On 15 May 1957, Britain tested its first hydrogen bomb as part of the first Grapple series of tests.

Although quickly hailed as a success, the test’s actual disappointing yield was withheld until 1993. Was this a premeditated lie as part of a ‘thermonuclear bluff’? New archival research has revealed that the public claim that the 15 May Grapple test was in the ‘megaton range’ was generated out of a premature rush to celebrate unconfirmed results rather than deliberate intent. With this information, a more complete picture can now be presented of how daunting expectations undermined the considerable technical advancements in Britain’s first hydrogen bomb test.

It must be understood that the Conservative governments of the 1950s were under great pressure to produce ‘megaton range’ nuclear devices. National prestige was an important factor behind the 1954 decision to acquire hydrogen bombs, only further emphasised after the October 1956 Suez Crisis. Thermonuclear weapons were seen as offering the potential to save on defence: Duncan Sandy’s April 1957 Defence White Paper placed a greater emphasis on nuclear weapons at the expense of conventional forces. In 1956, Anthony Eden had announced Britain’s intent to test ‘megaton range’ thermonuclear weapons with the Grapple tests, thereby setting a benchmark for success. By 1957, Harold Macmillan was conducting public diplomacy on disarmament with the Soviet Union via letters exchanged with the Soviet Minister of Defence—if Britain were to develop a credible nuclear deterrent, all necessary testing would have to be concluded before the imposition of an atmospheric testing moratorium, which if agreed between the US and USSR, would make it politically untenable for the UK to continue. Britain also sought to restart nuclear weapons development cooperation with America through demonstrating its own accomplishments (when this was achieved in 1958, Macmillan hailed it as ‘the great prize’). Therefore Britain’s future defence policy, participation in international disarmament negotiations and national standing were perceived to hinge on its hydrogen bomb programme.

