Today, from the front of the Royal United Services Institute (RUSI) building, you can see Horse Guards, which was once the entrance to the royal palaces of Whitehall and St James and is still in military use.

South, towards Downing Street, is the Monument to the Women of World War II, which commemorates the contribution of women to the war effort. These views recapitulate the development of the presence of women in RUSI: virtually invisible until the Second World War. In 1942 the first seven women members were admitted to RUSI, with the caveat that they were to be in uniform, an event that is commemorated in an article in the RUSI Journal, ‘Women at RUSI’ (Vol. 162, No. 6, 2017, pp. 66–68). Women, however, have been present in RUSI’s collections since its founding, whether depicted in artworks, as women artists whose work is in the collections, as patrons and supporters in fundraising, or depositing or donating items to RUSI, as well as on the shelves in the Library, as authors and subjects.

RUSI was founded in 1831 as the ‘Naval and Military Museum and Library’ in response to ongoing debate about military education and reform by Commander Henry Downes and Major General Sir Howard Douglas. These men had a significant influence on the developing museum and library because of their professional and scientific studies: Downes was a serious amateur natural historian and had amassed a collection of exotic taxidermy and ‘curiosities’, while Douglas published works of military science and was a founder of the Royal Geographical Society.

The Royal United Services Institute for Defence and Security Studies’ location is significant to its role, history and constituency. Between Banqueting House and Gwydyr House, the Welsh Office, on Whitehall it is near other significant buildings: 10 Downing Street, the prime minister’s residence; the Palace of Westminster, the seat of the UK government; Westminster Abbey; the Home Office; the Ministry of Defence; and many other key government offices. Banqueting House has an important role in RUSI’s history as it housed the RUSI Museum from 1895 until 1962, when the museum was closed, and its collections dispersed. This places it at the heart of the political and military establishments.

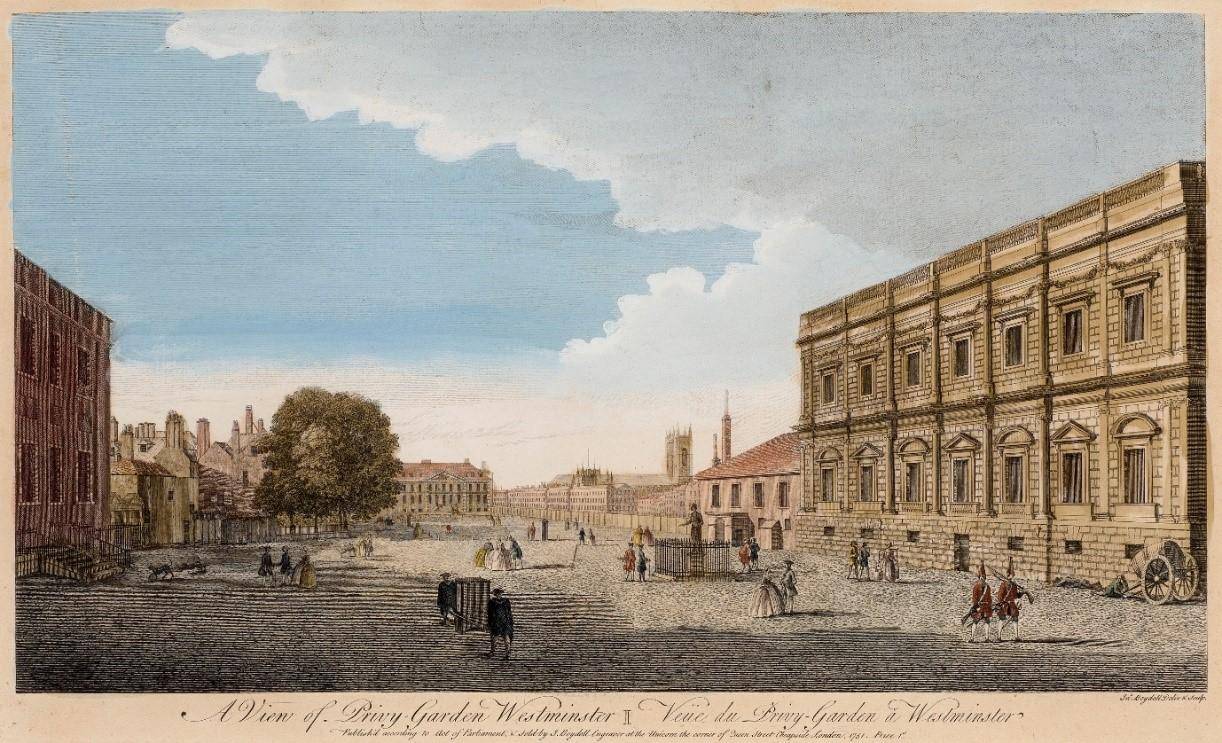

In 1833 RUSI established itself in its first home, Vanburgh House, in Whitehall Yard. Built as a residential property by the 18th-century architect and playwright Sir John Vanburgh for himself, Vanburgh House underwent building work to provide a library, model room and a natural history room. Further buildings were acquired by RUSI so that in 1849 there was also a lecture theatre. This was a pleasant and prestigious location and prime ministers Robert Peel and Benjamin Disraeli would live in nearby Whitehall Gardens. Vanburgh House looked out onto the Privy Garden, Westminster, a remnant of which now lies between RUSI and the Ministry of Defence.

