The Republican Party and US Foreign Policy: What Next?

The Republican Party’s foreign policy remains under the influence of former President Donald Trump’s ‘America First’ approach to the world. That is unlikely to change anytime soon.

Traditionally, when a US political party loses a presidential election and control of the Senate, and remains in the minority in the House of Representatives, the party elders accept the verdict of the electorate and engage in a fundamental rethinking of their domestic and foreign policies. At the same time, attractive and usually younger political personalities emerge and start auditioning in a years-long public talent competition to become the party’s new standard bearer.

This has not happened with the Republican Party after last November’s elections, at least not yet. Like so much else that explains the state of the Grand Old Party these days, the reason is former President Donald Trump.

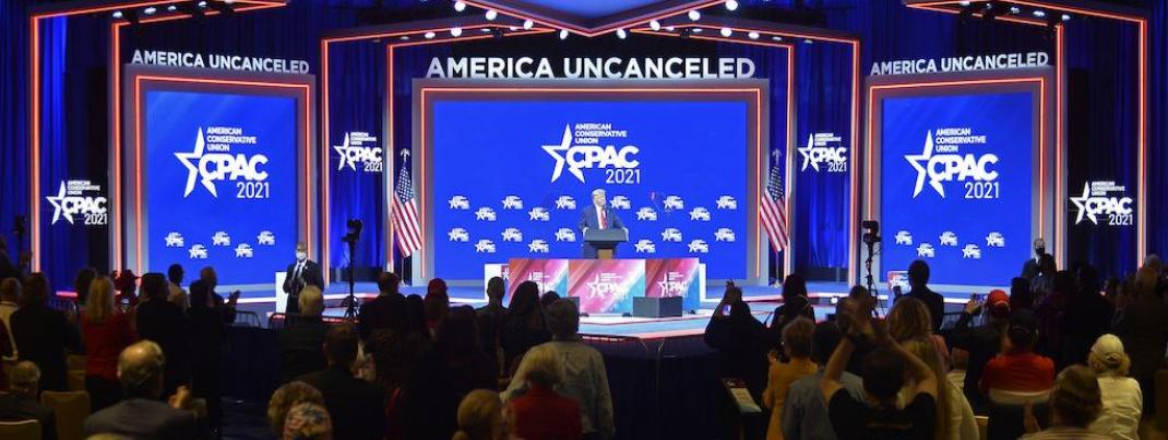

The Republican Party remains under the control of the former president. February’s conference of the Conservative Political Action Committee in Orlando demonstrated his continuing attraction to the Party’s rank and file, the ones who vote in primaries, staff campaigns and write cheques. Whether Trump will actually run for president again in 2024 matters less than the fact that the possibility of his running effectively occupies the field in the meantime, dominating the media, rousing enthusiastic supporters, sidelining aspiring leaders and hoovering up financial contributions. Politicians from across the country continue to make pilgrimages to Mar-a-Lago to receive his benediction. He still rules the Party like no other figure.

Just as the 2020 Republican National Convention did not have a platform setting out the Party’s principles – meaning that it stood for whatever President Trump said – Republicans will take their foreign policy cues from the past four years of the Trump administration and from whatever the former president now says.

A Narrower Perspective?

It was not always this way. Since the end of the Second World War, Republican foreign policy was best characterised as taking a ‘realist’ approach to international affairs. This meant support for a strong military, for working closely with allies, partners and friends around the world, for free trade, and for defending human rights and promoting democracy. There was broad consensus within the Party that the liberal world order the US helped to construct after the Second World War came at a price, but that its provision of public goods – most notably security and prosperity – was worth it because the US disproportionately benefited. Indeed, Republican presidential leadership was instrumental in building, moulding and empowering this order.

A Trump-oriented foreign policy sees a much darker, more zero-sum world. International cooperation is a ruse and a means for other countries to take advantage of the US’s gullibility and generosity; alliances are a cover for free-riding allies who don’t appreciate the US’s sacrifices and never pay their fair share. ‘The future does not belong to globalists’, President Trump declared to the UN in September 2019. ‘The future belongs to patriots. The future belongs to strong, independent nations…’.

After two debilitating and seemingly endless wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, this banner of ‘America First’ found a receptive audience among voters who believed that a less interventionist and more restrained approach to the world would better serve US interests. In that same UN speech, Trump placed the world on notice: ‘The United States … can no longer be taken advantage of, or enter into a one-sided deal where the United States gets nothing in return. As long as I hold this office, I will defend America’s interests above all else’. In the future, the US would be less generous and engaged, and more transactional and self-regarding.

This is the foreign policy framework within which the Republican Party now operates. Any deviation from an ‘America First’ approach will find a very cold reception. The Trump orthodoxy is now the Party line.

As long as they remain in the minority, Republican leaders will be defined more by what they oppose than what they support. Trump and others will oppose the Biden administration’s efforts to re-engage with Iran to limit their nuclear weapons ambitions and revive the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, which Trump had labelled as a ‘disaster’ and ‘the worst deal ever’ before he withdrew from the agreement in 2018.

Trump and others will continue to express scepticism about climate change and the wisdom of Biden having the US rejoin the Paris Accord (see, for example, Trump at the Orlando conference: ‘What good does it do when we’re clean, but China’s not, Russia’s not, and India’s not?’). They will continue to attack Democrats who do not want to build a border wall with Mexico and who seek to loosen immigration restrictions.

Key Foreign Policy Issues

Two other foreign policy issues that deserve close attention are Russia and China. Historically, Republicans have been hard-nosed about the Soviet Union (it was a given in US politics that ‘no one ever lost a vote by being too tough on the Russians’). But during the Trump administration, the president seemed to interpret any criticism of Russia as a proxy for raising the issue of Moscow’s interference in the 2016 presidential election and thus questioning the legitimacy of his victory. It will be interesting to see if Republican leaders now feel free to speak out more about Vladimir Putin’s dictatorial ways and Russia’s ongoing interference around the globe.

The other issue is China, which presents the US with its most complex and consequential challenge. President Trump’s December 2017 National Security Strategy stated that we were living in an era of ‘great power competition’, and although it grouped Russia with China, it was clear that its primary focus was the latter.

If we fast forward four years, there is now far more bipartisan agreement that China presents a comprehensive military, commercial and political threat to the US. Beijing’s provocative military actions in the South China Sea and mercantilist trade policy had long prompted growing concern, but its more recent coverup of Covid-19, its crackdown on democracy in Hong Kong, reports of genocide against the Uyghurs in Xinjiang Province and the use of academic exchanges for espionage have been an inflection point. Public approval of China in the US is the lowest it has been in more than a decade.

But bipartisanship only goes so far. It is easier to see Republicans working with Democrats to punish China in the next few years – for example, on trade or human rights – than to enlist China’s support on climate change or nuclear nonproliferation efforts.

It falls to the Biden administration to manage the tension between the Republican Party’s ‘America First’ impulses and its own more international approach to the world. A theoretical sweet spot where both parties might collaborate is foreign policy issues that benefit the US worker, such as trade. In an early February foreign policy address, President Biden declared that ‘every action we take in our conduct abroad, we must take with American working families in mind’. Even Trump could agree with that.

Mitchell B Reiss served at the National Security Council and State Department in three Republican administrations, where he was Director of the Office of Policy Planning and held the rank of Ambassador. He is currently advising universities and other not-for-profit organisations in the US and the Middle East.

The views expressed in this Commentary are the author's, and do not represent those of RUSI or any other institution.