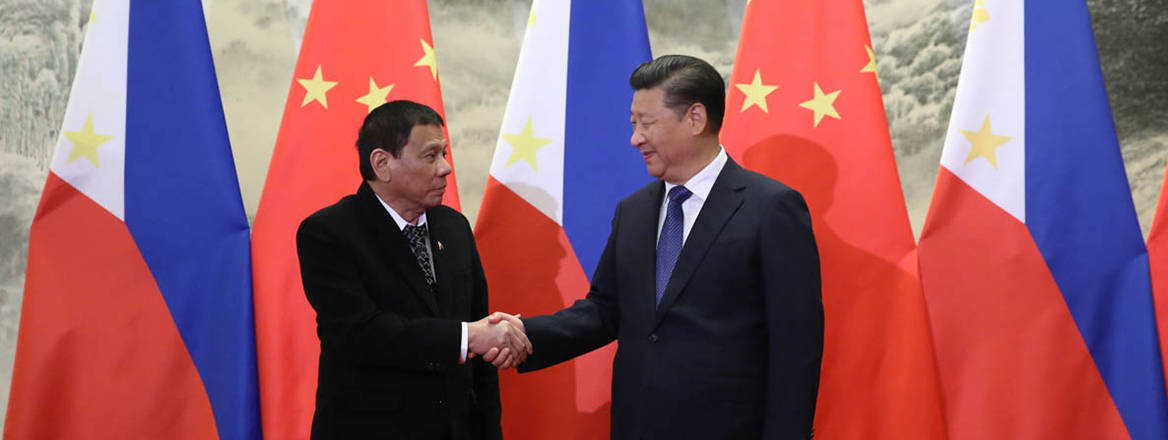

The Duterte administration’s mixed foreign policy approach towards China has yielded some positive outcomes for the Philippines, while also serving the purpose of strategic ambiguity.

Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte’s China policy has long been condemned as appeasement, amid claims that jumping on the bandwagon of Chinese growth has led to a failure to rein in Chinese activities in the South China Sea (SCS). Two issues stand out: President Duterte’s sclerotic attitude towards China, and his supposed disregard for the 2016 SCS Arbitral Award won by the previous Aquino administration. Duterte has stated that China is ‘in possession’ of the SCS, that the Philippines is ‘indebted’ to China, and that going to war with China would be ‘suicidal’, running the risk of setting off a ‘nuclear war’ if the alliance with the US is leveraged in the SCS. He even framed the tensions in the SCS as a byproduct of China–US great power rivalry, claiming that the Philippines could become either a ‘province of China’ or a ‘colony of the US’.

For these reasons, Duterte has been lambasted by domestic critics for presenting the public with a false choice in which the only options vis-à-vis China are war or cooperation, with some claiming that his foreign policy is ‘pro-China’ and ‘anti-US’. Regarding the Arbitral Award, Duterte has been denounced for echoing China’s official position that the Award cannot be enforced as it is a ‘mere piece of paper’, defying his earlier speech at the UN General Assembly – which drew praise even from oppositionists – where he said that ‘The Award is now part of international law, beyond compromise and beyond the reach of passing governments to dilute, diminish or abandon. We firmly reject attempts to undermine it’.

The above statements are, however, mostly observations at the level of the individual. They are undoubtedly important, as in the hierarchy of policy statements those of the president matter most – especially given that in the Philippines, the president is the ‘chief architect’ of foreign policy – but a number of other factors are also at play.

Analysis at the Macro Level

The Duterte administration has been accused of lacking a coherent strategy, because while Duterte himself has struck a conciliatory tone towards China, government ministries such as the Department of Foreign Affairs (DFA) and Department of National Defense (DND) continue to file diplomatic protests against China, asserting the Arbitral Award at the UN and occasionally making statements in support of the US. For example, DND Secretary Delfin Lorenzana has mentioned that he welcomes the Biden’s administration’s renewed commitment to Asia as it will help to ‘counterbalance’ China, while DFA Secretary Teodoro Locsin Jr welcomed the establishment of the Australia, UK and US (AUKUS) trilateral security partnership for maintaining a favourable regional balance of power. Accused of being a dictator at home who dominates all decision-making institutions, Duterte has ironically chosen to keep the heads of the DFA and DND – unlike other appointees who he has fired – despite their policy positions appearing to openly conflict with his.

