The Pentagon Leak: Childish Stunt or Dangerous Trend?

The arrest of a US serviceman for allegedly leaking Pentagon secrets on an online gaming forum has garnered widespread attention. How concerned should security services be about this case?

On 13 April, 21-year-old Massachusetts Air National Guardsmen Jack Teixeira was taken into custody for allegedly leaking of hundreds of classified military documents related to the war in Ukraine to his online gaming community. The leak may well be ‘unusual even in the small world of leak cases’. However, his case is not unusual – we would argue – when it comes to gaming platforms, tight-knit online communities, and the increasing rates of misogyny, racism and violent extremism present in such communities, which is something that we have been working to better understand.

Over the last two years, we have been researching how video games and online gaming platforms intersect with radicalisation, extremism and other social harms. Through the establishment of the Extremism and Gaming Research Network, we have been working alongside a wide-ranging, global group of colleagues from research, practitioner, policy, security, industry and other backgrounds to understand the potential positives and negatives of socialisation within the online gaming environment, which has largely been ignored by governments, security and intelligence services, and tech platforms. Though the Teixeira case does not yet – as far as is known publicly – directly concern violent extremism, there are significant elements in his case that identify with a pattern.

Media coverage of the gaming communities frequented by Teixeira is generally dismissive of their importance. However, researchers have found that online gaming communities form exceptionally strong in-group connections that frequently extend to offline relationships and actions. Many media reports seem to equate the young age of Teixeira with a simplistic need to show off by leaking information to his online friends. However, a more nuanced analysis depicts the meaningful relationships developed between him and his peers online.

The social bonds built through shared gamer identities can be profoundly powerful and a source of strength. However, like all relationships, these connections can be manipulated and become harmful. Teixeira’s willingness to turn over classified documents to his closest gamer friends likely has less to do with his youth or a particular vulnerability, and more to do with the gamer community with whom he shared a deep affinity and that he had a desire to protect. In the words of another group member, Teixeira demonstrated a ‘little bit of showing off to friends, but as well as wanting to keep us informed’. It is essential to emphasise the centrality of socialisation to this case. The connection to online gaming is important, not only because of the games he played and the platforms he used, but also because of how this community-driven online gaming experience creates bonds and strong peer-group dynamics.

Psychologists have observed that online relationships, especially those built through shared gaming experiences and ‘raids’ (a term used for missions in some online games), can mirror the intensity of offline bonds developed in military units or those engaging in other high-intensity activities. Identity fusion occurs when a group identity overwhelms the complex layers of social identity for an individual. While it may seem difficult to believe that online gaming can create bonds of the same strength as ‘real-world’ intensive unit-building experiences, the reality is that when an individual’s identity becomes strongly fused with their online (gamer) activities, it actually elicits the same physiological responses. Among gamers in the US polled last year, exceptionally strong levels of gamer identity fusion were correlated with a willingness to fight and die (for other gamers), higher rates of sexism and racism, and the endorsement of beliefs and policies centred on ideas of white nationalism.

Games – and the many subcommunities of gamers – extend beyond simple gameplay to many adjacent platforms, sites and online spaces which share cultural norms and lexicons

What we know about the offline context of unit building within the security forces is that often in the more intensively trained incident-response or combat-focused units, hypermasculine, misogynist and racist behaviour is allowed and even encouraged as an element of in-group/out-group formation of unit identity. While Teixeira was not in a special forces unit, there is still a degree of this cultural influence across the military that needs to be addressed. Otherwise, as may have been true in this case, the cultural familiarity with misogyny, racism and other elements of othering can create an increasing link to far-right violent extremist ideologies, as well as between real-world and online identities where these belief systems are commonalities.

The Online Gaming Environment

Open source examination of profiles linked to Teixeira reveals his taste in games and user groups. There are a few ways in which to break down the uses of online games and their potential nexus with extremism. This is important in the case of Teixeira because the games and online communities he frequented overlap significantly with those we know to be popular among far-right actors and that contain a significant amount of sexist, racist and other extreme content and communication.

The game Arma 3 stands out for its popularity as a military simulator (Milsim) game. Its accurate weaponry depictions have been used as a tool by both far-right violent extremists – including reportedly the Buffalo shooting perpetrator last year – and Islamic State sympathisers via an array of downloadable mods (modified games and maps). Additionally, among the many regular users of both Minecraft and Garry’s Mod are far-right and racist actors, who continue to exploit the ability of users to build anything of their choosing in these types of games.

Games – and the many subcommunities of gamers – extend beyond simple gameplay to many adjacent platforms, sites and online spaces which share cultural norms and lexicons. Open source research shows that Teixeira’s community communications took place largely on Steam. Steam is the most popular game distribution and in-game communication platform, with over 120 million monthly users. Some of the Steam groups he appears to have joined include one named after a component of the Canadian Light Infantry, the ‘3rd Light Infantry Company 3rd LIC’, along with several named after or associated with private military contractors, such as ‘South Bridge Contractors - Arma SBCPMC’ and ‘ESF PvP [PMC] group ESFPMC’.