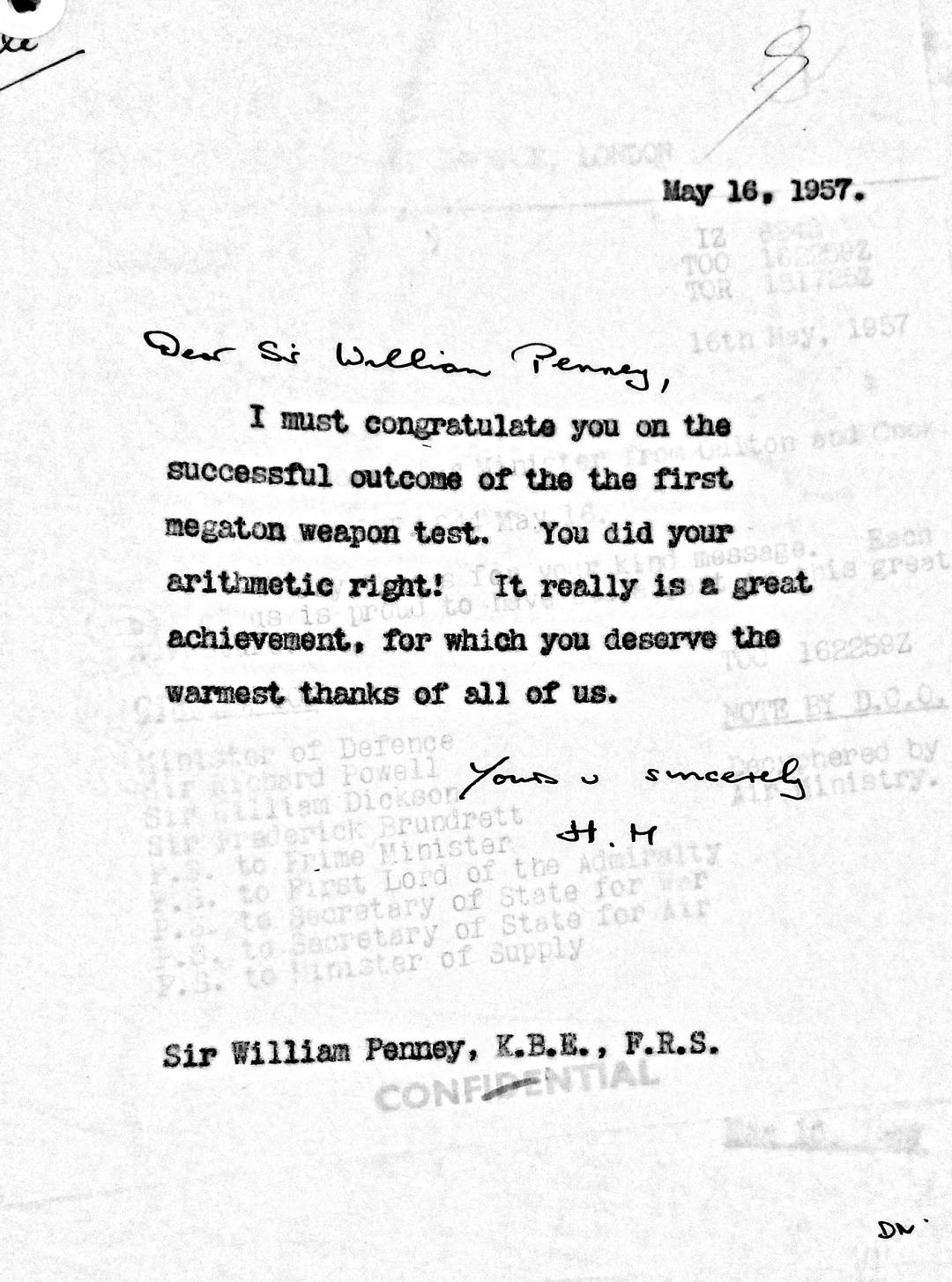

With national prestige at stake, it is unsurprising that the 15 May test results were prematurely celebrated when initially reported back from the South Pacific as 0.5 megatons. Despite it taking time to fully analyse collected samples to determine yield accurately, Harold Macmillan hastily wrote to William Penney, AWRE director and father of the British bomb, congratulating him ‘on the successful outcome of the the [sic] first megaton weapon test.’

