Peering into China’s Decision-Making: What are the ‘Xinjiang Papers’?

A stash of Chinese government documents is providing a unique insight into the country’s repression of its Muslim minority, and President Xi Jinping’s direct responsibilities.

The dangers of conducting research on the ground in China’s Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region mean that significant information on security policy comes from Chinese government document leaks, including the ‘Karakax List’ and ‘China Cables’. These provided invaluable evidence on policy implementation, but less on the party-state’s decision-making processes. The ‘Xinjiang Papers’ leak, acquired by London-based Uyghur Tribunal and analysed by Dr Adrian Zenz, now reveals the centralised chain of command behind those policies.

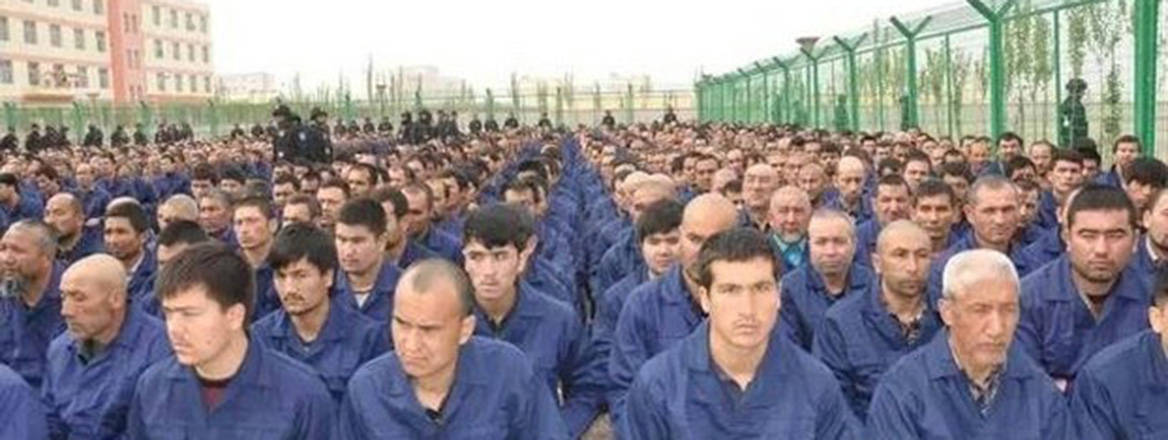

Under Xi Jinping’s rule of the People’s Republic of China (PRC), up to three million Turkic-speaking Muslims have been extralegally detained and subjected to invasive surveillance, sexual violence, child-separation and psychological trauma. Nearly 10 million Uyghurs and Kazakhs outside the camps mediate networks of forced labour, hi-tech surveillance systems, and checkpoints and interpersonal monitoring. The ‘Xinjiang Papers’ include speeches from Xi and his appointed regional party chief, Chen Quanguo, alongside Central Party Committee commands to all tiers of government down to the county level, linking observed policies to central commands.

The documents provide detailed evidence of the centralised construction, implementation and monitoring of policy in Xinjiang. Xi’s centralisation of authority – ending presidential term limits, rapidly acceding to the Central Military Commission, and inscribing ‘Xi Jinping Thought’ into the Party’s constitution – includes micromanagement of security in Xinjiang. The ‘Xinjiang Papers’ show that violent targeting of Uyghurs intensified in response to central party directives to local leaders.

How Do We Know the ‘Xinjiang Papers’ are Authentic?

I reviewed transcriptions and analysis of the 'Xinjiang Papers' by Dr Adrian Zenz. My full statement is publicly available alongside Professor James Millward's and the Tribunal hearing discussing their significance. Original documents cannot be released in order to protect the source’s safety. I would have refused to review the analysis without them. Dr Zenz’s detailed authentication methods include comparison with the related New York Times ‘absolutely no mercy’ leak, crosschecking against publicly available documents, locating sources quoting the documents, tracking use of repeated terms across documents, and verifying official formatting.

Quotes and direct references to the documents are online but not full texts – familiar experiences from failing to find documents from the widely quoted Xinjiang Working Group Meetings convened to assess policy responses after the 2009 Ürümchi violence. The leak’s source cannot be identified because these materials are disseminated and studied so widely. The content repeats concepts and policies (e.g., Sinicisation, Three Evils, Great Revival) that are familiar to those working with official documents. These are circulated widely through official media, party announcements, local news on cadre meetings, ‘patriotic education’ texts, and political slogans. The papers follow established patterns in official documentation in titling and structure, narrative explanations, and content referring to policies widely observed across China.

Who Commands Security Policies in Xinjiang?

The documents’ chronology is highly significant. In 2014, Xi gave fiery speeches and orders to implement new policies to resolve Xinjiang’s problems in a ‘painful period of interventionary treatment’. Chen Quanguo subsequently issued orders to ‘round up all those who should be rounded up’. By 2017, the tone shifted, with the Central Party Committee reining in local leaders for loose management, and Wang Yongzhi and Gu Wensheng being expelled from the party for ‘violations of discipline’ (documents 9 and 11).

