Russia and Ukraine: ‘One People’ as Putin Claims?

As Russia’s military threats to Ukraine intensify, it is worth dissecting President Putin’s use of historical props to justify the claim that Russia and Ukraine are one nation.

In July, Russian President Vladimir Putin published an extraordinary essay denying Ukraine’s independent history, an argument amplified in a later Q&A. Former President Dmitry Medvedev followed this up with an open letter, using undiplomatic language to brand Ukrainians as ‘people who do not have any stable self-identification’, ‘prey to rabid nationalist forces’, and ‘absolutely dependent people’. ‘It makes no sense for us to deal with these vassals’, Medvedev concluded.

Putin currently works in isolation because of the coronavirus pandemic. Yet he is apparently having historical files delivered so he can 'study' the Ukrainian question more, indicating that there may be even more essays to come. The whole topic is clearly a personal idée fixe for him: back in July 2013, and before the annexation of Crimea and the war in eastern Ukraine that followed during the subsequent year, he gave a speech in Kyiv stating that all of Ukraine was historical Russia.

Historical ‘Shortcuts’

Putin employs three characteristic sleights-of-hand. First, he constantly switches terminology, by defining everyone as ‘Russian’. This is just playing with language; it is not a real argument. Second, Putin ignores what happened when Ukrainians and Russians lived in separate states – actually for a longer period than when they lived together. Third, he constantly asserts the existence of a common language and religion, which is simply not the case. The Russian Orthodox Church exists in Ukraine, as the Ukrainian Orthodox Church (Moscow Patriarchate), but there is also a separate Orthodox Church, plus the Greek Catholic faith – namely, those who follow Orthodox rites but acknowledge the supremacy of the Vatican.

Putin’s key trope is that Ukrainians and Russians are ‘one people’, and he calls them both ‘Russian’. He starts with a myth of common origin: ‘Russians, Ukrainians and Belarusians are all descendants of Ancient Rus', which was the largest state in Europe’ from the 9th–13th centuries AD. Here, Putin uses the right word – Rus’ – not the modern word for ‘Russia’, which is Rossiya, a Hellenism only introduced in the 17th century. Ukrainians, Russians and Belarusians have all used Rus’ as part of their compound name at various times; but this only means they are kin, not the ‘same people’. Putin’s argument that the Ancient Rus’ were ancient Russians is, therefore, only one possibility out of four. The capital of Ancient Rus’ was Kyiv, making it proto-Ukrainian. Many Ukrainians say Russian history is really Muscovite history, beginning in the 14th century. Rus’ could be seen as a common enterprise of Ukrainians and Russians, or as an entity that existed before modern national identities were formed. Putin’s claim that ‘both the nobility and the common people perceived Rus as a common territory, as their homeland’ is highly dubious. The state was huge; communities of the ‘common people’ were pre-modern, parochial and illiterate.

Nowhere in his writings does Putin allow for Ukrainian subjectivity – for the possibility that Ukrainians might have their own opinion about who they are

In his latest ‘history’ broadsides, Putin also talks about the ‘decline of central rule and fragmentation’. Putin does not mention the dates for this process of fragmentation of the Ancient Rus’ entity, but it occurred between 1240 and 1654. He says that ‘people both in the western and eastern Russian lands spoke the same language. Their faith was Orthodox’. So, allegedly, nothing changed in four hundred years. But in fact, the ‘western’ lands –the area of today’s Ukraine – changed enormously. The Ukrainian language absorbed influences from all its neighbours: Polish, Turkic and other European languages. The Ukrainian Church that existed until 1686 and that was restored in 2019 was strongly influenced by the Renaissance, Reformation and Counter-Reformation – unlike the proudly isolated Russian Church.

Putin argues that, once most Ukrainians were under Russian rule – a process that took a long time, from 1654 to 1795 – ‘there is objective evidence that the Russian Empire was witnessing an active process of development of the Malorussian [Ukrainian] cultural identity within the greater Russian nation’. This is actually true, at least initially: in the 18th and early 19th century, Ukrainians and Russians both contributed to a common culture, like the English and Scottish did to British culture. But this stopped under the growing influence of Russian nationalism in the later 19th century; the empire limited the process of assimilation by adopting a Putinist policy, arguing that the Ukrainians were already Russians.

Putin also claims that ‘in the second half of the 18th century, following the wars with the Ottoman Empire, Russia incorporated Crimea and the lands of the Black Sea region, which became known as Novorossiya [New Russia]. They were populated by people from all of the Russian provinces’. This ignores the fact that the territory was populated beforehand for hundreds of years by Cossacks and Crimean Tatars. People did come from all over the empire to settle in the cities, as did so-called Black Sea Germans (Schwarzmeerdeutsche). But simple geography meant that most rural inhabitants came from the Ukrainian heartlands.

