How the current pandemic may have an impact on Africa’s relations with, and attitudes to, China.

Stepping back from the day-to-day predictions and prognostications about coronavirus, two things are of longer-term interest concerning the politics of recovery in Africa:

- First, internally, what will be the effect of the crisis on African governments and, particularly, on the relationship between the state and citizens?

- And second, externally, how will the relationship between Africa and other powers – specifically China – alter in the aftermath?

On the first question, the immediate answer depends in part on who appears to have done better in managing the crisis. This understanding is influenced invariably by the availability of information. If China has – or is perceived as having – done better than the West in managing the crisis (and we probably will never know entirely), this could embolden calls for a more powerful and authoritarian state and centralised administration.

There are plusses and minuses for African leaders of this outcome.

Following more closely a China model offers the prospect of more efficient delivery without the bother of managing the politics of the economy. Coronavirus and the lockdown enables statists to display their power and prowess – one only has to look at the instances of bully-boy enthusiasm of the South African National Defence Force in cracking down during the lockdown.

Many African leaders might like the idea of the Chinese system because it offers the prospect of staying in power and making money, rather than because of the development advantages of an efficient, centralised state.

But democracy protects leaders and citizens. The Nirvana of relatively unobstructed, unfettered power does not provide the constitutional and institutional safeguards for leadership. Unlike the Asian experience, post-colonial African history saw a slide into militarism, autocracy and incessant instability, not least because the government lacked the competition and competency to deliver development.

In a vicious cycle, this is because the state is weak and fragmented. It is one thing to mobilise against a common enemy (coronavirus) or for a short-term national goal (the World Cup); it is another to keep this machinery up, running and motivated for the longer term, not least because it is expensive.

Statist overreach by African governments – mimicking the developed world’s response in a developing world reality on behalf of elites – can only have dramatic and negative economic consequences. These will, sooner rather than later, inevitably have a political impact. Populism thrives in situations of dearth and excess, and desperation.

It is also not clear where the emergency anti-coronavirus provisions end and the benign development state supposedly takes over. African history suggest that this authoritarian path is invariably costly and fraught with personalised, fragmented interests. The benefits of this path depend, also, on the flow of external capital, skills and technology. Yet the dilution of democracy suggests that investors will be less forthcoming absent constitutional and legal safeguards, and donors are less likely to invest beyond humanitarian assistance.

The political resilience of African citizenry also might well surprise in this regard. Africa is not China. African democracy is not a system which was once upon a time benevolently handed out by leaders; it is the system favoured by the vast majority of citizens given the previous experience. And its freedoms have been hard fought for in most instances.

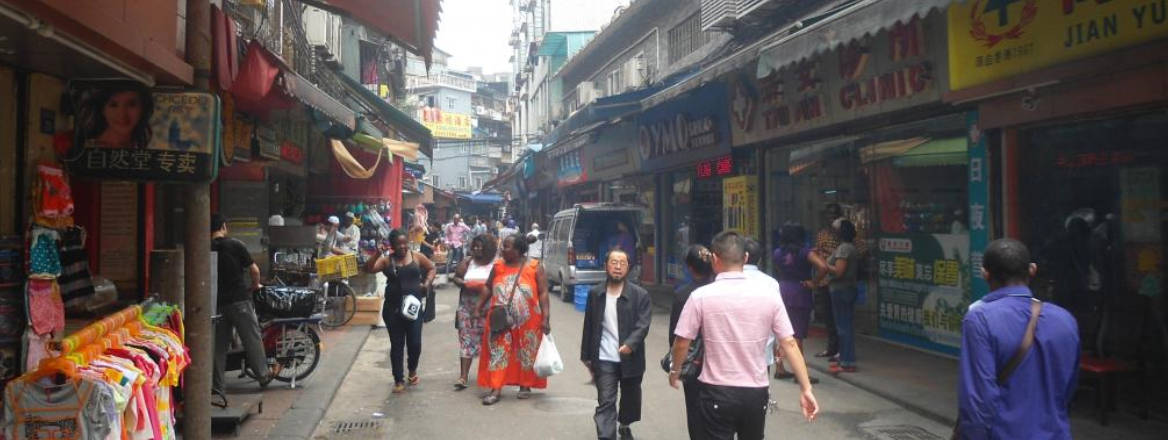

The answer to the second issue in part depends on the outcome of the first, and to the nature of global engagement post-coronavirus. China might well face other areas of push-back, not least given the allegations of the poor treatment of Africans in China during the coronavirus pandemic. Also, a surge of other sources of debt might shift attention away from China as a source of capital.

Increasing differentiation by external actors based on governance delivery and democratic norms is probably not in China’s interests. China has thrived across Africa precisely because there was little obvious monetary advantage in improving governance. A step change in debt flows to Africa based on a ‘freedoms’ means-test’ is what Africa’s performers and their citizens want and need.

The question is: Can the West offer this disaggregated alternative?

Greg Mills heads the Johannesburg-based Brenthurst Foundation.

The views expressed in this Commentary are the author's, and do not represent those of RUSI or any other institution.