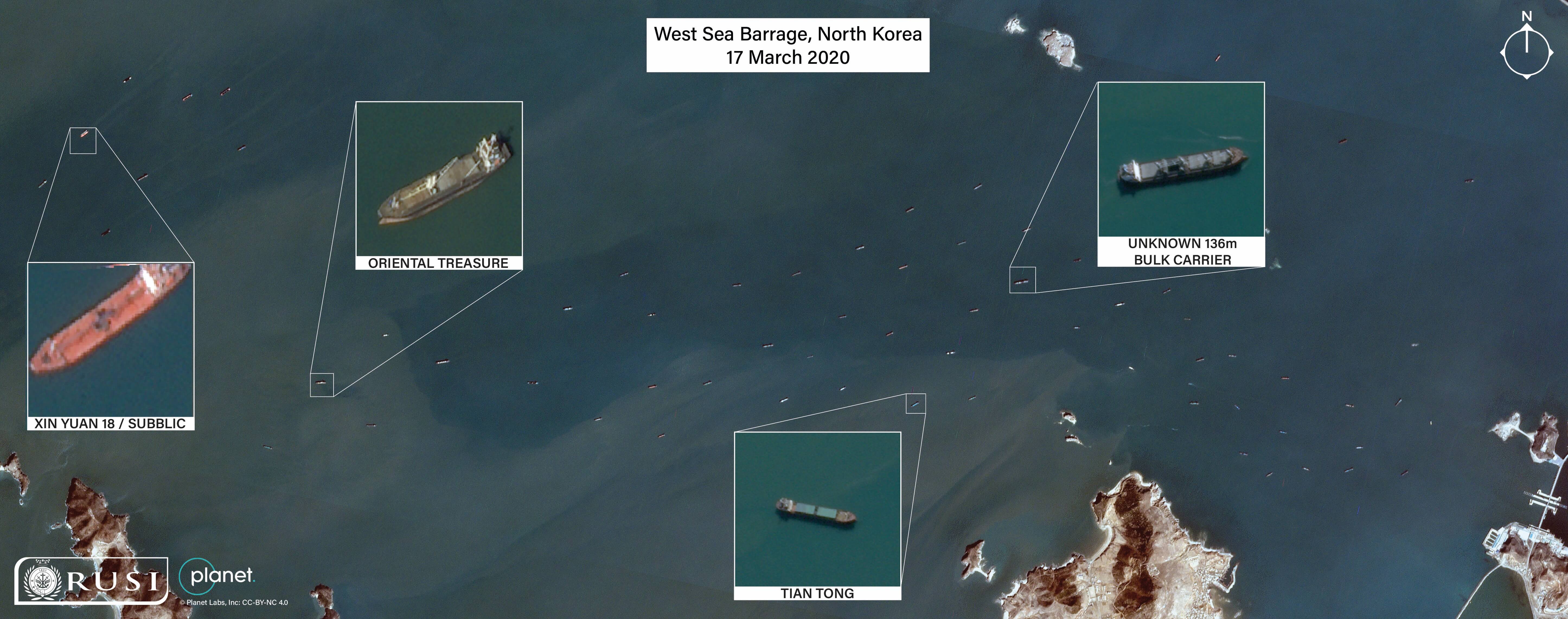

Figure 3: North Korea’s Cargo Ships Anchored Outside the West Sea Barrage, West Sea Barrage, North Korea, 17 March 2020.

Incidental Implementation

What is significant about the apparent recall, however, is that many of the ships present in the imagery have been dispatched abroad over the last few years with the task of breaking UUNSC sanctions imposed against the country in response to its continued development of its Weapons of Mass Destruction (WMD) programme.

Among these are dozens of vessels previously tracked by Project Sandstone throughout 2019 and early 2020 as they ventured into Chinese territorial waters, such as the Ka Rim Chon, Tae Pyong� and the Boun 1. Meanwhile, some of North Korea’s most active and scrutinized oil tankers are also present, including the UNSC designated Sam Jong 2 and New Regent. The Vifine, a foreign flagged vessel recently enlisted into North Korean oil smuggling operations, is also present in the imagery.

Figure 4: North Korean Vessels Anchored off Nampo, North Korea, 13 March 2020.

