Germany’s China Policy of ‘Change Through Trade’ Has Failed

Europe’s biggest trading country needs to lend its weight to Europe’s efforts to rethink relations with China.

We need to talk about Germany. Let us start with an inconvenient truth: German governments, both past and present, have consistently prioritised trade with China over other enlightened German national interests, for example, democracy and human rights. Such commercially-driven engagement with China, however, is neither a value-free proposition nor quite as substantial as corporate propaganda suggests.

Economic Links

Statistics can help shed light on Germany’s commercial relationship with China. From a macroeconomic perspective, the Chinese export market is relatively insignificant. In 2018, Europe accounted for 68.5% of German exports, whereas only 7.1% of German exports went to China. But such hard facts have not stopped pundits exaggerating the importance of the Chinese market for Germany’s export-oriented economy.

The picture is admittedly rather different on a company level. Here, some German CEOs have created over-dependencies on the Chinese market instead of diversifying their global portfolio. Volkswagen is a case in point. Under CEO Herbert Diess’s leadership, VW has just finalised its biggest M&A in China and invested €2.1 billion in two Chinese electric vehicle companies. Diess gained notoriety when a BBC journalist asked him about the wisdom of opening a factory in Xinjiang, where Uyghurs and Kazakhs are held in internment and labour camps against their will. Diess feigned ignorance to protect VW’s considerable investments in China. Other German companies such as Siemens and BASF are manufacturing in Xinjiang, too. And in 2019 BASF started investing more than €10 billion by building an integrated petrochemicals complex in southern China.

Such company-level dependence on the Chinese market is problematic since corporate lobbying will try to prevent failure in order to recover sunk costs in China, as may be the case should the German government decide to decouple its manufacturing links from the Chinese economy as part of the lessons to be drawn from the coronavirus pandemic.

A Change?

But how likely is a major change in Germany’s China policy? A key problem of Germany’s approach towards China lies in the way foreign policy is conducted in Berlin. Human rights expert Rosemary Foot once pointed out that: ‘Compared with the USA, other governments have operated in more permissive environments when it has come to setting the priorities for their China policies. Foreign policy-making in European capitals, for example, unlike in Washington, tends to be a more élitist affair, and generally less confrontational. The US separation of powers, lack of party discipline, and sense of mission largely account for America’s more politicized approach’.

Since German foreign policy is a highly elitist affair, corporate lobbyists have ample opportunities to shape the government’s strategy towards China. One has to bear in mind that Germany’s political economy is highly corporatist. The revolving door between the world of German politics and car manufacturers is very well documented. This means that corporate interests will always loom large when Germany’s China policy is being discussed, almost always away from the public’s gaze. And it is not only export-oriented industries which are informing policy discussions. In 2019, for instance, Deutsche Telekom was already in advanced talks with the Chinese company Huawei to procure radio transmission gear for its 5G network before talks were put on hold due to uncertainty about the future regulatory environment and that too had an impact on the German government’s deliberations.

In light of such short-sighted business dealings it is all the more heartening that German politicians are finally waking up to the reality that we are facing a systemic problem which requires decisive countermeasures. Whether it is the incarceration of 1.5 million Uyghurs and Kazakhs in mainland Chinese internment and labour camps, the suppression of Hong Kong’s democracy movement, or the cover-up of Covid-19, none of these fundamental disagreements will go away by merely expanding trade and investment with China. The long-term mantra of German business executives and politicians that change in China would come through trade was always a deeply cynical approach, since there never was much of a chance of this being realised. In 2020, however, the ‘change through trade’ argument has truly run its course and should be replaced with a more realistic approach.

But what could this new approach to China look like?

Repositioning the EU’s Approach

For a long time European politicians and diplomats have argued that only ‘dialogue and cooperation’ will entice the Chinese Communist Party to become a more responsible global stakeholder. This position has been criticised by French political scientist François Godement as a form of ‘unconditional engagement’. In the past, elite channels were used to improve the EU–China relationship. They were not only highly exclusive but broader inter-cultural dialogue and cooperation between European and Chinese civil societies were simulated rather than practised. When conducting a series of in-depth interviews with European Commission and European External Action Service diplomats in Brussels and Beijing, the British academic Max Roger Taylor found a ‘worrying culture of complacency and self-censorship in EU diplomacy with China’. Now paradigmatic foreign policy change is coming, albeit very slowly and only due to increasing public pressure. On 25 May 2020, Europe’s top diplomat, Josep Borrell, addressed a gathering of German ambassadors. He told them that the EU and its member states need to develop a ‘more robust strategy’ toward China.