Political Misuses

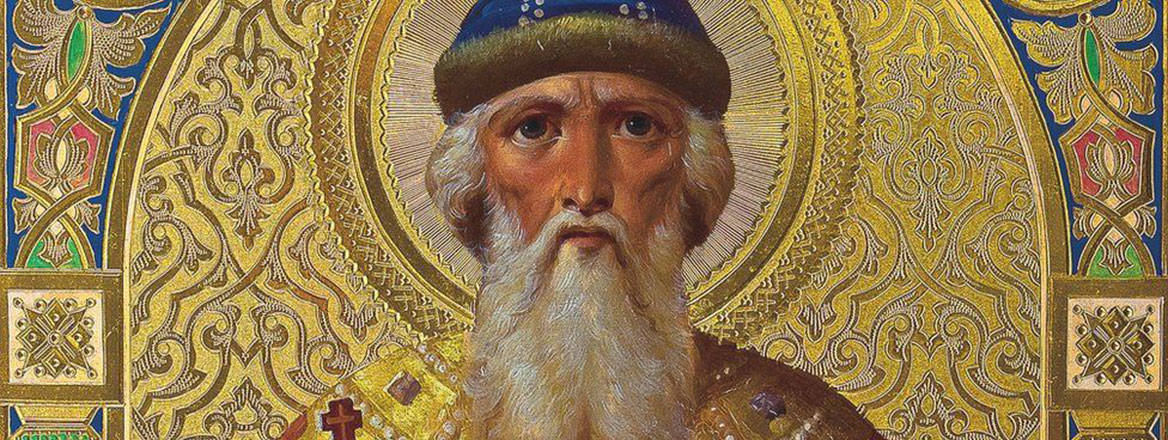

Putin’s claims about Crimea are simply colonial. He has asserted that the baptism of the medieval Prince Vladimir in Crimea in 988 gives Crimea ’sacral importance for Russia, like the Temple Mount in Jerusalem for the followers of Islam and Judaism’. But Vladimir – Ukrainian spelling Volodymyr – was Prince of Kyiv. His place of baptism is disputed by historians. He may have briefly conquered the Greek colonies in Crimea; but that matters little compared to the many centuries of the Crimean Tatar Khanate, from the 15th century until the Russian conquest in 1783, when the population was over 80% Crimean Tatar. The rest – Christian minorities – were Greek or Armenian, not Russian.

Russian rule in Crimea is a textbook case of settler colonialism: the Russians were not there in significant numbers before 1783, and Russian history-writing has deliberately written the indigenous people out of the picture. The Crimean Tatars are a civic nation made up of all local groups: Genoese Italian, Goth and Greek, as well as Tatar and Mongol. Significantly, Ukrainian historiography has shifted since 2014 towards stressing the parallel fate of Ukrainian Cossacks and Crimean Tatars in controlling Crimea and the Black Sea coast. In July 2021, Kyiv passed a law on the indigenous status of the Crimean Tatars.

Putin blames all Ukrainian self-assertion in the modern era on foreign intrigue: first, the ‘desire of the leaders of the Polish national movement to exploit the “Ukrainian issue” to their own advantage’; and then how ‘the Austro-Hungarian authorities … latched onto this narrative’ to harm Russia.

Also guilty, according to Putin, are the Bolsheviks, who set up a Ukrainian republic in the Soviet Union. ‘Ukrainization was often imposed on those who did not see themselves as Ukrainians’, claims Putin. Federalism was ‘the most dangerous time bomb, which exploded the moment the safety mechanism provided by the leading role of the CPSU [Communist Party of the Soviet Union] was gone, the party itself collapsing from within’. Putin concludes: ‘Modern Ukraine is entirely the product of the Soviet era. We know and remember well that it was shaped – for a significant part – on the lands of historical Russia.’ However, this assertion does not make sense if Ukraine and Russia are the same.

From 1939 to 1954, the Bolsheviks added territory to Ukraine from inter-war Poland, Czechoslovakia and Romania, together with Crimea in 1954. Putin proposes the nonsensical idea that ‘when you leave [the dissolution of the USSR in 1991], take what you brought with you’ – referring to the territory that the Ukrainian SSR had when the USSR was created in 1922. But, apart from Crimea, all of Putin’s Novorossiya – eastern and Black Sea Ukraine – was then part of Ukraine.

Overall, Putin ends his ‘historical’ peroration by blaming all problems on ‘external governance’ and referring to Ukrainian leaders as puppets of the West, a favourite trope of RT – Moscow’s overseas propaganda network – as well as Russian social media trolls. This shows just how much propaganda infuses all of this ‘history’; nowhere in his writings on the subject does Putin allow for Ukrainian subjectivity – for the possibility that Ukrainians might have their own opinion about who they are.

But the reality remains that Ukrainians and Russians have lived apart more than they have lived together; and when they lived together, they did not always get on. And the Ukrainians have the last word. In an opinion poll taken in July–August, just after Putin’s article came out, 70% of Ukrainians disagreed with Putin, saying that the Ukrainians and Russians are not one people.

The views expressed in this Commentary are the author’s, and do not represent those of RUSI or any other institution.

Have an idea for a Commentary you’d like to write for us? Send a short pitch to commentaries@rusi.org and we’ll get back to you if it fits into our research interests. Full guidelines for contributors can be found here.

In the News

Defence Secretary Ben Wallace cites Professor Andrew Wilson's Commentary piece in his article on the situation in Ukraine, published on 17 January, 2022. Read the article