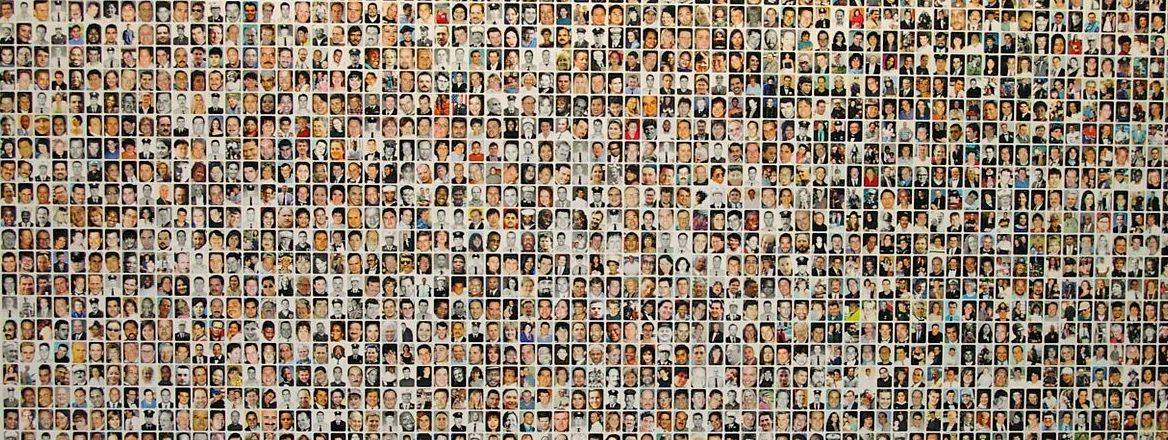

Two Decades After 9/11, Let Us Not Forget This is About People

Policies, military strategies and capabilities, and partnerships have all been constant themes in the debate on the 20 years of counterterrorism since 9/11. But the harrowing footage from Afghanistan has once again put the human aspect of terrorism in the spotlight.

Above all else, terrorism and counterterrorism are about people: the people conducting the attacks and their victims, and the people trying to stop the attacks. Two decades after 9/11, it is hard to find a family in the UK that has not been touched by the War on Terror in some way: the size of the armed forces has varied between 150,000 and 200,000 personnel for the past 20 years, so a not insignificant portion of the population will have family members or friends with direct experience of the conflicts in Afghanistan and Iraq. Many living in Muslim communities will have other perspectives; one of the awful consequences in the West of the 9/11 attacks and the response to them has been the creation, or the perception, of difference based on religion and culture which did not exist in the same way before. This has changed how people identify themselves within communities and how they relate to others in extremely complex ways. And, of course, the victims of terrorist attacks and their families are the hardest hit.

In the case of the terrorists, we often do not see them until they conduct their attacks. The priority has been, rightly, to find them and stop them from committing terrorism, and there have been some remarkable and critical successes. But the focus on finding them means we have spent 20 years being more concerned about where they are than who they are. Even now, we know very little about the people in leadership positions in Islamist terrorist organisations. For example, Saif Al-‘Adl, the approximately 58-year-old Egyptian deputy leader of Al-Qa’ida, has been in Iran for most of the last 20 years. We are told he is a pragmatist who operates with ruthless efficiency. What do we really know about what he is thinking? What do we know about what his wife is thinking? Who are his rivals? What really annoys him? What kind of conversations does he hold with his Iranian ‘hosts’? What kind of conversations is he having with the leaders of the Taliban with whom he built relationships in the 1990s? A deeper understanding would take us beyond sweeping commentary on Salafi-Jihadism and present instead an organisation with leaders and members, each with their own life stories, ideals, commitment and ambitions. If we knew more about the people we are fighting, we would be able to have a more thoughtful conversation about what to do next.

This is, of course, almost impossible because they are hiding from us, and therein lies the challenge. We face a serious practical problem of how to understand what is happening on the ground. Who to talk to? Who to trust? We fall back on data analysis: location information, telephone numbers and email addresses. President Joe Biden’s ‘over-the-horizon capability’ will struggle to get beyond names and data; will be vulnerable to misinformation, prejudice and manipulation; and will miss opportunities to ask people why they are fighting against the West, to build an understanding which would inform better foreign policy decisions. If we really want to know our adversaries, then we need to build networks which reach directly to them: we have to get personal.

We might ask, for example, why we are supposed to be reassured when the older generation of the Taliban are reportedly restraining the younger, more extreme, members of the group; why people are leaving the Taliban to join Islamic State Khorasan Province; or why the same seems to be happening in Nigeria. Could it be the case that after 20 years of fighting, the lines have hardened on each side?

It is also incumbent on us not to make assumptions about the choices women will make. Many Afghan women are devastated by the return of the Taliban. Although it is harder to demonstrate (and will make for uncomfortable reading), some women support the Taliban. We should not assume that a woman is less capable of choosing to support a terrorist group, or of choosing an extreme way of life, than a man is. We see much less of their activity in support of terrorist groups but that does not mean that it is not there, or that they are carrying it out as victims of oppression. One of the incidents leading to the siege of the Red Mosque (Lal Masjid) in Islamabad in 2007 was the kidnapping of three Chinese women accused of running a brothel by female students from the Jamia Hafsa – a madrassa for women with more than 6,000 students. Its principal, Umme Hassan, is still agitating. On 20 August 2021, the Jamia Hafsa briefly erected the Taliban flag in the centre of Islamabad, before being made to take it down. Videos of female students singing ‘Salam Taliban’ to celebrate the Taliban takeover are available on social media. We need properly to understand why women might choose an extreme form of Islam, taking on the life of a Mujahida – and that means finding a way to hear from them without sensationalising it.

How Should We Tell Our Story? Who Tells Our Story?

9/11 is becoming history. How will we remember it? We are at the point where we should be thinking about how we turn a contemporary event into a historical one which is understood in all its chaos and nuance by later generations of our diverse societies. We need to create space for thought about what we tell ourselves about this shattering event in our historical narrative. Those who memorialise our history – in particular, national museums and historians – have a vital and urgent role to play. No child at school today was born when 9/11 happened, and nor were most of today’s undergraduates.

Despite its clear impact on the world, 9/11 is not included as part of the national curriculum in England. Teachers face a difficult issue of how and whether to teach it. It might be included in citizenship, religious education, art, English and drama, or it might not. The topic is not in the history curriculum, and with schools juggling competing pressures to update historical narratives, it is easy to see how it might be overlooked, or perhaps just be too difficult to teach. And yet children’s lives have been shaped by it, even down to its impact on other aspects of their curriculum. They will hear about it from friends and family, who will have their own very diverse opinions and experiences. They will be watching the news from Afghanistan, Syria, Iraq or parts of Africa, and wondering what on earth is going on. It is particularly difficult to work out how to teach about campaigns which have not gone well, but it is doubly important, because the repercussions shape not only our own societies but how others perceive us, and the fortunes of our adversaries.

The views expressed in this Commentary are the author’s, and do not represent those of RUSI or any other institution.

Have an idea for a Commentary you’d like to write for us? Send a short pitch to commentaries@rusi.org and we’ll get back to you if it fits into our research interests. Full guidelines for contributors can be found here.

Related content

WRITTEN BY

Suzanne Raine

RUSI Trustee