An Integration Model for the North Caucasus: Culture and Discourse

Integrating the North Caucasus with the rest of Russia is a delicate balancing act between encouraging homogeneity and recognising cultural distinctiveness.

Moscow has gradually implemented a strategy that aims to integrate the North Caucasus with the rest of Russia after decades of violence and instability that have weakened the ties between them. Creating a new political and economic system is at the core of this policy. But there are other dimensions. Vladimir Putin said in 2010 that ‘the North Caucasus has to be fully integrated into informational and humanitarian space of our country. Federal TV and radio channels shall provide more content about the region’.

The North Caucasus (Chechnya, Dagestan, Ingushetia, Kabardino-Balkaria, Karachay-Cherkessia, Stavropol Region and the Northern Ossetia-Alania) and Russia have a deep historical relationship. Since the mid-1990s, the dominant narrative associates the region with violence and terrorism. In addition, integration efforts are impacted by region’s diversity and complexity in terms of cultural norms, traditions, languages, ethnicity, and historical events that have shaped collective memories.

This article investigates the current integration model for the North Caucasus, which is being implemented by national and regional authorities. Building on expert interviews with Yevgeny Ivanov, Marat Iliyasov and six other anonymous experts, it analyses what elements of this model should be prioritised or amended to ensure sustainable regional peace and prosperity.

This paper offers the following findings. First, public discourse on the region requires repairing and balancing, changing negative associations no longer reflective of the situation on the ground, and showcasing successful local projects related to development. Storytelling about the region should educate the Russian audience about the complexity and diversity, emphasising its drive to develop. Second, to ensure accommodation of diverse nationalities within a unified Russian society, two lines of efforts should be reinforced: support and promotion both minority languages and cultures and Russian language and culture to foster the integration.

Integration Model for the North Caucasus?

An integration model is a set of state policies that promote regional peace and development, and aim to link a region into broader political, legal, economic, social, cultural and discursive spaces. While political, legal and economic policies provide a foundation for sustainable peace and integration, narratives, discourses and the promotion of unifying socio-cultural identities – while accommodating linguistic, ethnic, religious distinctiveness – are crucial in shaping the perception of belonging. Experts note that more work needs to be done in that regard as there is still a lack of acknowledgement that the North Caucasus is composed of very diverse regions and needs targeted treatment according to the local dynamics of its constituent elements. Such diversity makes it very challenging to formulate an integrated approach.

Discourse and Perception

The two Chechen wars and subsequent political violence shaped the public perception of the North Caucasus for decades. Labelling violent groups operating in the North Caucasus as ‘gangs’, ‘criminals’, and especially ‘terrorists’, contributed to the construction of public support for their elimination. Due to the violence and its presentation in the media, the North Caucasus became a place of permanent instability in the public and media perceptions. But the transition from conflict to peace requires narratives suitable for peacetime and the reduction of the negative residual impact of hostile narratives remaining from active armed combat.