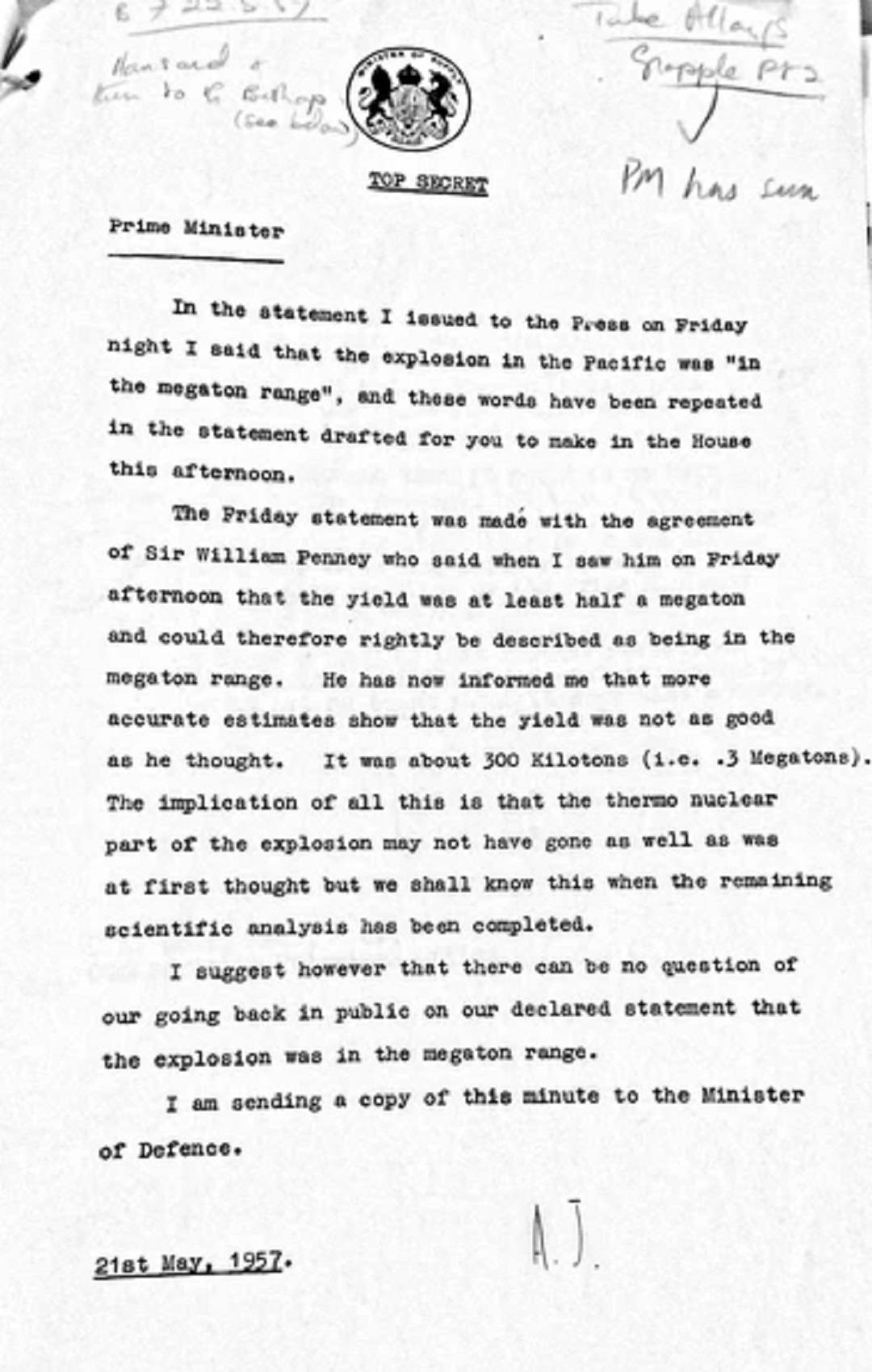

On 17 May, the Minister of Supply, Aubrey Jones, briefed the press that preliminary results were ‘in the megaton range.’ By 20 May, however, London had been informed that rather than the 0.5 megaton yield initially predicted, the true result was closer to 0.3 megatons – therefore not in the ‘megaton range’.

A document dated 21 May 1957 reveals that Aubrey Jones advised that ‘there can be no question of our going back in public on our declared statement that the explosion was in the megaton range.’ The Prime Minister’s statement to the House on the same day notably avoided making any discussion of “the precise yield” due to ‘reasons of national security.’ From the summer of 1957 onwards, the true yields of Britain’s Grapple nuclear tests became matters of ‘the highest possible security classification‘ to avoid the embarrassment becoming public.

