Putin Makes the Case for the G7’s Clean Green Plan – Part 1

In the first of two articles, the case is made for a plan that can both increase the pressure on the West’s rivals and help save the planet.

Imagine a policy that simultaneously turns the screws on Russia, sends a powerful message to China not to flex its muscles, and helps save the planet. It sounds like snake oil. But the West already has the bare bones of such a policy – one designed to help the Global South decarbonise its economies rapidly. Think of it as a green ‘Marshall Plan’ or a green alternative to China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

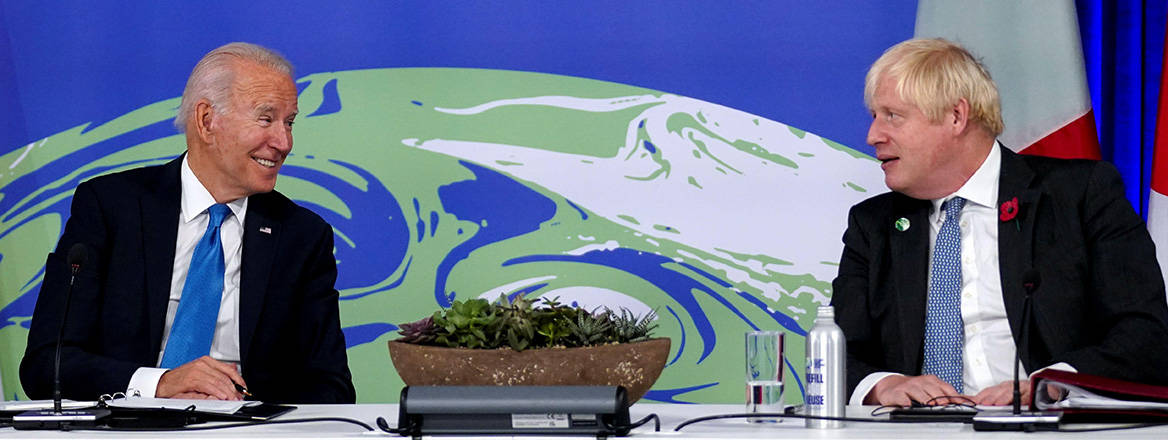

The Group of Seven (G7) large industrial countries launched this plan at their summit last June with an alphabet soup of acronyms – the US calls the plan Build Back Better World (B3W), the UK’s name is Clean Green Initiative (CGI), and the EU uses the term ‘Global Gateway’. They now need to put the plan on steroids to respond to Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine and help head off the threat from China.

Much is still up in the air regarding the West’s clean green plan – especially how it can mobilise trillions of dollars in private capital to fund it. But let us leave this to one side for the moment and consider the plan’s geostrategic and planetary rationale.

First, it can tighten the noose on Putin. It can do this by broadening the anti-Russia coalition to include more of the Global South. While rich liberal democracies have come together to strongly oppose Putin’s invasion of Ukraine, many poorer countries have been reluctant to condemn it – although the Bucha massacre may change that.

Some governments just do not see the advantage in criticising Russia. The war and the ensuing sanctions have already jacked up the prices of energy and grain, threatening massive hardship for any poor country that is a net importer of these basic commodities.

The embryonic green Marshall Plan, by contrast, speaks directly to two of the Global South’s main needs: to develop its economies; and to avoid the worst ravages of climate change.

Putin’s invasion of Ukraine makes this plan doubly relevant. Developing and emerging economies desperately need cheaper alternatives to hydrocarbons. But their already rickety finances have taken a further clobbering, so they do not have much money to invest in renewable energy. The West needs to bridge the gap.

What is more, it will be hard to cut off Putin’s source of income so long as he sells hydrocarbons to the Global South. India is already buying Russian oil at a discount. While the West could try to bully poor countries into not dealing with Russia, it would be more effective to help them meet their energy needs in an alternative, cleaner way.

Finally, some emerging economies may be able to produce renewable energy not just for themselves, but also for the West. North African countries are particularly well placed to send clean energy across the Mediterranean, helping the EU wean itself off Putin’s gas.

The West is paying the price for not reacting strongly enough when Putin invaded Georgia and then grabbed Crimea. It should not make the same mistake with China

It will certainly take time to ramp up renewable energy production in the Global South. But the Ukraine crisis could also drag on for years.

Message to China

The West’s clean green plan can also serve as a message to China about how it will suffer if it bails Russia out or throws its weight around in Taiwan or elsewhere.

Xi Jinping and Putin declared just before the Ukraine invasion that the friendship between their countries knew ‘no limits’. Washington is concerned Beijing will now help Moscow evade sanctions or supply it with military kit – and has warned China of the consequences of doing so.

