Keep Your Friends Close and Turkey Closer: EU–Turkey Relations

An agenda for engagement with Turkey, warts and all.

As European countries gear up for the Special European Council on 24 and 25 September, relations between the EU and Turkey have hit rock bottom. Ankara’s decision to pull back ‘for maintenance’ the Oruç Reis research vessel – whose presence in contested waters heightened the current tensions – is positive, but the risk of further punitive measures against Turkey now depends on internal EU negotiations.

Rich but Problematic Findings

While 2020 became the year of public confrontations in the Eastern Mediterranean, 2019 can be labelled as the one of silent preparations. After signing commercial exploration and production contracts with Total, ENI and Novatek in 2018, seven energy ministers from Cyprus, Egypt, Greece, Israel, Italy, Jordan and the Occupied Palestinian Territories signed the East Mediterranean (Eastmed) Gas Forum in 2019. Five gas fields in a radius of 150 km today contain around 90 trillion cubic feet (tcf) of natural gas reserves, the equivalent of six times the annual consumption of the US. The reserves are located in Cypriot, Egyptian and Israeli maritime exclusive economic zones (EEZs), with the Israeli and Egyptian discoveries already in production.

This year, ExxonMobil, Total and ENI are conducting further exploration missions to find more gas in order to diminish high investment costs linked to drilling, processing, export infrastructure and transportation. The expensive endeavours are needed to either pipeline gas to Europe or transport it to existing processing and liquidation plants in Egypt and Israel. This year, Cyprus joined the game of potential exporters when signing a deal to build a liquified natural gas import terminal by 2022.