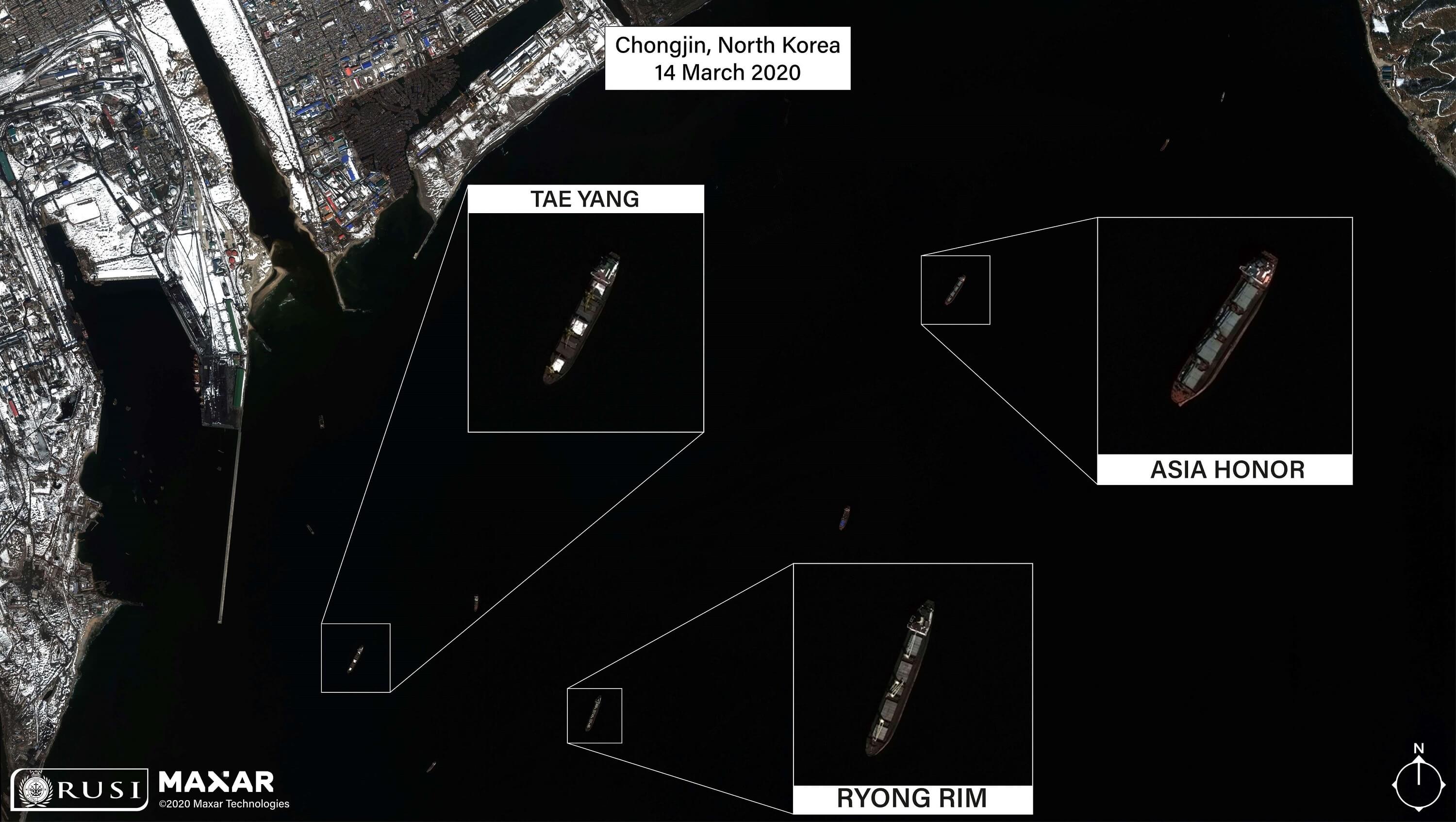

While Nampo represents the primary port where this phenomenon has occurred, Project Sandstone has seen similar groupings of the North Korean vessels in Chongjin, where some of North Korea’s largest cargo ships are now anchored including the Tae Yang, Asia Honor and the UNSC designated Ryong Rim.

Figure 5: Several North Korean Bulk Carriers in Chongjin, North Korea, 14 March 2020.

Although optical and SAR imagery shows many of these vessels have been stationary for long periods, it remains unclear if the crews remain quarantined onboard the vessels. Recent imagery taken by Planet Labs on 24 March 2020 shows that a large cluster of vessels anchored outside the West Sea Barrage have moved, indicating the crews may have remained onboard.

The anchoring of North Korea’s shipping fleet may have long-lasting ramifications for the country’s economy and has immediate consequences for Pyongyang’s ongoing efforts to evade UNSC resolutions. Furthermore, with China reporting no new domestic cases of coronavirus and North Korea recording no cases of infection, the ongoing anchoring of the country’s shipping fleet may provide an important insight into Pyongyang’s risk calculations as the crisis unfolds.

The views expressed in this Commentary are the authors', and do not represent those of RUSI or any other institution.