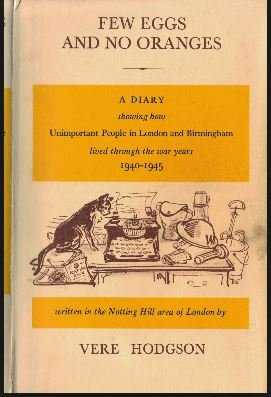

Vere Hodgson’s diary of living through the Second World War in London is subtitled ‘A diary showing how unimportant people in London and Birmingham lived through the war years 1940-1945’.

At the time Hodgson was living and working in the Notting Hill area of London; she was a social worker for a local charity before the welfare state in the UK was created and, as Hodgson herself wrote in the foreword, ‘the need was very great’. Vere Hodgson’s wartime diary was not published until 1976: it’s a copy of this first published edition that is held in the Library at RUSI. Leonard Mosley, the British journalist, historian, biographer and novelist, had quoted from her unpublished diary in his 1971 bestseller, Backs to the Wall: The heroic story of the people of London during World War II and reviews of Mosley’s books praised her contributions as ‘the richest mine’ (The Times Literary Supplement) of moving and ‘rewarding sources’ (New Statesman).

Winifred Vere Hodgson (1901-1979) was born in Edgbaston, Birmingham and read History at Birmingham University. After this she taught at the Poggio Imperiale girls’ school in Florence, which Mussolini’s daughter attended, and later at a school in Folkestone. From 1935 she helped to run a local charity in Notting Hill Gate, the Greater World Association Trust based at The Sanctuary, 3 Lansdowne Road, Holland Park. She had become interested in social work rather than continuing with ‘the academic atmosphere in which [she] had always lived’ and her welfare work was important enough for her not to be called up during the war. She lived near to Lansdowne Road, in Ladbroke Road, and this combination of circumstances meant that her wartime diaries describe a relatively close community set against not only The Blitz but the wider context of the war and the Association’s local, national and international connections and activities. Her wartime diaries are also written with warmth, humour and compassion whilst documenting the strain and anxiety of constant bombing, worry about friends and family, supporting others in need and the scarcity of essentials – especially food.

She began her diary on Tuesday 25 June 1940 after ‘the first air raid of the war on London’ as she describes the events and her responses to it the following morning: fear as she shook all over; being reprimanded for forgetting to black out the skylight; collecting together for shelter with her neighbours; how the’ moon was clear and lovely’; and of listening to the news of the war on the radio the following day. It is startling to be reminded that there was a first time for the experiences that we have since seen replayed over and over in fiction and fact, in drama and documentary. This continued for five years and in her entry for Tuesday 2 January 1945 the weariness caused by the bombing comes through: she hears a ‘Rocket drop’ and registering ‘strong disapproval’ goes back to sleep.

Vere Hodgson prepared the diary for publication as a direct result of the writer Leonard Mosley advertising for wartime diaries for research into his book. The original is now in Kensington Public Library and it is possible to see how ruthlessly Hodgson edited it for publication. Yet she did not use hindsight to rewrite, or re-envision, the course of the war; and as a student of literature she understood the rhetorical effect of repetition in constructing a picture of ‘daily drudgery’ faced by ‘an ordinary commonplace Londoner’. In casting herself as one Londoner amongst many she documents the progress of the war and the devastation of London and bears witness to the struggles of all that lived in London at this time.

Recently at a conference focused on the records and archives of the Ministry of Information, MOI Digital http://www.moidigital.ac.uk/, one of the participants referred to London as the front line, a comment that made the audience stop and think again about wartime London. In Patrick Marnham’s biography of Mary Wesley, central London is described as eerily quiet once many women and children evacuated to the country-side. Hodgson’s London, though, is a busy place and working and living are ‘very tiring’. More recently, historians Philip Ziegler, London at War 1939-1945, and Angus Calder, The Myth of the Blitz, later used quotes from her edited and published diary. Her diary is now published by Persphone Books who reprint neglected works by mid-twentieth century, mostly, women writers.