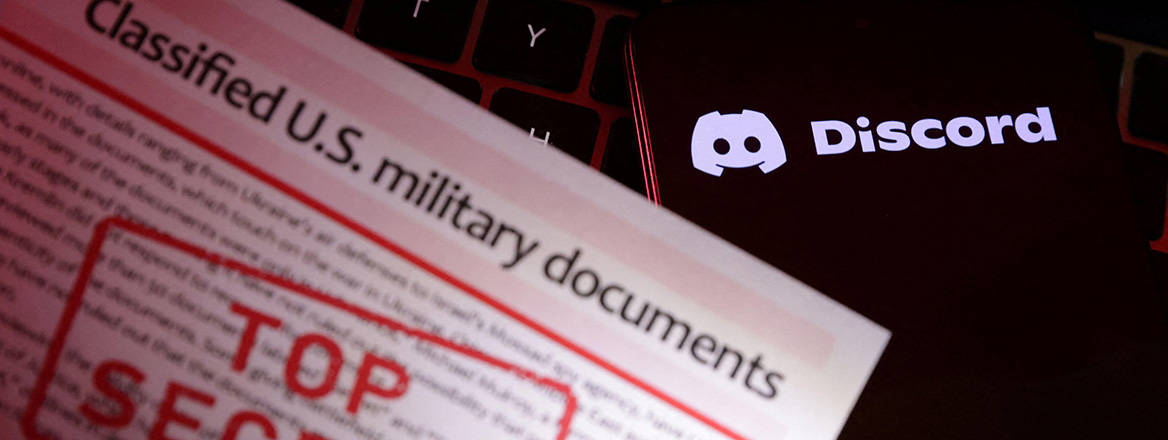

Meanwhile, his use of Discord – where Teixeira appears to have initially shared the leaked documents – has received far more media attention. This platform is immensely popular with gamers and started as a service dedicated to hosting text and audio messaging alongside games. Today, Discord boasts nearly 140 million monthly active users across the world on individual servers (communities) dedicated to nearly every topic imaginable – from gaming to homework, music, niche technical fields and beyond.

Improving the resilience of platforms, gamers and affinity communities like educators and parents to disinformation efforts should be a priority

Given the ability of users to form closed servers of their own, Discord has been popular with various far-right actors, including the organisers of the deadly 2017 Unite The Right rally in Charlottesville, as well as the Buffalo shooter, who used it to draft his manifesto. However, Discord is not a fully anonymous or even encrypted platform, and its improved trust and safety efforts work closely with law enforcement agencies, which has led far-right actors on terrorist- and violent extremist-operated websites to caution against using the platform. Still, illegal and so-called ‘lawful but awful’ content remains on Discord. Even the name of the server where Teixeira appears to have initially posted the classified material, ‘Thug Shaker Central’, is a racist and nominally homophobic reference to a pornographic series popularised as a derisive joke among online trolls.

The investigative OSINT outfit Bellingcat has also modelled the flow of the leaked documents from the original Thug Shaker Central Discord server to adjacent Minecraft-related servers and afterwards to Telegram and 4chan. Again, the overlap between these platforms reflects potential avenues that extremist actors can exploit in gaming spaces: after moving from in-game chats where like-minded individuals can meet, extremists may invite sympathetic individuals to join them on shared servers on Discord or Telegram. They may then further signpost to more intense content on terrorist- and extremist-operated websites or on adjacent ‘terrorgram’ Telegram channels, while relying on encrypted chat services like Signal or Element messenger for operational communications.

As other commentators have observed, the leaking of classified documents by military personnel through gaming services is not a new trend. At least three and as many as 17 separate incidents have been associated with the Milsim War Thunder, where players have posted classified blueprints on game forums for US F-16 fighter jets, UK Challenger 2 tanks, French Leclerc S2s and Chinese DTC10-125 tanks. In an effort to debate the realism of in-game depictions, players with access to classified information have knowingly posted materials to prove their points of view in online debates. The irony of online debates resulting in real-world national security risks seems to have been lost on the individuals involved.

Simultaneously, intelligence services see a clear utility in exploiting such lapses caused by the allure of games, tight-knit gaming community relationships, and the psychological appeal of gaining ‘cred’ online through knowing something the general public does not. Citing a retired US military official, the Financial Times reported that ‘Russian, Iranian and Israeli operatives are believed to have tried to use gaming chat rooms, on Discord and elsewhere, to befriend – and eventually recruit – disaffected young soldiers, especially those expressing right-wing or anti-establishment views in what they considered private chat’.

While Teixeira may not have been groomed or motivated by foreign intelligence actors, the potential for future exploitation is clear. Security clearance vetting processes, document classification handling procedures, and counter-intelligence operating procedures need to adapt accordingly. Beyond intelligence-gathering operations, the utilisation of gaming and gaming-adjacent platforms to engage in malign influence operations is also of concern. Improving the resilience of platforms, gamers and affinity communities like educators and parents to disinformation efforts should be a priority, as well as addressing hypermasculine, sexist and racist cultures within security services to reduce the vulnerability of trained and cleared service members to the enticements of negative socialisation, radicalisation and recruitment in online gaming spaces.

The views expressed in this Commentary are the authors’, and do not represent those of RUSI or any other institution.

Have an idea for a Commentary you’d like to write for us? Send a short pitch to commentaries@rusi.org and we’ll get back to you if it fits into our research interests. Full guidelines for contributors can be found here.

WRITTEN BY

Galen Lamphere-Englund

RUSI Associate Fellow, Terrorism and Conflict

Dr Jessica White

Acting Director of Terrorism and Conflict Studies

Terrorism and Conflict

- Jim McLeanMedia Relations Manager+44 (0)7917 373 069JimMc@rusi.org