Russia–North Korea WMD Cooperation: New Challenges of an Old Partnership

While the recently signed agreement between Russia and North Korea has sparked concern in the West, the reality is that cooperation between Moscow and Pyongyang on sensitive technologies is not new – it is merely coming out into the open.

Russian President Vladimir Putin's recent visit to Pyongyang and the signing of the Russian-North Korean bilateral agreement on mutual military assistance, as many observers have already pointed out, was intended to send a clear signal about Russia's willingness to expand its cooperation with one of the world’s most toxic regimes, and one that poses a threat to the West. Supporting such regimes, as well as transferring sensitive military technologies to them, is intended by the Kremlin to demonstrate Russia's readiness for further escalation with the West in the event of the latter’s continued support for Ukraine. It is obvious that the leadership of Russia is not ready for such an escalation and wants to avoid a direct military confrontation with NATO and its allies, but it is not against pushing others to participate in such a conflict. First Deputy Secretary of the Security Council and ex-President Dmitry Medvedev, who since the beginning of the Russian invasion has been used to voice the most explicit threats against the West, stated before Putin's visit to North Korea the need to arm parties fighting with NATO at the same time as organising social destabilisation in Western countries and waging economic war against them, including by damaging critical infrastructure.

There is no doubt that among the potential candidates to be used for confrontation with the West, North Korea is in one of the leading examples, alongside terrorist organisations, with whom it would be inappropriate even for Russia to sign such agreements. Putin's strategy here is quite clear: to raise the stakes, threatening to undermine stability in regions where the US has security obligations (not just in the Indo-Pacific region, but also in the Middle East and the Balkans), and to force the US into separate negotiations on the Ukrainian issue on conditions that are beneficial to Russia. In addition, the desired result is the unleashing of new wars on the periphery of US interests, diverting attention and resources from Ukraine and continuing to weaken the West.

The West has demonstrated the expected level of public concern, including regarding possible Russian support for North Korea's missile programme. This is exactly the kind of reaction the Kremlin was counting on when the signing of the agreement with North Korea was being planned. The official rapprochement between Russia and North Korea is certainly something that should be taken seriously, but it is necessary to understand that technological assistance to Pyongyang has been provided by Moscow before – long before Russia had public grievances with the West over the latter’s support for Ukraine, and even when Russia still officially supported UN sanctions against North Korea.

It is believed that North Korea's modern missile programme was the product of technological and financial assistance from unknown countries. However, the analysis of samples of North Korean missiles, which fell into the hands of the Institute of Armaments and Military Equipment of the Ministry of Defense of Ukraine in connection with the beginning of their use by Russia in the war against Ukraine, indicates that a significant proportion of the missile technologies of North Korea are of Russian origin. For example, the North Korean solid-fuel tactical ballistic missile KN-23 (Hwasong-11Ga) – – which Pyongyang received in 2018, is remarkably similar to the Russian Iskander-M missile, has a maximum range of 690 km, and can be used with both conventional and nuclear warheads. Russia has been using these missiles against Ukraine since at least December 2023 – at least 24 cases of the use of such missiles in Ukraine are known.

The Russian origin of the technologies used in the production of KN-23 missiles is indicated by the following:

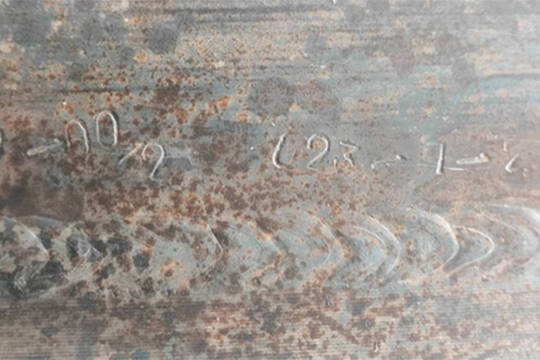

- In the production of the KN-23 missile cruise engine (Image 1), Russian rotary hood technology is used, which is indicated by the annular grooves (Image 2).

2. All markings that are placed on individual elements of the KN-23 missile are made in accordance with Russian standards, in particular the ‘Unified system of design documentation’, GOST 2.113-75 ‘Group and basic design documents’ (Image 3).

3. Analysis of the chemical composition of the materials from which the rocket elements are made indicates their Russian origin. The body of the fuel tank of the marching engine is made from Russian steel of the type 12X2NVFA, 19X2NVFA, 21X2NVFA and 23X2NVFA, and the rocket's gas-dynamic rudders are made from Russian grade 9 tungsten alloy, which is actively used in Russian industry.