The ‘Xinjiang Papers’ show that violent targeting of Uyghurs intensified in response to central party directives to local leaders

Document 10 (‘Strengthening and progressing Islam Work under new conditions’), a ‘suggestion’ (yijian), is a guide to action serving as a broad set of rules for cadre behaviour from the Central Party Committee. ‘Suggestions’ create momentum in the party-state bureaucracy, pressuring cadres to explain behaviour and policy implementation through its ideological and institutional framework. Document 10 is widely studied by officials, with ‘all cadres’ expected to ‘follow its spirit’ and ‘all regions and related departments’ expected to implement its ‘concrete measures’.

Sub-section 2 describes ‘problems in basic Islam Work of not being able, willing, or daring to monitor’; therefore, ‘the party’s leadership of Islam Work is being urgently strengthened’. This demonstrates how policy in Xinjiang is designed and disseminated, and implementation monitored and policed by the top levels of the party-state. This matches existing knowledge of the PRC’s centralised political system: the centre commands, provinces implement variably, and the centre reins them in according to the issue’s gravity.

Which Policy Areas are Included in the ‘Xinjiang Papers’?

The policy content corresponds with what Xinjiang-focused scholars and international media have observed: mosque demolitions, mass internment, coercive birth controls, forced labour, ‘population optimisation’ as a euphemism for dispersal, and ‘Sinicisation of religion’. However, the papers show that these specific practices are designed and monitored by the central party-state, reflecting Xi’s micromanagement approach to security.

Document 10 tells a story of rising ‘religious fever’, with waves of ‘de-Sinicisation’, ‘Saudi-isation’ and ‘Arab-isation’ that demand stricter policy and implementation. Islam in China is described as ‘harmonious’, but ‘global Islam’ is a problem of ‘infiltration’. Sinicisation, therefore, is needed for national and ‘ideological security’. These are widely observable narratives, yet the papers contain more specific policy details than publicly available documents. Sub-section 7 explains that the ‘principle is no new construction or establishment of religious venues’ and to ‘demolish many, build few, and merge mosque construction’.

What Does Security Mean in Xi’s Party-State?

The meaning of security to the party-state is expansive and nebulous, sharing familiar concerns with UK policymakers but also including culture, ideology and everyday identity. Party-state education texts after the 2009 Ürümchi violence described ‘making friends, recognising each other’s hometowns, and student parties’ as security problems, with identity being securitised such that only the ‘Three Evils’ (separatists, terrorists and extremists) could consider Uyghurs a Turkic or Islamic people. The internal logic that Uyghur identities are a national security threat has been self-defeating, fomenting increased opposition and resistance among Uyghurs.

Xi has intensified the party-state’s focus on ‘political security’ as well as ‘ideological’ and ‘cultural security’, with ethnic assimilation (‘fusion’) policies considered to provide a settlement of national ‘contradictions’. Document 3 (‘Responding to the stimulus of a series of terrorist attacks in the UK’) orders construction of ‘convenience police stations’ to monitor everyday behaviour and instructs cadres to arbitrarily ‘round up all who should be rounded up’ for ‘transformation education’ in internment, contrasted against the UK government’s supposed failing ‘human rights over security’ counterterrorism approach.

Within the totalitarian logic of ‘ideological security’, Uyghur identification with language, history and religion is seen as a national security threat

‘Political security’ in the ‘Xinjiang Papers’ is an authoritarian approach, referring to the maintenance of centralised party institutions. ‘Ideological security’ denotes citizens’ self-identification with the content of the party-state’s ‘historical resolution’, in which China’s identity was formed during the Qin-Han dynasties (221 BCE–220 CE), absorbing peripheral cultures, and its history has entered a ‘new era’ under Xi’s rule. Within the totalitarian logic of ‘ideological security’, Uyghur identification with language, history and religion is a national security threat, reflected in internment practices and the ‘75 signs’ of religious extremism.

Will Xi Change Policy Direction?

Xi’s description of Xinjiang policy as ‘completely correct’ suggests the central party-state will continue its current policy direction. Xi has staked his legitimacy on its success and will not choose to publicly change course. However, the ‘Xinjiang Papers’, and previous leaks, do reveal internal concerns regarding local leaders’ willingness to implement Xi’s policies. The transfer of interned Uyghurs to forced labour facilities and standard prisons across China also suggests that Xi’s ‘painful period of 'interventionary treatment’ means eventual scaling-down of the camps and attempts to create a totalitarian hi-tech surveillance state with most Uyghurs in forced labour or prison.

The capacity for intergenerational transmission of Uyghur identity or organised resistance in such a society is slim. Intergenerational separation and family breakups are key tactics in Xi’s genocidal practices. Meanwhile, Uyghur diasporas in London, Paris, the US, Australia and Canada create social spaces to maintain their identity and conduct related research. The success of Uyghurs’ efforts depends on the willingness of democratic societies to guarantee freedom from harassment by the Chinese authorities and to support their research with rights to academic freedom.

The views expressed in this Commentary are the author’s, and do not represent those of RUSI or any other institution.

Have an idea for a Commentary you’d like to write for us? Send a short pitch to commentaries@rusi.org and we’ll get back to you if it fits into our research interests. Full guidelines for contributors can be found here.