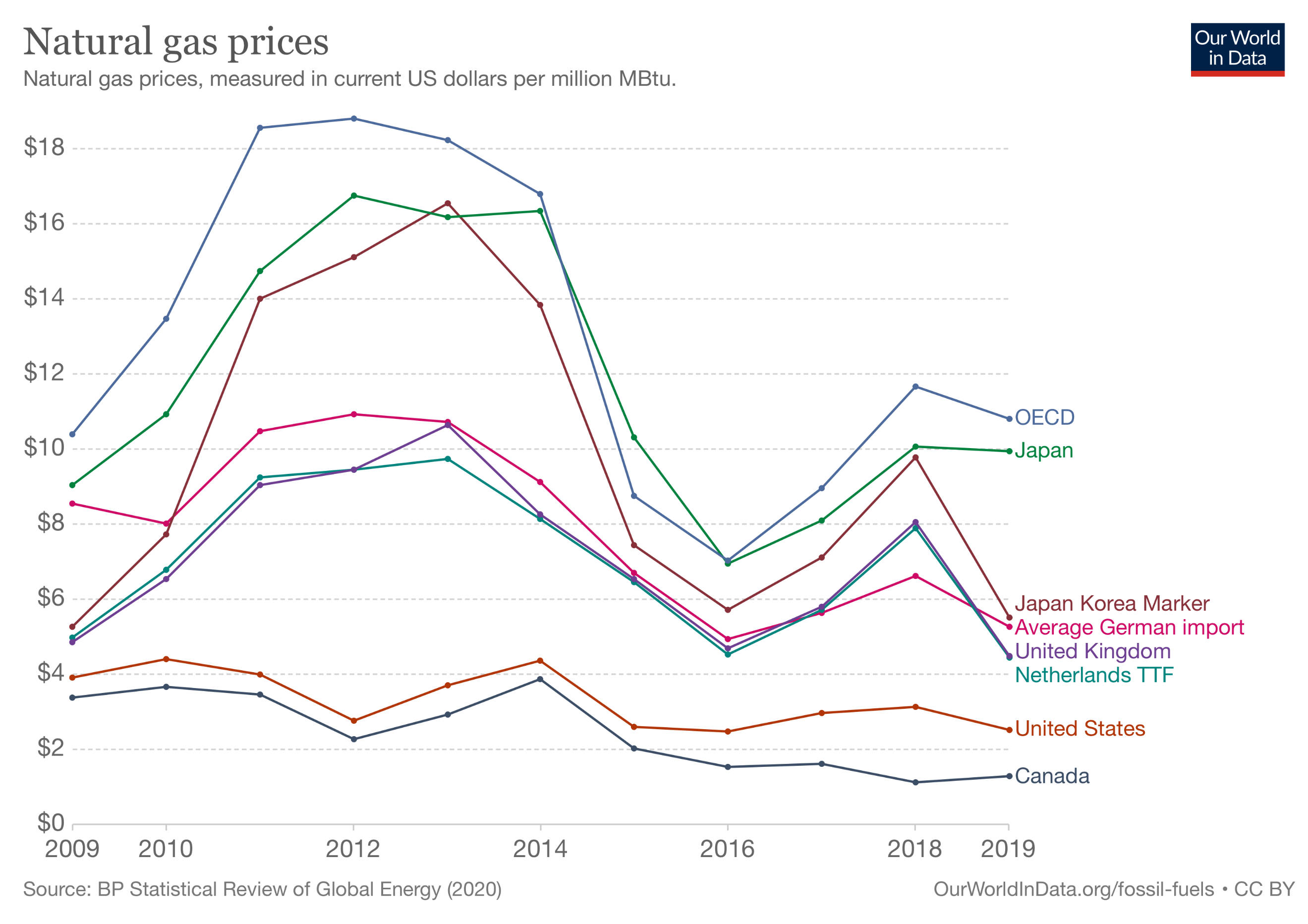

A degree of uncertainty remains about regional gas discoveries and their financial feasibility. This is fuelled by ambiguity concerning international prices (for example, fluctuations and decline) and the viability of exportation to new markets.

Figure 1: Natural Gas Prices

An emblematic example of uncertainty is seen in discussions about how to transport existing and new discoveries to consumers. On one side, a proposed underwater Eastmed Pipeline (for example, from Cyprus through Crete to Italy) could transport future gas discoveries to Europe. On the other hand, an alternative option is to expand existing (or build new) regasification plants along littoral states in the region. Both have their problems; the latter being very expensive, the former politically toxic.

Aside from this, the project will also have to pass through non-delineated waters, which are disputed by Turkey. According to Article 87 of the UN Convention for the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), the building of underwater pipelines in other countries’ EEZ is fundamentally acceptable. But despite this clear legal framework and several neutral suggestions for better maritime delineation, the reality remains that Turkey is not a signatory to UNCLOS and rejects international arbitration. In addition, Ankara continues to engage in seismic and drilling activities off the coast of Cyprus and Greek islands. Ankara’s argument is that the island’s maritime borders and EEZ should be considered the ‘shared property’ of both sides of the island until reunification is negotiated. But that overlooks the fact that Turkey illegally invaded and occupied Cyprus in 1974 and remains the only country in the world to recognise the northern part.

Does this make the current Turkish position entirely incompatible with its neighbours? Yes, although one has to take into account the past two decades of history. Take, for example, the failed 2004 UN plan, where Greek Cypriots voted against arguably the best shot at peace and Cypriot reunification (Turkish Cypriots voted in favour). It is also important to contextualise the Eastern Mediterranean with regards to Europe’s energy plans in the late 2000s. The EU’s flagship energy diversification project, known as the Southern Gas Corridor, was meant to increase the volume of natural gas from Azerbaijan, while adding extensions from Iraq (125,5 tcf reserves) and Iran (1127,7 tcf reserves). Later, this policy became indirectly complementary with the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) ‘Iran Deal’, while improving Greek–Turkish–Italian relations, as all three would become major transit countries.

Figure 2: Southern Gas Corridor

Multiple factors derailed this ‘grand bargain’ engineered by the Obama administration, including the election of Donald Trump and Turkey’s increasingly revisionist policies with regards to its neighbours and a controversial policy of 'Islamist support' to non-state actors (for example, the Muslim Brotherhood and Hamas).

And What Does This Mean for EU–Turkey Relations?