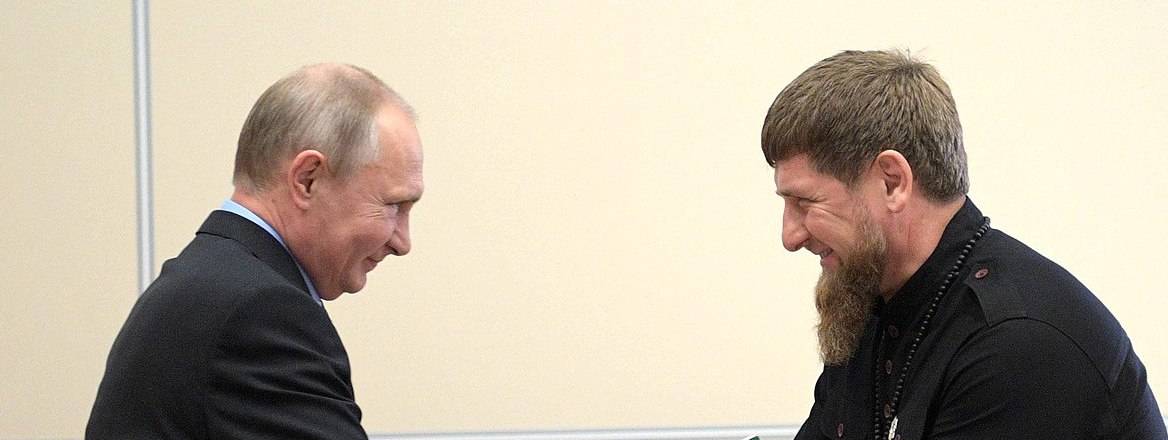

A current counternarrative deployed by both the federal centre and the regional elite focuses on the unity of the North Caucasus and the rest of Russia. Chechnya, as a former separatist republic, has been placed at the heart of that discourse. Aimed at a federal audience, Ramzan Kadyrov, the Chechen leader since 2007, has repeatedly stated his loyalty to Russia, emphasising the willingness of the Chechens to live in Russia and linking the prosperity of the republic to a strong and stable Russian state. Regime survival in Chechnya requires keeping the federal government satisfied while making clear that the Chechen nation reached its objectives by staying in the federation. Aimed at a Chechen audience, Kadyrov has articulated his foremost loyalty to Chechnya. These narratives negotiate between compliance with Russian demands and Chechen autonomy. However, communication at the elite level is not reflective of views in the general population – it merely showcases the current official discourse.

Changing views of the region among the Russian population will inevitably challenge deep-rooted stereotypes. Residents of the North Caucasus travelling to other Russian regions are still viewed as strangers and often face similar attitudes to those expressed towards migrants from Central Asia. Furthermore, xenophobia and Islamophobia can exacerbate anti-Caucasian sentiments.

Experts suggest that the media should report more on successful stories from the North Caucasus, ‘stories of those people who live in the Caucasian context but are educated, mobile and modern’. It is vital to mitigate levels of public anxiety about the region in order to integrate it. Drawing public eyes towards stories of innovative local businesses, tourist projects, fashion brands, art galleries, and other local successes is one way to serve this cause.

Culture and Language

‘The North Caucasus is a major centre of diverse but united Russian spiritual culture. Any attempts to break this unity have always met with resistance, including from the Caucasus peoples themselves. The people of Russia and the peoples of the Caucasus share a common destiny’, said Putin in 2004. Building (at least in discourse) a common cultural space was important in the years following the war, as it still is now. Notions of ‘Historic Russia’, or of a ‘Russian cultural code’ promote Russia as multinational society but united nation. The formula of ‘diversity but unity’ suggested by Putin seems the only possible model to accommodate the great variety of ethnic groups, languages, religions, traditions and beliefs coexisting in the North Caucasus.

Diversity can potentially drive economic growth, but it can also cause confrontation. Regional distinctiveness can be embodied in a cultural clash between ‘the Caucasian’ and ‘the Russian’. This clash has manifested itself in the perception in Russian cities that North Caucasian migrants behave in ‘uncivilised’ ways. Ethnic enclaves in cities reinforces this perception. These perceptions are partially reflected in the police practice of ‘stop-and-searching’ people who look ‘Caucasian’.

This culture clash is also evident in certain historical celebrations like those on 23 February or 8 March. While the rest of Russia celebrates 23 February as Defender of the Fatherland Day and 8 March as International Women's Day, in the North Caucasus these dates mark the anniversary of the tragic deportations of the Vainakh and Balkar peoples.

