The Current State of Ukrainian Mobilisation and Ways to Boost Recruitment

Faced with a drop-off in the number of people volunteering to join its armed forces, Ukraine is increasingly turning to technological solutions to bolster its recruitment drive.

Recently, both in the Western and Ukrainian media, there has been a discussion about the problems associated with the recruitment of new military personnel into the Armed Forces of Ukraine. This coverage presents the current situation in a distorted form, which often does not correspond to reality and completely misdirects uninitiated and even partially initiated observers.

First of all, this concerns the very facts of mobilisation in Ukraine. From the end of 2023 to the beginning of 2024, changes to the Law ‘On Mobilisation Preparation and Mobilisation’ were adopted in Ukraine, which were supposed to simplify its procedures, and were accompanied by sharp political debates regarding some of its controversial proposals. In connection with this, much speculation began to appear to the effect that Ukraine allegedly has not mobilised, and therefore is not able to provide the Armed Forces of Ukraine with the necessary manpower. Such assessments are incorrect and do not reflect the real problems that Ukraine is trying to solve.

According to the Constitution of Ukraine, the protection of its sovereignty and territorial integrity – although entrusted to the Armed Forces of Ukraine – is the duty of every citizen. From the first day of Russia’s full-scale invasion in February 2022, the Ukrainian government decided to impose martial law and declared general mobilisation, along with a ban on men aged 18 to 60 leaving the country. Although general mobilisation was announced, this did not mean that all men were to be drafted into the Armed Forces at the same time. In accordance with procedure, general mobilisation is carried out in several waves: first, the mobilisation of the operational reserve – that is, persons who already had combat experience in the course of repelling Russian aggression in Donbas in the period after 2014 – is carried out; in the second wave, there is a mobilisation of former military personnel who did not have such combat experience; in the third wave, persons who underwent military training while studying at civilian universities are mobilised; and only then are all other persons who do not have age or health restrictions called up.

The number of volunteers traditionally falls after the first year of a war, as other European countries have repeatedly experienced before – for example, during the First World War

In February 2022, the number of people willing to join the army significantly exceeded the Armed Forces’ needs, and at that time there were queues at enlistment offices. In total, as of July 2022, the Defense Forces of Ukraine numbered almost 1 million people, most of whom were mobilised. Throughout 2022 and 2023, constant mobilisation measures were carried out to replenish losses, replacing the dead and seriously wounded. These measures also did not require excessive efforts; usually, the military commanders simply sent out a significant quantity of summonses and the number of people who appeared for them was sufficient to complete the necessary reserves. Difficulties with the recruitment of new military personnel began to arise only at the end of 2023, after the Ukrainian counteroffensive was choked off.

The main reason for the decrease in the number of those willing to mobilise was the general awareness that the war has acquired a protracted nature – that is, it can and will last for years – as well as the lack of demobilisation mechanisms. In other words, mobilisation began to be perceived as a one-way ticket, where the only way to end service is to die or become disabled. Under such conditions, joining the army entailed a practical rejection of hopes for a normal life, destroyed families, and being forced to leave one’s profession forever. After more than two years of war and without any indication of when soldiers could be demobilised, military service began to be perceived as slavery, and not as a temporary, albeit very difficult duty.

Undoubtedly, this did not change Ukrainians’ perception of the war as an existential threat, nor did it significantly reduce the country’s readiness to resist aggression, but it did reduce the number of people who are willing to join the ranks of the Armed Forces without coercion. There is nothing surprising in this, since the number of volunteers traditionally falls after the first year of a war, as other European countries have repeatedly experienced before – for example, during the First World War. With the decrease in the number of volunteers, it became clear that the system of recruiting and even registering conscripts in Ukraine was working extremely unsatisfactorily, and enlistment officers often do not even have a clear idea about where exactly potential recruits live. Mobilisation began to demand certain efforts from the government for which it was not ready, and experiments with the use of coercion in mobilisation were not always successful. The public debate about the problems facing the government has not been very helpful either.

