Syria, Captagon and Geopolitics: From Magic Bullet to Placebo

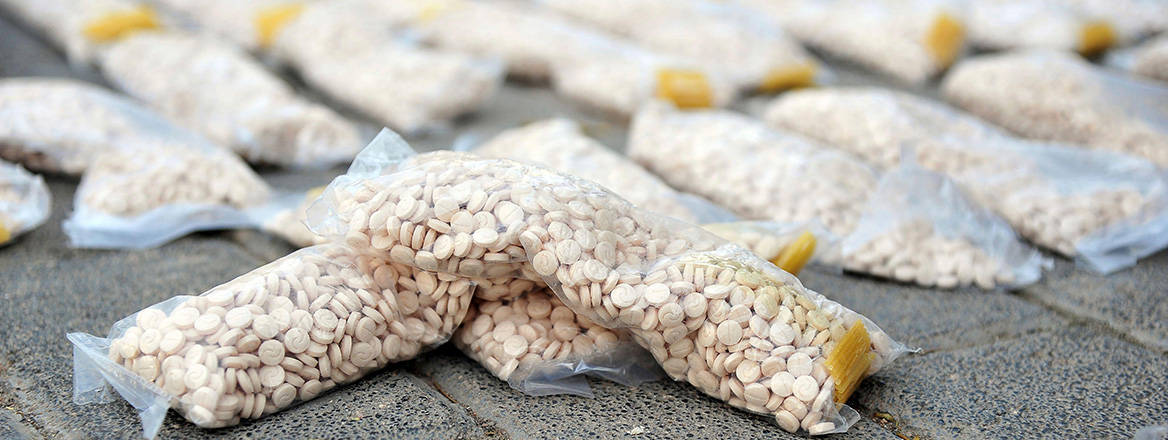

Since its emergence in the early years of the Syrian Civil War, ‘Captagon’, a cheap amphetamine, has had a seismic impact on both the societies and geopolitics of the Middle East.

In May 2023, Syrian President Bashar al-Assad appeared in Riyadh at the annual Arab League summit for the first time since Syria’s suspension in November 2011. A sea change was afoot in the geopolitics of the Middle East: China had brokered a deal between Iran and Saudi Arabia in March, and key Arab League members were eyeing the restoration of Syria’s seat at the table, setting a clear distance from the position of the US. Resettlement of millions of internally displaced persons and refugees, aid to the earthquake-afflicted northwest, and the lifting of UN sanctions all figured in the vote to readmit Assad into the Arab League. But Assad’s promise to ‘stem the flow’ of Captagon, an easy-to-produce pill at the centre of an estimated $10 billion dollar trade, received particular interest.

Further investigation into the 2020 seizure of 84 million Captagon pills (worth an estimated €1 billion) from the Italian port of Salerno confirmed to Western observers what Arab journalists and Middle East policy specialists had long known: that the Assad regime was the major player in the production and export of the amphetamine from Syria. From regime-aligned actors to members of Assad’s close family, the regime and its network of allies have, according to the Syrian Observatory of Political and Economic Networks, direct control over approximately $7.3 billion of Captagon revenues. In their historic decision to reintegrate Syria, regional powers judged Assad, as Captagon’s largest beneficiary, to be best placed to rein in the trade. Many regional commentators therefore held the curtailment of Captagon to be a ‘strong tool’ wagered by Assad to win over the wealthy Gulf states, at once securing reconstruction funds, avoiding concessions to the Syrian opposition and regaining long sought-after international legitimacy.

More than a year on from normalisation, and the trade in Captagon has shown few signs of slowing down. Much-vaunted interdictions and the removal of several sanctioned individuals connected to the Captagon trade in Syria and Lebanon have done little to obscure the reality that Captagon production and trafficking from Syria (and the concomitant flow of cash into the coffers of the Assad regime) has continued unabated. Promises to ‘stem the flow’ have, thus far, produced little in the way of results.

Captagon, Within Syria and Without

Captagon is the name commonly given to the stimulant Fenethylline, which was first synthesised and sold as an anti-narcolepsy medication in Germany in the early 1960s, until it was banned in the 1980s for its harmful side-effects.

The reality is that the Assad regime has little interest in losing the income and benefits afforded to its patronage network by Captagon

For most of its illicit life, Captagon has been endemic to the Eastern Mediterranean: through the 1990s and early 2000s, Captagon was illicitly produced, trafficked and consumed in the Balkans and Turkey, and by the mid-2000s the Hezbollah-controlled Bekaa Valley – long a nucleus of cannabis and opium production – had become the centre of Captagon production too. After Hezbollah’s decision to enter the Syrian Civil War on the side of Assad in 2013, Captagon production facilities began moving to regime strongholds on the Alawite Coast and in the Qalamoun Mountains.

Though Captagon use was reported among many of the parties in the Syrian Civil War, Assad-aligned entities such as the Fourth Armoured Division, the Military Intelligence Directorate and the National Defence Forces emerged as the largest actors involved in the production, distribution and trafficking of Captagon within Syria. This entered a newly intensified phase after the regime, with help from Russia and Iran, retook the Daraa, Suwayda and Quneitra governorates in southern Syria from the Free Syrian Army (FSA) in 2018. The Captagon network expanded to accommodate fragile alliances with local strongmen, who could operate within kinship networks that straddled both Syria and Jordan. For extant drug traffickers, this represented a green light from the regime to smuggle Captagon over the border and on to the lucrative markets of the Gulf. Sanctioned individuals such as Amer Khiti exemplified the versatile illicit actors commonly involved (Khiti began his career as a livestock trader), whose enterprises expanded following regime affiliation.