However, this discrepancy was settled between the federal centre and regional elites. For example, in Chechnya, 23 February is now celebrated as Defender of the Fatherland Day (as everywhere in Russia), while the Deportation Day was moved to 10 May (also a day of commemoration for Akhmad Kadyrov, the father of the current regional leader, who was assassinated on 9 May 2004). Moving the commemoration of deportations to other dates is a very sensitive issue in the North Caucasus. There is also a reverse trend of commemorating regional resistance to the Russian rule, exemplified by Kadyrov’s opening of the Dadi-Yurt Memorial in Chechnya. To an extent, commemorating historical events selectively or shaping collective memories in an politically acceptable manner demonstrates the loyalty of regional elites to Moscow.

The issue of languages is also sensitive. Russian is the lingua franca in the region, and necessary for keeping social unity. The latest amendments to the Russian Constitution restated the special place of the Russian language. In Article 68 (1), the Russian language is secured as the language of ‘a state-forming nation which is a part of the union of equal nations of the Russian Federation’. This phrasing should not be considered an attempt to undermine other languages. In fact, Article 68 (2) reiterates that the national republics retain the rights to use their own national languages along with the Russian language.

Noteworthy amendments to the law on education, adopted in 2018, concerned the issue of national (native) languages. Russian citizens have the right to be educated in their national (native) language and study languages from the list of national languages. The amendments secured the freedom to choose one’s language of education and to study a national language. It is important to note that the availability of languages education is determined by the capacity of the Russian education system. In practice it means that the options for language learning are limited by the capacity of educational institutions. Experts believe that such amendments indirectly impact the future role of national languages in national republics: less demand from parents for their children to be either educated in or study a national language will result in less supply due to less allocated funding – a full class of students studying a specific national language receives higher institutional support than one student interested in a subject. Thus, national languages may be excluded from higher education.

Approaches to teaching national languages varies within the national republics. In Chechnya, both Russian and Chechen are state languages that are embedded in the education system. After the adoption of the amendments, Kadyrov assured the public that the Chechen language would be preserved. In his view, those interested in learning national languages have no obstacles to do so and added ‘a Chechen who does not want to study the native language regardless of one’s residence is not a Chechen’. Keeping demand and supply for national languages in monoethnic republics like Chechnya – where Chechens constitute 95% of population – might differ significantly from other regions with a more diverse ethnic and linguistic composition.

The promotion of national languages in Russia needs state support but also public interest in the republics. State support includes building space for the media to operate in national languages, or local authorities to communicate in native language along with Russian – for example, key Chechen officials often speak publicly in the Chechen language. Federal support is also exemplified by the establishment of the ‘Foundation for the Preservation and Study of the Native Languages of the Peoples of the Russian Federation’ in 2018, which is tasked with the production of textbooks to study national languages and support authors publishing in national languages. This is an ambitious mission as Russia has over 250 languages and dialects, 58 languages used in education, and 36 languages with a status of state languages in 22 regions. Dagestan alone has 32 languages. To preserve its linguistic plurality, Dagestan combines top-down activities under the republic’s Ministry of National Policy and Religion and bottom-up initiatives, such as creating applications to study national languages and audio books in national languages.

Experts suggest that the preservation and promotion of local cultures and languages, however superficial it might look, is extremely important for Russia and the North Caucasus. Especially in such republics with such a conflictual past as Chechnya where accommodating distinct local cultures, traditions and languages aids peacebuilding. At the same time, the promotion of Russian culture and language is a key feature of integration.

Conclusion

Integration constitutes a balancing act between unification and the preservation of uniqueness. The preservation of regional complexity and distinctiveness contributes to building regional strength and competitiveness, for example, in economic development and tourism. Integrating means overcoming an existing mental border between the North Caucasus and the rest of Russia. But regional individuality should not be channelled exclusively through cultural traditions. The region can modernise and develop while preserving regional identities. Promoting integration narratives requires targeted policies from Moscow and the participation of local authorities, private stakeholders and civil society in the North Caucasus.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s, and do not represent those of RUSI, the OSCE Academy in Bishkek or any other institution. This paper was prepared in cooperation with RUSI and the Friedrich Ebert Foundation in the framework of Remote Russia Visiting Fellowship.