Brexit: A Case for British Recalibration In Relation To Asia and Africa

The Brexit vote has created an urgent need for the United Kingdom to redefine its global identity if it is to remain a leading player in international affairs. Re- assessing relationships with Asia and Africa might be a good place to start.

The British electorate has made a momentous foreign policy decision, the ramifications of which will not be fully understood for some time. But whilst the full consequences may not yet be clear, the country’s decision has already had an impact on how it is perceived – and treated – by the rest of the world. It is therefore imperative that the country starts to think about crafting a new role, adjacent to its European one, and redefining its identity in an international context. This should be built on advancing liberal ideals and values to the world, whilst seeking out new markets and opportunities and ensuring that British national security and interests lie at the heart of foreign policy.

The UK still has a number of strong cards in its hand. These include its membership of NATO, its seat at the United Nations Security Council, membership of the Five Eyes intelligence community, of the G7 group of industrialised states and the world-wide links that the Commonwealth family of nations brings, in addition to the availability of the City of London as one of the world’s biggest trading hubs and a language that is the universal mode of communication. Success however will depend on whether these advantages can be translated into a new series of international relations in a world with a growing number of superpowers.

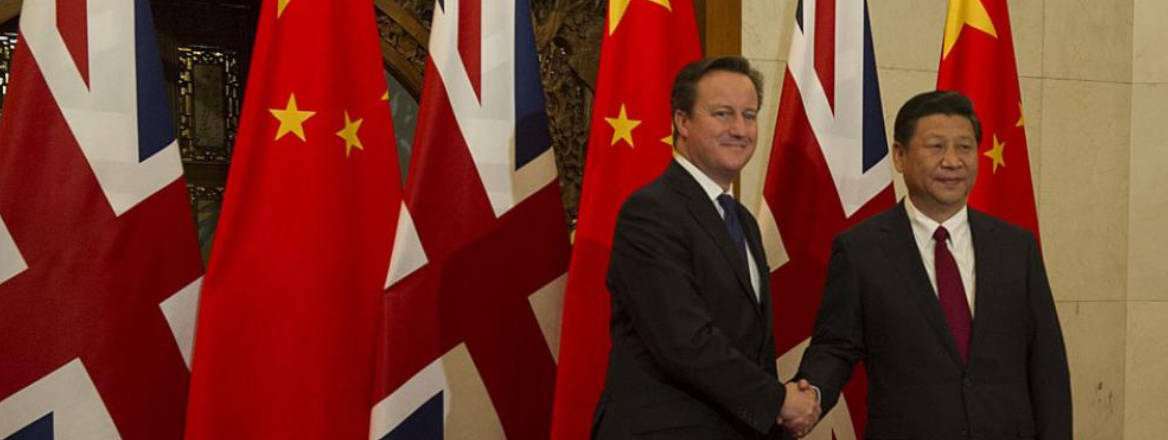

The first port of call after Europe must be Asia. Chinese President Xi Jinping’s recent visit to the UK gave birth to a ‘global comprehensive strategic partnership for the 21st Century,’ whilst during Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s recent visit, Prime Minister David Cameron told a packed Wembley stadium that ‘team India, team UK - together we are a winning combination’. Not long before the EU referendum, Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe visited the UK in order to reaffirm the strong bond between the two countries, stressing that ‘we are clear that we are stronger when we work together – both bilaterally and alongside our international partners’.

Whilst there is no doubt that the UK will now be perceived as a different power by these Asian giants, it will nonetheless still be a significant power. Its seat at the UNSC will guarantee that it will have a voice in the conversation, but the UK needs to initiate a programme of intense diplomacy and engagement to convince the world that, from its position outside the European Union, it still has a distinct role to play on the international stage.

First, it needs to ensure the message gets across that the country is open for investment and will continue to be an attractive trade partner. Asian markets reacted badly to the decision to withdraw from the EU and are still fragile in the face of a Chinese slowdown.

Second, the UK needs to find a way to strengthen its voice on crucial Asian security and political questions. Until now, the country has played a secondary role in the majority of Asia’s most difficult security questions, focusing more on its partnerships with Europe or its alliance with the United States and using them as vectors to engage with regional Asian security issues. While these partnerships will remain important, by demonstrating a deeper understanding of regional security issues the UK will show that it is not just there for mercantile reasons, but through a desire to engage, influence and support.

Thirdly, the UK needs to focus on engaging with the flow of Asian capital into bigger regional or global projects; China’s ‘Belt and Road’ vision, India’s ‘Act East’ policy and Japan’s continuing strategic engagement with its neighbours all create opportunities for the UK to engage with third countries, alongside and together with these Asian giants. This can take the form of joint investments and projects, but also the use of British relations and diplomacy to help deepen the UK’s strategic engagement with these Asian giants across the developing world.

Finally, the UK needs to peer beyond the Asian giants of today and look to the next potential rising wave: powers like Bangladesh, Pakistan, Burma, Indonesia or the Philippines are at very different stages of development, but have massive populations that will inevitably grow in size, power and eventually influence. Forging strong relations in development, trade, economics and security sooner rather than later will help to establish the UK as a relevant player at the heart of the emerging Asia.

Beyond Asia, the UK needs to also look more closely at Africa, a continent that has largely been relegated in most British government planning to the status of being either a security concern or a development project. While these issues are undoubtedly important in terms of UK engagement with the African continent, focusing on them alone risks missing significant opportunities for economic engagement. Across Africa, there is a grass roots community of small to medium entrepreneurs who are creating a new commercial climate. By finding ways of engaging with this community, helping them connect with British counterparts, as well as continuing to focus on reform, development and engagement with Asian powers as they invest in large scale infrastructure projects across the continent, the UK can successfully re-position and redefine itself globally.

It will of course be impossible to know if any engagement, financial, diplomatic or otherwise will be able to replace what is likely to be lost by the Brexit decision. But in order to ensure that the UK does not become merely an island off the coast of Europe in more than a geographic sense, there is a need for the country to move quickly and find a way to reposition itself as a power with influence and relationships that enable it to punch well above its weight. This may seem a daunting task, but it it’s not an impossible one.

WRITTEN BY

Raffaello Pantucci

RUSI Senior Associate Fellow, International Security