Changing Course

The Jordanian experience, in particular, highlights the connection between the illicit trade in Captagon and changes to regional geopolitics. In recent years, Jordan has been through cycles of disengagement and direct cooperation with the Assad regime, standing as it does at the forefront of regional drug control efforts.

Sharing a nearly 400-kilometre border with Syria, Jordan’s border security and civil society have been particularly hard-hit by Captagon inflows from Syria. Between 2020 and 2023, the Jordanian army foiled over 1,700 smuggling and infiltration attempts, from gangs storming the border on foot to trucks filled with furniture and agricultural goods used to conceal the pills. Meanwhile, Captagon consumption has surged across all strata of Jordanian society. As one researcher puts it, Captagon is used by everyone from ‘average workers to archaeologists’. The consumption of hashish and crystal meth, both of which have been found in Captagon shipments, has also risen in conjunction with Captagon use.

In light of these developments, Jordan helped lead the push for the normalisation of relations between the Arab League and Syria. Calls between Assad and Jordan’s King Abdullah III as early as 2021 showed signs of a thaw in a relationship that had been frozen throughout the Syrian Civil War.

Despite steps towards normalisation in 2021, 2022 saw the persistence of large-scale Captagon smuggling into Jordan. Faced with, according to a Jordanian Colonel, an increasing presence of ‘armed groups alongside the traffickers’, Jordan’s military adopted a ‘shoot-to-kill policy’, instated after a Jordanian army captain was killed in an ambush by Captagon smugglers in 2021. This hair-triggered policy has led to significant skirmishes, such as one in which 27 smugglers were killed in January 2022.

Jordan’s kinetic approach is tied into its hostile relations with actors over its Syrian and Lebanese borders. An investigation by the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project found that Hezbollah and Maher Al-Assad’s Fourth Armoured Division were responsible for the escort of drug traffickers and the supply of increasingly advanced military hardware for use in cross-border smuggling. Importantly, these developments continued to escalate despite Jordan’s attempts at diplomacy. A heavy-handed approach to Captagon is now the norm, as further evidenced by the Jordanian airstrike on the home of suspected smuggler Marai al-Ramthan.

The Gulf monarchies have also been eager to demonstrate a hardline approach to Captagon. But according to present estimates, net inflows of the drug have not meaningfully changed since normalisation with Syria. In Saudi Arabia, which accounts for approximately 50% of global Captagon consumption, mass seizures have continued since May 2023 – although, unlike Jordan, there is very limited public information on total estimated net inflows, and little understanding of the associated impact on public health.

A Bleak Prognosis

Over a year on from Syria’s re-entry into the Arab League, the notion of Captagon control as a credible tool in Assad’s aspirations for regional legitimacy has fared poorly in the face of a meagre crackdown on the harmful trade. The reality is that the Assad regime has little interest in losing the income and benefits afforded to its patronage network by Captagon. Crucially, for the Assad regime to deprive itself of its main source of income in the interests of complying with the demands of the international community would part with a logic that has served it through years of authoritarian rule: make minimal concessions, sit tight, and wait until the flack dies down. For now, reengagement is ongoing ‘despite’ the continuation of the trade, but it is unclear whether this will last.

Though Syria may continue to float commitments and promises of action, its continued track record risks undermining what little trust exists with neighbouring and regional states

Apart from the clear disincentive for Assad to limit a multi-billion-dollar trade several times larger than all of Syria’s annual exports combined, there are questions as to the regime’s capacity to reduce Captagon outflows. Attempts to dismantle Captagon production and smuggling in contested areas of southern and northeastern Syria may present existential risks to a regime heavily reliant on a tenuous patronage network of local militias and Bedouin clans. Many of these actors are former FSA fighters or are closely aligned with Iran, whose pervasive influence in Syria has extended to altering the country’s confessional mix. In neutralising these elements, the Assad regime would have to assert its authority over actors whose loyalties lie with Tehran as much as with Damascus. Moreover, in the event of a reduction in Syrian-produced Captagon, displacement back to Lebanon’s Bekaa Valley or Iraq’s Anbar province could maintain the drug’s supply to destination countries.

The theoretical risks of a crackdown are yet to be substantiated, largely due to a lack of meaningful action by the Syrian regime against Captagon. What is becoming abundantly clear, however, is that promises to cut the regime’s financial life support have represented a placebo rather than a magic bullet for the Arab League’s Captagon disease. Though Syria may continue to float commitments and promises of action, its continued track record risks undermining what little trust exists with neighbouring and regional states. Questions therefore abound over the current and future policy responses that Syria’s neighbours and international partners will adopt in an effort to address Captagon flows – with or without Syria.

The views expressed in this Commentary are the authors’, and do not represent those of RUSI or any other institution.

Have an idea for a Commentary you’d like to write for us? Send a short pitch to commentaries@rusi.org and we’ll get back to you if it fits into our research interests. Full guidelines for contributors can be found here.

WRITTEN BY

Elijah Glantz

Research Fellow

Organised Crime and Policing

George Hancock

Former RUSI Course Assistant

- Jim McLeanMedia Relations Manager+44 (0)7917 373 069JimMc@rusi.org