There is nothing surprising in this information, even if it might appear sensational at first glance. From its very foundation, North Korea DPRK received constant assistance from the Soviet Union in the production of weapons, military equipment and nuclear technology. Thus, the North Korean Hwasong-5 tactical ballistic missile with a flight range of 330 km and the Hwasong-7 medium-range missile are both modified versions of the Soviet R-17 missile, which was part of the Elbrus missile complex, and the KN-02 Toksa missile is a modification of the Soviet short-range ballistic missile ‘Tochka-U’. The Yongbyon Nuclear Research Center, which produces the material used in North Korean nuclear weapons tests, was established with the help of the Soviet Union and equipped with a Soviet IRT-2000 nuclear reactor.

The official transfer of samples and technical documentation for these missiles to North Korea by Egypt and Syria is only a cover, since these countries are only operators of these missiles and have never been able to produce them on their own. Moreover, when in the 1990s and 2000s North Korea actively supplied ballistic missiles of its own production for export, among the buyers – along with Iran, Pakistan, the UAE, Libya and Yemen – were Syria and Egypt. At the same time, in the mid-1990s, North Korea entered into an agreement with the Russian Makeyev State Rocket Center, part of Roscosmos, to design a ‘launch rocket for space launches’. The Soviet nuclear ballistic missile R-27, which was placed on submarines, was taken as a model. To carry out these works, a group of Russian specialists was sent to North Korea. After 2010, as a result of this cooperation, North Korea received the Hwasong-10 ballistic missile, also known as Musudan, with a range of up to 3,500 km.

The greatest threat to international security is Russia's interest in opening new theatres of military operations with the participation of other authoritarian regimes

The position of the Russian leadership regarding cooperation with North Korea in this area was also not particularly hidden. One of the first foreign visits made by Putin after his election in 2000 was to North Korea, where a cooperation agreement was signed. In 2001, during a visit by then- leader of North Korea Kim Jong-il to Russia, Putin signed a joint declaration with him that ‘the North Korean missile programme is peaceful and does not threaten countries that respect the sovereignty of [North Korea]’. Despite the fact that Russia joined the UN Security Council sanctions against North Korea in 2010, this did not affect the level of relations between the countries. In 2011, during another visit by Kim Jong-il to Russia, his meeting with then-Russian President Dmitry Medvedev took place on the territory of the Russian military base of Sosnovy Bor in Ulan-Ude, where at that time there were still significant stocks of chemical weapons. In 2014, North Korea became one of 11 countries that recognised the legality of the Russian occupation of Ukrainian Crimea. In the same year, a bilateral agreement was signed to cancel all North Korean debts to Russia (at that time amounting to about $10 billion).

The facts of Russia's support for North Korea’s missile and nuclear programmes in violation of UN Security Council resolutions are also well known. Thus, the US government applied sanctions against a number of Russian companies and citizens who have participated in it. In particular, at the beginning of 2022, the State Department imposed sanctions against two Russian companies – Parsek LLC and its head Roman Alar, and Apollon LLC and its director Aleksandr Gayevoy – for activities that supported the North Korean WMD programme and its means of delivery. Of course, in the tightly controlled Russian system, such activities could not be carried out without the knowledge and participation of government organisations.

It is obvious that Russia's cooperation with other authoritarian regimes is not a consequence of the deterioration of its relations with the West, but a natural phenomenon that Russia used to hide better, and the West chose not to notice. What is new in this cooperation is the strengthening of Russia's dependence on it. Russia's critical dependence on the supply of weapons, and in the foreseeable future probably troops from these countries, will in turn make Moscow much more willing to share sensitive technologies with them. At the same time, the greatest threat to international security is Russia's interest in opening new theatres of military operations with the participation of other authoritarian regimes, which would both disperse the resources of the Western coalition and consolidate the ‘new axis of evil’. The opening of such new theatres could be the result of provocations by the Russian intelligence services, in which the transfer of technologies necessary for developing WMD is only one of the possible triggers.

The views expressed in this Commentary are the author’s, and do not represent those of RUSI or any other institution.

Have an idea for a Commentary you’d like to write for us? Send a short pitch to commentaries@rusi.org and we’ll get back to you if it fits into our research interests. Full guidelines for contributors can be found here.

WRITTEN BY

Oleksandr V Danylyuk

RUSI Associate Fellow, Military Sciences

- Jim McLeanMedia Relations Manager+44 (0)7917 373 069JimMc@rusi.org