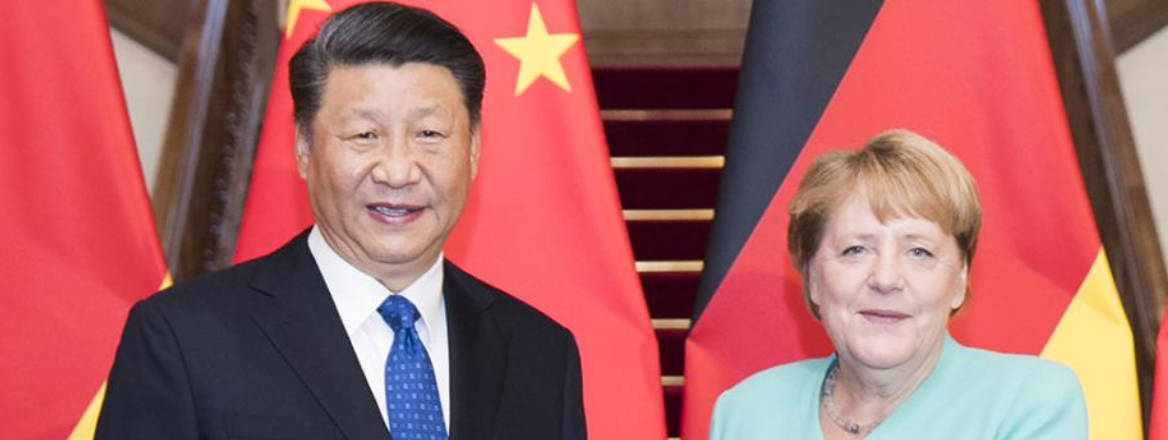

It is self-evident that the EU will struggle to develop a more assertive policy on China without the backing of Germany. But how can German diplomats change tack if Chancellor Angela Merkel is unwilling to give directions? It is understandable that a country which is guilty of the horrors of the Holocaust is wary of playing an assertive global leadership role. But there is also a real danger of a Machtvergessenheit, where Germany in fact underutilises existing leverage in global affairs. Germany is often praised for facing up to its Nazi past. ‘Never again’ has long been a guiding principle of an ethical German foreign policy. But how then can the German government remain silent when Uyghurs and Kazakhs are incarcerated, Hongkongers have their civil and political liberties stripped away and Taiwanese are threatened with military annexation?

China under General Secretary Xi Jinping is regressing on all fronts: human rights violations are now systemic and endemic, even the mildest forms of criticism by Chinese academics are no longer tolerated, and the Chinese Communist Party is increasingly aping Russian disinformation strategies in Europe. Germany must now ask if it will continue to actively support such a regime. So far Chancellor Merkel has failed to answer this question. She has been unable to articulate what enlightened German ideational and material national interests look like beyond trade and investment. Merkel’s unwillingness to set red lines not only undermines German foreign policy towards China but also makes it harder to develop a new and more assertive European strategy towards China.

At a time of heightened geopolitical tensions between the US and Communist Party-led China, Europe can no longer afford Germany’s unprincipled and failed China policy of ‘change through trade’. In 2020, it is abundantly clear that China did not liberalise and democratise as a result of German car manufacturers enriching themselves by selling cars to China. Since the political situation in mainland China and its periphery has deteriorated to such a great extent, business as usual is no longer an option. What is now required is a Europe-wide approach which repositions the EU in light of Xi’s increasing totalitarianism. While trade clearly matters, European values need to be defended, too. Chancellor Merkel should abandon her failed China policy and join Europe’s search for a more principled approach towards China.

Andreas Fulda is a Senior Fellow at the University of Nottingham Asia Research Institute and author of The Struggle for Democracy in Mainland China, Taiwan and Hong Kong: Sharp Power and Its Discontents.

The views expressed in this Commentary are the author's, and do not represent those of RUSI or any other institution.