What this implies is that President Duterte’s policy pronouncements are not in and of themselves instructive regarding the overall foreign policy behaviour of the Philippines, and that there is more to the country’s approach towards China than meets the eye. Thus, there is a need to look beyond statements and weigh them against various material indicators. If only statements were to be considered, then instances such as Hitler’s non-aggression pact with Stalin or Imperial Japan’s public denial of plotting to bomb Pearl Harbor would always be taken at face value. Moreover, only considering policy statements would sideline the other modalities of policy analysis. This is where the role of ministries – as decision-making units – and domestic politics comes into play. These two factors arguably account for why Duterte can be influenced by the opinions of his cabinet members, and it is because of public pressure that Duterte finds the need to make popular but baffling policy decisions so as to deflect criticisms against him, divert political attention and/or bargain with the US.

Specific policy actions that may be attributed to the role of Philippine government ministries include the ongoing modernisation of the Armed Forces of the Philippines, with plans to import Brahmos missiles from India and additional frigates from South Korea; the first ever docking of a naval vessel on the Philippine-occupied Pag-Asa Island in the Spratlys; increased sovereignty patrols in the SCS; the expulsion of Chinese fishing and naval vessels; and the renaming of ‘Benham Rise’ – where China has conducted maritime activities in recent years – to ‘Philippine Rise’. And when there were reports in 2019 that China would develop the strategically located Fuga Island, Duterte ordered that 20 hectares of the area be allotted for a naval base.

The Philippines’ conspicuously constructive approach towards China has served as a cover for the country’s continued strategic alignment with the US

US military assistance to the Philippines has also continued, and the most important Philippines–US military exercise, the ‘Balikatan’ (Shoulder-to-Shoulder), has resumed. One could even argue that the Philippines–US alliance has emerged stronger under Duterte, as Washington’s assurances that it would come to the aid of Manila in the event of an armed assault in the SCS have become clearer – whereas during the Obama administration, the most common statements were that the US ‘does not take sides’ on competing maritime and territorial claims in the SCS. Additionally, the US has issued a strong statement regarding the Scarborough Shoal, should China seek to occupy or reclaim it. Meanwhile, although he is known for being anti-American, Duterte surprisingly granted an absolute pardon to a US soldier who was found guilty of killing a Filipino transgender person.

More recently, the Philippines–US Visiting Forces Agreement – which had been impulsively suspended not in an attempt to appease China, but because of US criticisms of the Duterte administration on human rights issues – was reinstated. And when previously asked whether the alliance with the US should be abrogated, Duterte said that it is not for him alone to decide. At the same time, joint hydrocarbon development with China in the SCS is still in the works, with the Philippine side placing emphasis on creating a legal framework that would not go against the Philippine Constitution or the Arbitral Award. In relation to this, Duterte has stated that he will dispatch the Philippine Navy if China unilaterally drills for oil in the SCS. In direct contrast to his defeatist statements regarding China, Duterte has also dared the US, France and the UK to help the Philippines reclaim its territories in the SCS.

It is important to view President Duterte’s foreign policy beyond the context of US–China rivalry. For instance, the Philippines has implemented a policy of stronger engagement with the Quad grouping of countries, including Japan, Australia and India, and has carried out military and coastguard exercises with all three states. Furthermore, it should be noted that the Duterte administration rejected China’s bid to develop Subic Port, a port strategically located on the Philippines’ Luzon Island, and has instead considered an Australian firm as a partner for this project. And despite media claims that China is dominating projects in the Philippines, Japan remains the country’s largest source of official development assistance and the leading financier of the Philippine government’s ‘Build, Build, Build’ infrastructure programme. Based on these facts, it can be stated that the Duterte administration has practiced ‘selective engagement’ vis-à-vis China.

Complex Hedging?

The mixed signals from the Philippine government – that is, active engagement with China and the simultaneous enhancement of relations with other countries – are a manifestation of a multipronged foreign policy. This could imply two things: a naturally inconsistent approach, or a deliberate ploy to sow confusion. Because of the confusing messages from the Duterte administration, leftist activists have called Duterte a puppet of both China and the US. Regardless of whether it is strategic or tactical, proactive or reactionary, the administration’s current foreign policy – while in need of improvement – has yielded some positive outcomes for the Philippines, and has incidentally served the purpose of strategic ambiguity.

Moreover, the Philippines’ conspicuously constructive approach towards China has served as a cover for the country’s continued strategic alignment with the US. If President Duterte’s foreign policy contains elements of appeasement and balancing, this might be construed as a form of hedging, albeit one that is complex and not conventional. This is because unlike traditional hedging, where policy actions towards one state are counterbalanced by policy measures towards another, policy rhetoric is being offset by policy engagement vis-à-vis other states.

The views expressed in this Commentary are the author’s, and do not represent those of RUSI or any other institution.

Have an idea for a Commentary you’d like to write for us? Send a short pitch to commentaries@rusi.org and we’ll get back to you if it fits into our research interests. Full guidelines for contributors can be found here.