The optimal approach should be a careful balancing act confronting Turkey not only with rejection, but also with innovative engagement options and institutionalised re-engagement, based on the following considerations:

- Over 50% of Turkey’s foreign direct investment comes from the EU, and both remain deeply intertwined economically. Turkey is part of European supply chains and is cemented to the EU Customs Union, as one of the few non-EU countries in the world. Trade volumes and the number of intertwined banking systems remain high, despite recent restrictions on arms exports. Examples of shared challenges which are practically unsolvable without EU–Turkey cooperation include illegal migration flows, regional conflicts, and broader security concerns linked to radicalisation.

- If the EU wants to provide a balancing role between Washington and Beijing to reduce global tensions and benefit from Asian trade, then serious policy cooperation with Turkey must be considered inevitable. Apart from Russia, Turkey is the only country with a land connection between Europe and Asia.

- The Turkish EU accession process is dysfunctional and breeds distrust on both sides. Turkey does not abide by the Copenhagen Criteria (such as democracy), perhaps due to the lack of incentive to reform, as France is known as an eternal obstacle for Ankara’s accession bid. Topped with the fact that many European voters have moved further to the right, this simply makes accession unworkable. Logically, it breeds mistrust since it is built on unworkable conditions and incentive mechanisms.

- Major cities like Brussels, Paris and The Hague are home to large and growing Muslim populations, representing between 10% and 20% of their inhabitants. Turkey could play an important role in the broader search for the promotion of a ‘European Islam’.

Taking into account these considerations, an improvement in EU–Turkey relations will necessitate concessions on both sides. The current German presidency of the EU provides a solid starting point for such efforts, since Berlin has shown itself to be a trusted partner in negotiations with Ankara. Indeed, the upcoming five rotating presidencies of the EU are also likely to support Turkish re-engagement along those same lines, and even France (which holds the presidency in 2022) could support re-engagement, provided that the accession process is replaced with a new and institutionalised framework of equal and special partnership, which takes into account a broader security perspective.

A Future Partnership

Such a partnership should be based on the following recommendations:

- The EU and Turkey should open negotiations to fully liberalise the Customs Union, which must include services and agricultural goods. The conditions of such an economic reform process must include judicial independence, media freedom and the reinstatement of parliamentarian immunities, including the release of notable political opposition figures. The question of visa liberalisation and transport policy should also be included.

- Key EU member states and Turkey should set up working groups to discuss policy and co-dialogue with moderate elements of Islamist groups including the Muslim Brotherhood.

- The EU, through the External Action Service and Directorate-General for International Cooperation and Development, should allocate funding towards governmental cooperation and civil society and/or business projects tied to improving Turkic relations (for example, the Turkish Council) within the context of the EU’s connectivity and Central Asia strategies.

- The EU and Turkey should start preparing for the eventual replacement of the accession process. A new framework should start with Customs Union reform, drawing lessons from existing studies, exchanges and interviews conducted by international institutions, think tanks and trade associations. Such a framework will allow for new thematic policies of shared interest to be included (such as migration, conflict resolution, security and other priorities).

- The EU should increase funds for Turkish civil society and student exchange programmes, as a forthcoming study by the European Neighbourhood Council and the Centre for Public Policy and Democracy Studies recommends. The study is based on interviews, in which Turkish students showcase high levels of appreciation for European democracy, mobility and prosperity. Diminishing cultural or educational ties between the EU and Turkey would be a loss of decades of youth investment, which is now showing positive results among new and urban generations.

If all this seems too much or too optimistic, just imagine what Greek borders, economic interests and national security would look like if Turkey were to cement its revisionist policies and leave NATO. So, for those that consider Turkey a partner, the message should be clear: engage, deter and always talk. Keep your friends close and Turkey closer.

Samuel Doveri Vesterbye (@Samuel_Jsdv) is Managing Director of the European Neighbourhood Council, a Brussels-based independent think tank researching the European Neighbourhood Policy.

The views expressed in this Commentary are the author's, and do not represent those of RUSI or any other institution.