But the effectiveness of any economic threats to Beijing – both now and in the future – will depend on how large a coalition the US can muster. Xi will calculate that the rest of the West will be reluctant to hit China with sanctions, given how dependent their economies are on trade with the country. His economy is 10 times the size of Putin’s and growing.

Xi will also be comforted by the fact that China has developed deep economic and diplomatic ties with large chunks of the developing world through the BRI. This massive infrastructure project, launched in 2013, aims to secure Beijing’s trade routes by land and sea.

The G7’s green Marshall Plan has from the start been seen as a response to the BRI. It aims to stop large parts of Asia, Africa and Latin America from falling into China’s orbit. If the West can build up alternative suppliers in the Global South, it will cut its dependence on Chinese imports. Xi will then be unable to blackmail the West in the way that Putin blackmailed the EU via its dependence on his gas.

Although China has a head-start, the West can still catch up, because the BRI has been losing momentum. Chinese investments in BRI partner countries, which peaked at $125 billion in 2015, fell to $47 billion in 2020. Recipient countries are finding it hard to service their debts to Beijing. Meanwhile, 35% of BRI projects are struggling with corruption, labour violations, environmental pollution and public protests, according to a recent survey.

The G7 set out various principles to guide its clean green plan. Many stand in stark contrast to the BRI: for example, a values-driven vision including transparency and sustainability; and a market-led approach, compared to China’s reliance on loans from state-owned banks.

The Ukraine crisis underlines the plan’s importance. The West is paying the price for not reacting strongly enough when Putin invaded Georgia and then grabbed Crimea. It should not make the same mistake with China – especially since Beijing may be a bigger long-term threat.

An ambitious clean green plan is one of the building-blocks the West will need to pressure Beijing to decarbonise its own export industries

It will take many years to foster green industrial revolutions in the Global South. But if the West drives its plan forward with ambition, Beijing will get the message now.

Clean Green Planet

Finally, the West’s clean green plan can create a clean green planet. The core idea is to help the Global South make fast and fair transitions to net zero via partnerships with individual countries, often known as ‘country-led platforms’. Carbon-intensive industries would be run down and clean ones created, while workers in old industries would be retrained so they could benefit from the transition.

South Africa, a coal-dominated economy, signed the first deal along these lines last year. The UK, France, Germany, the US and the EU agreed to provide it with an initial $8.5 billion in concessional finance, with the idea that much more private capital will then flow in. South Africa also announced a target of achieving net zero by 2050, making it one of the few large emerging economies with such an early target. By contrast, China has a 2060 target and India has opted for 2070.

Of course, the clean green plan cannot on its own stop the planet from frying. Rich countries, especially the US, will also need to do much more to cut their emissions. But a rapid transformation of the Global South will make a big contribution to the overall goal, as Africa, India and other parts of the developing world will not have to follow the West and China down the dirty path to growth.

What is more, a really ambitious clean green plan may be able to set off a virtuous circle that will prod China to do more for the planet. After all, Beijing may respond by further ‘greening’ the BRI – an initiative that has involved lots of coal, steel and concrete. This would be great for the planet because the West and China would then be competing to green the Global South.

An ambitious clean green plan is also one of the building-blocks the West will need to pressure Beijing to decarbonise its own export industries. After all, the West cannot credibly threaten to switch away from carbon-intensive Chinese exports unless it helps build up alternative green suppliers in other emerging economies.

The EU already plans to apply ‘carbon tariffs’ on some carbon-intensive imports from China and elsewhere. The German government wishes to use its presidency of the G7 to bring other countries with ambitious net zero plans into a ‘carbon club’, which would then collectively impose tariffs on non-members.

The snag is that it is easy to portray tariffs as a protectionist measure that will keep countries poor, so the EU’s plans could backfire in the Global South. India, Brazil and South Africa have already put out a joint statement with China expressing their ‘grave concern’ over carbon tariffs.

But things would look entirely different if the West were to help developing and emerging economies build up green industries. Countries that signed partnership deals could then be exempt from carbon tariffs. They might even start clamouring for tariffs to be imposed on countries such as China that continued to use dirty technology.

So, yes, there is a plan that can turn the screws on Putin, deter Chinese bullying and save the planet. But can the West deliver it at scale? That is the topic of the next article.

Read Part 2 here:

The views expressed in this Commentary are the author’s, and do not represent those of RUSI or any other institution.

Have an idea for a Commentary you’d like to write for us? Send a short pitch to commentaries@rusi.org and we’ll get back to you if it fits into our research interests. Full guidelines for contributors can be found here.

WRITTEN BY

Hugo Dixon

- Jim McLeanMedia Relations Manager+44 (0)7917 373 069JimMc@rusi.org