Nearly Forgotten but not Gone: The Legacy of the UK’s Retired Nuclear Submarines

Britain’s difficulty in dismantling its retired nuclear submarines represents a classic lesson in the benefits and risks of deferring ‘non-urgent’ spending in the defence sector.

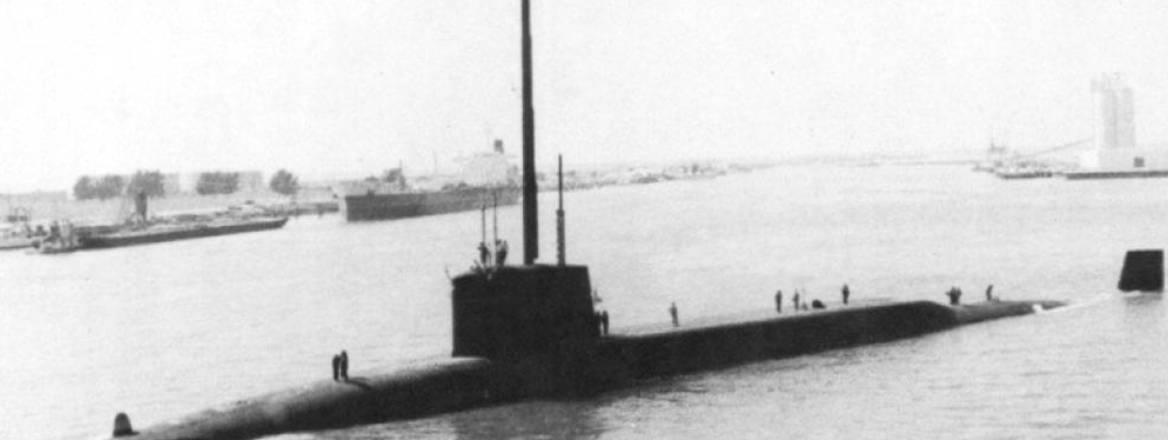

Britain’s parliamentary financial watchdog, the National Audit Office’s (NAO) report on the Ministry of Defence’s (MoD) snail-like progress on de-fuelling and dismantling of the country’s retired nuclear submarines exposes the MoD’s long history of failure to prioritise this matter and its preference for spending a modest amount for many years rather than larger sums in the near future. As a consequence, the MoD has 20 old submarines in storage at Rosyth and Devonport with nine at the latter site still containing their nuclear fuel; the 20 include the original Polaris boats which left service in the 1980s.

Although the MoD established disposal as the final phase in its formal acquisition life cycle as early as 1998 in its Smart Procurement Initiative, this does not appear to have had much impact in the submarines area: 20 years later the MoD does not know how long disposal will take or what it will cost.

Programme Management

The disposal of submarines involves a series of stages, all of which are subject to stringent safety and security regulations. In succession, they comprise the following activities:

- On retirement, submarines are fitted out for safe storage within specified infrastructure at Devonport or Rosyth, and then subjected to periodic inspections (and re-painting every 15 years) which require them to be taken out of the water. With the Trafalgar-class attack boats being replaced by Astute vessels, accredited storage space is becoming scarce.

- The nuclear fuels need to be removed from the reactor using special equipment with the boats out of the water. In 2004 the regulatory authorities ruled that the facility did not meet the latest standards (p. 12) so the refuelling facility at Devonport needed major changes. Partly because the MoD diverted resources elsewhere, the new infrastructure was not ready as envisaged in 2012 and will not be operational until 2023 at the earliest. Commercial discussions with Babcock on the completion and management of the de-fuelling facility are underway and not settled. Also Babcock’s skilled resources dealing with nuclear fuel have had to be diverted to the unexpected need to re-fuel HMS Vanguard, currently at Devonport.

- Medium-level nuclear waste including the reactor pressure vessel must then be removed from the submarine. HMS Swiftsure is being used as a ‘prototype’ to explore in detail how this project should be implemented although vessels from other classes might need a different approach. A site for the storage of this waste has been chosen (in Cheshire) but there is no contractual arrangement in place yet for the safe transport of this material. An MoD appeal for notice about this task did not bring any viable private sector interest.

- Once rendered safe, the submarines are to be broken up and ‘recycled’, and the MoD is looking for British firms which might take on this work. Security considerations mean that only UK citizens can be used.

In short, there are significant gaps in the ministry’s work-breakdown structure and its contractual arrangements to deal with the issues.

Money

The report is clear that the delays plus external interventions including changes to the regulatory framework have caused cost increases but neither the NAO nor the ministry’s own annual report on its accounts make clear what the MoD plans to spend over the next decade – that is, the period covered by the Equipment Plan. The MoD’s accounts show expenditure of around £236 million in 2017/18 and anticipate spending of just under £200 million a year in the four years following. Given that the NAO said that the MoD had spent just £500 million over the previous three decades on this matter, spending is clearly rising. However, the only other numbers provided are for a 120-year period (£7.5 billion for submarine decommissioning alone and £10.2 billion for MoD nuclear decommissioning overall). Moreover, these numbers have been generated using the MoD’s accounting processes involving estimates of interest rates and inflation and are not specified at current prices. To assess affordability and impact on other areas of defence spending, the 120-year figures are not helpful.

Commercial Relationships

The NAO reminds us that the MoD is reliant on a single supplier, the dockyard owner Babcock, for the delivery of this work but does not explore the question of incentives on the company actually to push ahead with decommissioning and get the number of submarines in long-term storage reduced. It may be that the current situation in which the company gets to manage the long-term storage of the maximum number of vessels possible suits the firm well from a financial and employment perspective. On the other hand, the precise responsibilities and the elements of work that are being done on a fixed cost or cost-plus basis is not known. The NAO does not explore the risks being borne by the contractor.

A situation in which the MoD relies on a single supplier for a vital set of services requires that the customer-supplier relationship is very cooperative. There were rumours last autumn that there may be problems in this area.

Conclusion

At some point, the sale of the specialist nuclear dockyards could serve as a classic ‘lessons-learned’ case study into the benefits, risks and mechanisms of outsourcing in defence but at present there are too many known unknowns as well as unknown unknowns for any external body to do rigorous work.

In general, the MoD appears to have been extremely open with the NAO during this inquiry which suggests that the department would like a little more sunlight shining on the programme. While the MoD must anticipate a rough ride from the Public Accounts Committee when it considers the NAO’s report, the press coverage of the NAO’s findings should mean that the ministry gives increased and constant effort to easing the situation and that customer-supplier relations will be a source of external interest.

Trevor Taylor is Professorial Research Fellow, Defence, Industries and Society at RUSI.

The views expressed in this Commentary are the author's, and do not necessarily reflect those of RUSI or any other institution.

WRITTEN BY

Trevor Taylor

Professorial Research Fellow

Military Sciences