In this print we can see the use of figures to provide a sense of scale, including the small figures of women, poignant reminders that women were outside the political and military establishments at this time.

The development of Whitehall Yard meant that RUSI had to move from Vanburgh House. Queen Victoria, who had granted the Institute a royal charter in 1859, provided a ‘grace-and-favour’ lease on Banqueting House as a new home for the museum and a building adjoining it was commissioned from Sir Aston Webb (1849–1930), who also built the main building of the V&A, the façade of Buckingham Palace and Admiralty Arch, among many other significant public buildings.

This portrait of Queen Victoria is important because of her patronage and because it’s painted by a woman, Eliza Anne Leslie-Melville (1829-1919). Leslie-Melville gifted the portrait to RUSI in 1909.

The museum closed in 1962 and its collections were dispersed. Notable destinations for some of the collections include the National Army Museum, the Imperial War Museum, the National Maritime Museum and the Glenbow Museum, Calgary. Women were able to visit the museum as guests of members until 1895, and subsequently by paying for entry. Throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries women were also patrons and supporters of the museum, and the guardians and protectors of the legacy of fathers, husbands and brothers. The contributions of women at times of conflict had featured in the RUSI Journal from the Crimea onwards, with the museum holding a collection of Florence Nightingale relics. Deposited by her family, this collection of memorabilia is now in the National Army Museum.

The roles of women in times of conflict throughout history is implied by this print of the Loyal Associated Ward and Volunteer Corps of the City of Westminster at the time of the Napoleonic campaigns.

This image, with tents in the background, shows well-dressed women, which probably places the image as one of the camps in Hyde Park established before embarkation. These camps became visitor attractions, but it also invokes the idea of women as camp-followers, the women that became the cooks, nurses and bottle-washers and those who were wives, mistresses and prostitutes.

The museum card catalogue, which survives in the archive, has annotations indicating how the collections were dispersed, and is an important primary source of evidence of women as patrons and supporters in the listings of who deposited or donated items to RUSI. The Wolseley Collection, donated by Sir Garnet Joseph Wolseley’s widow Lady Louisa Wolseley, was a prime example of such bequests. Wolseley was one of the most important military thinkers in the Victorian British army. Rising to a position of prominence, his military service and reforming zeal eventually earned him the title of 1st Viscount Wolseley. He was a rare creature in the Victorian military establishment – a man promoted thanks to merit, not money or credentials earned at the Staff College. In 1895 he became Commander-in-Chief. He continued to push for modernisation, professionalism and greater resources for the army. The Wolseley Collection is now held by the Glenbow Museum in Calgary. In the RUSI Library there is a copy of the 1922 ‘The Letters of Lord and Lady Wolseley, 1870–1911’, which helps provide a portrait of the woman who was determined to make a public memorial to her husband in this way.

The War Artists Advisory Committee (WAAC), established at the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939, sought to capture the effects of war by appointing official war artists. The WAAC was dissolved in December 1945 and a ballot was held for the distribution of the remaining artworks to museums and galleries across Britain and the Commonwealth. In 1947 RUSI received four artworks, two of these record the work of women in the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force (WAAF) and the Women’s Royal Naval Service (WRNS).

Dame Laura Knight has a long and distinguished career as an artist and her success in the male-dominated British art establishment paved the way for greater status and recognition for women artists. In 1936 she became the first woman elected to full membership of the Royal Academy since its foundation in 1768. This beautifully detailed portrait of two WAAFs on duty at Biggin Hill aerodrome is now an iconic image of women at work during the war and a WAAF’s uniform, along with a gas mask, as seen in this portrait, are represented in the images on the Monument to the Women in World War II on Whitehall.

The contribution of the WRNS is represented in this portrait.

The presence of women in print is substantial too, with highlights including first editions of The Letters of Gertrude Bell and Few Eggs and No Oranges by Vere Hodgson. Gertrude Bell explored, mapped and was influential to British imperial policymaking in Greater Syria, Mesopotamia, Asia Minor, and Arabia. She played a major role in establishing and helping administer the modern state of Iraq, where she made her home, and was crucial to the founding and development of both the National Library of Iraq and the Iraqi Museum. Vere Hodgson was a social worker in London during the Blitz from September 1940 to May 1941, when she kept a diary, later published as Few Eggs and No Oranges, and in which she recorded the experiences of ‘unimportant people’ on the Home Front.

Alongside social and cultural change women have become increasingly visible in RUSI, just as they are elsewhere in the political, military and research environments. Today, 41% of staff are female and Dr Karin von Hippel became RUSI’s first female director-general in 2015. She joined RUSI after serving for nearly six years in the US Department of State as a Senior Adviser in the Bureau of Counterterrorism, then as a Deputy Assistant Secretary in the Bureau of Conflict and Stabilization Operations, and finally, as Chief of Staff to General John Allen, Special Presidential Envoy for the Global Coalition to Counter-ISIL.