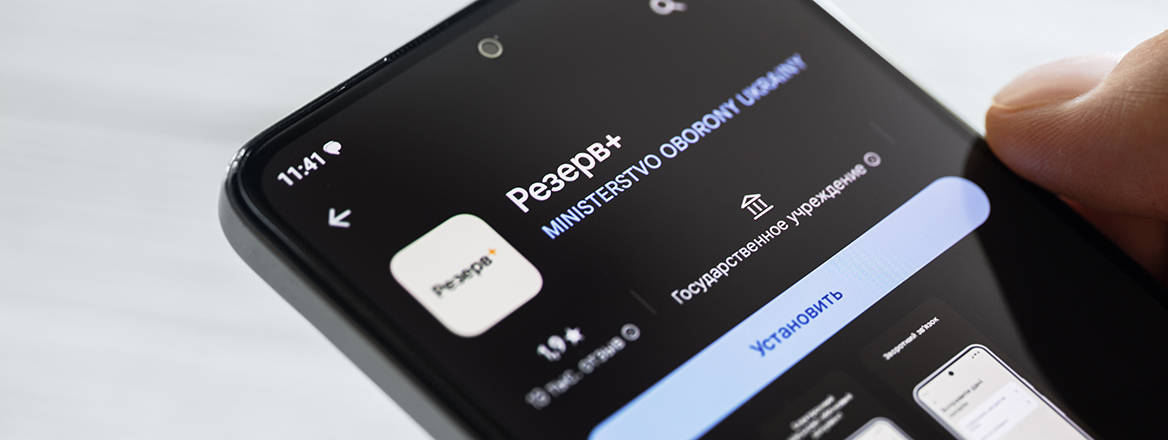

As has become a pattern for Ukraine, modern technology came to the aid of the government. Understanding the military’s inability to form a single system of accounting for conscripts, the Ministry of Defense launched the mobile application ‘Reserve+’, in which every man could update data about his location, telephone number and e-mail address, as well as clarify his military accounting specialty, rank and state of health. In the first days of the application's operation, more than a million reservists were registered; as of the beginning of July 2024, more than 2 million people had been registered in ‘Reserve+’. Taking into account the fact that before the occupation of the south of Ukraine – where several million Ukrainians live – the total number of people suitable for military service was about 6 million, as well as the fact that Reserve+ is not the only system for joining the reserve and works in parallel with the usual appeal to the enlistment offices, such results are more than satisfactory. It can be hoped that by the end of August 2024, the vast majority of reservists will be registered on the mobile application.

It must be recognised that in today's highly mechanised and hi-tech war environment, manpower without weapons and military equipment has no meaning

Despite the positive prospects of such an initiative, which has significantly improved the situation with regard to mobilisation by immediately finding several million potential soldiers, it is not able to solve the most fundamental shortcoming. The new Law ‘On Mobilisation Training and Mobilisation’ did not provide an answer to the question of when demobilisation should take place and how many years a mobilised person should serve, which in the conditions of a protracted war creates unnecessary uncertainty and reduces motivation to join the army. Solving this problem is possible by changing approaches to the composition of the Armed Forces of Ukraine – namely, increasing the total number of military professionals who must sign three-, five- and seven-year contracts, as well as establishing a maximum limit of service for those who are mobilised, which could be three years. Ukraine had such an experience in 2015–2016, when demobilisation and replacement of mobilised persons by professionals took place while maintaining the total strength of the Armed Forces. At that time, a significant number of those who had been mobilised signed contracts and continued to serve. In Russia, where the government has tried to avoid an unpopular mobilisation, recruitment into the Armed Forces is largely done through individuals signing short-term – even one-year – contracts.

At the same time, one must recognise that in today's highly mechanised and hi-tech war environment, manpower without weapons and military equipment has no meaning. Ukraine definitely needs to increase the manpower of the Armed Forces of Ukraine and replenish losses, and initiatives such as ‘Reserve+’ demonstrate that it is capable of doing this. However, the combat effectiveness of units depends not only on their number, but also on the level of provision of military equipment. There are still more than 30 territorial defence brigades in the Armed Forces, armed only with small arms and mortars, although they could be transformed into full-fledged mechanised brigades if they were to be provided with armoured vehicles, artillery, electronic warfare equipment and so on. The insufficient amount of weapons and military equipment is also a problem for regular brigades. For example, the 14 reserve brigades created by Ukraine cannot be used in combat zones due to the delay in the delivery of equipment that was promised by partners. Thus, success depends in the end not only on the improvement of Ukrainian recruiting, but also on the quality of Western logistics.

The views expressed in this Commentary are the author’s, and do not represent those of RUSI or any other institution.

Have an idea for a Commentary you’d like to write for us? Send a short pitch to commentaries@rusi.org and we’ll get back to you if it fits into our research interests. Full guidelines for contributors can be found here.

WRITTEN BY

Oleksandr V Danylyuk

RUSI Associate Fellow, Military Sciences

- Jim McLeanMedia Relations Manager+44 (0)7917 373 069JimMc@rusi.org