A New State in the Middle East? From the Kurdistan Region of Iraq to the Republic of Kurdistan

The likely result of the upcoming referendum in the Kurdish areas of Iraq will create a dilemma for the Iraqi state and foreign powers.

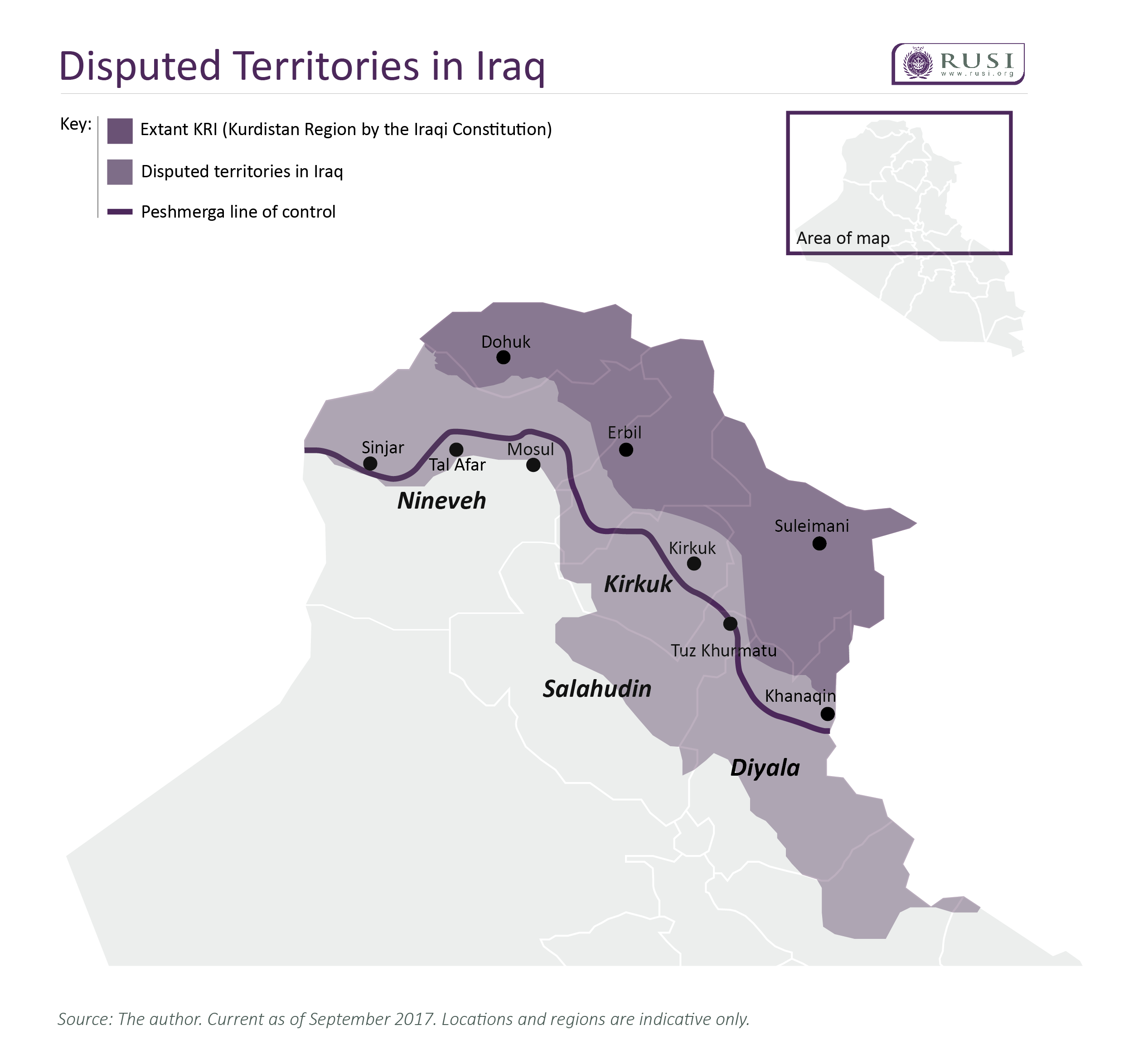

After many years of threatening to secede from Iraq, in June 2017 the Kurds announced their intention to hold a referendum, scheduled for 25 September, asking whether the Kurdistan Region of Iraq (KRI) should become independent. The referendum is to be held in the territory formally administered by the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG), and also in those areas in the ‘disputed territories’, including Kirkuk, controlled by the KRG since the summer of 2014, following the rise of the Islamic State (IS). It appears clear that the pro-independence forces will win the vote. While the end result of the referendum itself is not in doubt, there remain many questions about what happens next. How will this powerful expression of Kurdish self-determination be used by Kurdish leaders? Will they attempt to use it as leverage in Iraq, to gain further autonomy, perhaps through a confederation arrangement? Or will they attempt to turn what has been the Kurdish century-old dream of independence into the reality of a new Republic of Kurdistan?

There has been a great deal of focus upon why Kurdish leaders, and particularly KRG President Massoud Barzani, have been so keen to push for the referendum to take place, with several focusing upon the internal political problems faced by him and his circle. This paper argues that the changing situation of the Kurds in Iraq, now that the country enters a ‘post-IS’ period, presents their leaders with an array of opportunities, threats and challenges that make a secessionist initiative logical, and perhaps even necessary. The paper also considers the Kurdish secessionist agenda from the viewpoint of Western powers, in particular with regard to whether the staunchly held policy of maintaining Iraq’s territorial integrity is now appropriate, and what the ramifications of opposing Kurdish aspirations might be at a time when Middle Eastern states and other interested powers – namely Russia – may be adapting to new realities more swiftly than their Western counterparts.

Considering the wider Middle East, the positions of Turkey and Iran are also critical in conditioning the actions the Iraqi Kurds take after September; and the US, and now Russia, also have key geopolitical and economic interests that will be affected, as has Europe. There are additional reports that Sunni Arab states, including Saudi Arabia, may view a new Republic of Kurdistan as an ally in limiting Iranian influence in Iraq, at least by taking the northern part out of the equation. It could also be used to put pressure on Turkey, following Ankara’s support for Qatar. Many predictions of changes to the state system established in the years following the First World War are now potentially becoming reality. Yet Western countries, especially the US and the UK, seem reluctant to acknowledge this shift, potentially limiting their options to engage and influence the Kurdish leaders at what is a critical period.

The views expressed in this publication are those of the author, and do not reflect the views of RUSI or any other institution.