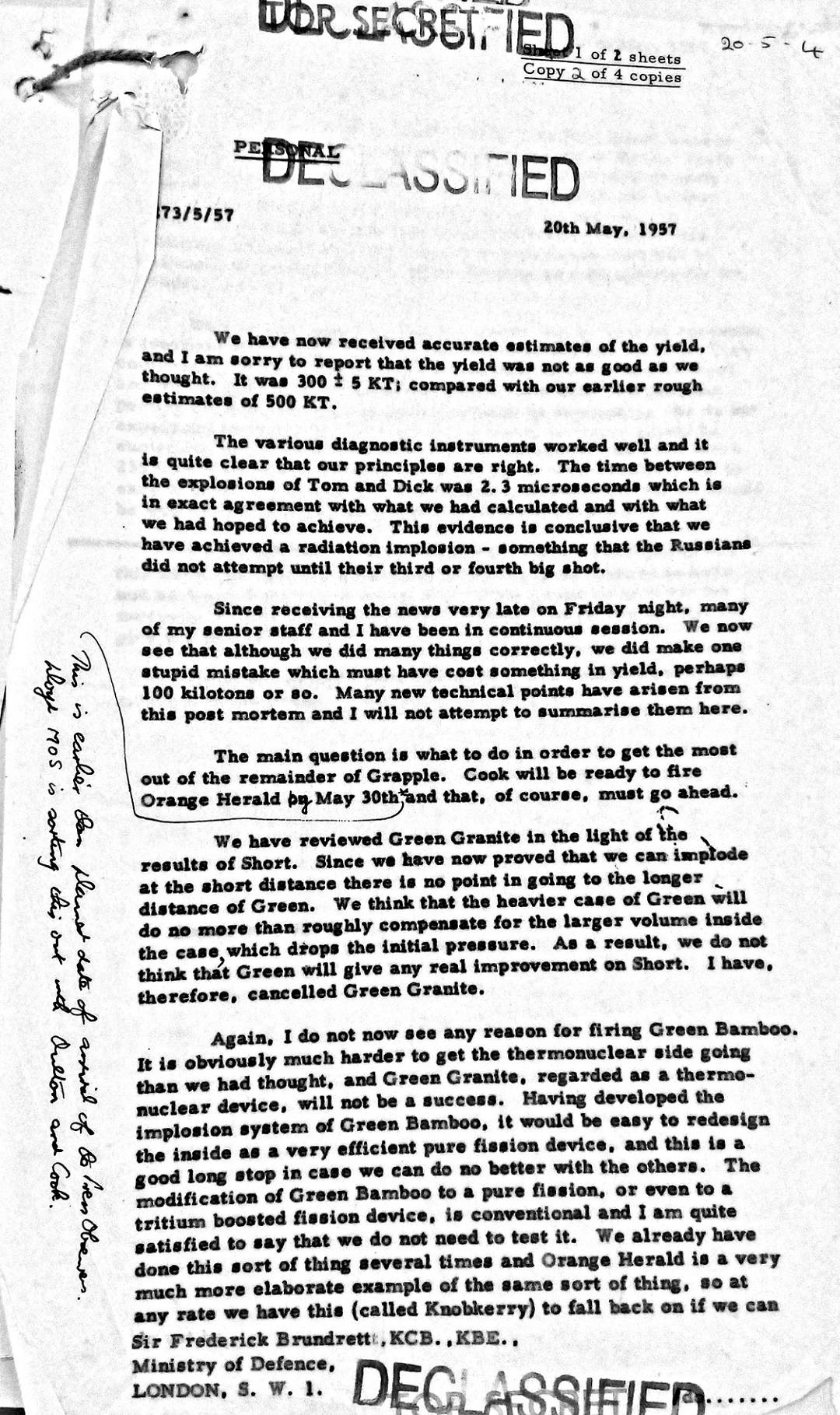

From a purely technical perspective, the first Grapple test on 15 May 1957 was reasonably successful as it suggested that British weaponeers were on the right track: although the yield was lower than expected, radiation implosion produced the majority of the device’s energy. William Penney, highlighted this achievement and noted that this wasn’t attained by the Russians ‘until their third or fourth big shot.’ Penney believed that the yield had been lowered by ‘one stupid mistake which must have cost something in yield, perhaps 100 kilotons or so.’ Unfortunately for AWRE, attempts to rectify flaws in their design were unsuccessful and a follow up test on 19 June 1957 produced an even smaller yield. Nevertheless, the technical lessons learnt contributed to the subsequently successful Grapple X, Y and Z tests which produced definitively ‘megaton range’ thermonuclear yields. Had the political embarrassment surrounding the test been avoided, AWRE would likely have more openly celebrated the test as a true technical (if incomplete) achievement.

While the configuration and relative yields of nuclear devices may seem like an arcane and academic debate, it continues in the present day. Although North Korea has claimed that its 2017 nuclear test was ‘thermonuclear,’ it has been suggested that this may be a partial bluff. When national prestige and deterrence are tied to the perception of nuclear testing success, lies – accidental or otherwise–are not out of the question.

Geoffrey Chapman is a PhD candidate and research assistant at the Centre for Science and Security Studies at King’s College London. His thesis is on the institutional development of Britain’s nuclear weapons programme and he writes on other CBRN issues.

Image Credit: Dutch National Archives, The Hague, Fotocollectie Algemeen Nederlands Persbureau (ANEFO), 1945-1989

Document 1: PRO AB 16/2439 Penney to Brundrett – 20th May 1957

Document 2: PRO PREM 11/2857 Macmillan to Penney – 16th May 1957

Document 3: PRO PREM 11/2857 Jones to Macmillan – 21st May 1957