On the 75th anniversary of the D-Day landings, RUSI and YouGov have conducted a special opinion poll to assess current public attitudes to the event. The poll indicates that only half of Britain knows the significance of D-Day, a source of irony amid today’s polarised politics, says Sir Hew Strachan.

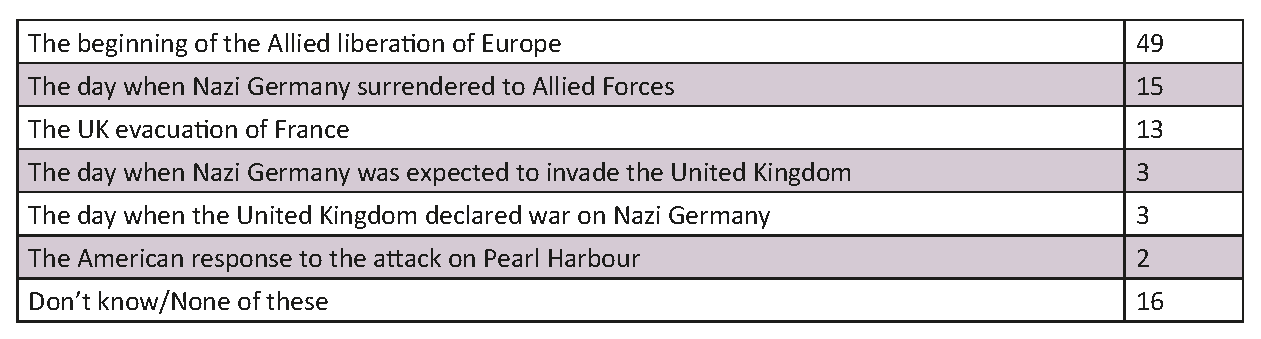

Britain’s role in the Second World War, and particularly of Winston Churchill, are in England’s national curriculum, but the wider history of the war is not. So perhaps we should not be surprised by the level of public ignorance about Operation Overlord. D-Day is, after all, a generic term for describing the opening of any military operation, and – as this polling reveals – does not help locate either the date, 6 June 1944, or the location, Normandy. Even so, the results can be read positively: the landings happened before most of us were born, but almost half the population can correctly identify their significance for the allied liberation of Europe. Any political party would greet that degree of support as portending a landslide victory.

Current politics are, of course, the context which makes this poll’s results ironic. The Second World War has become mythologised as part of a story Britain tells about itself: one which ignores the fact that this was the most destructive and costly conflict in world history, if not specifically so for the UK. For Brexiteers, D-Day is evidence of national strengths; for Remainers, it is a reminder of how intimately British and European security have been intertwined.

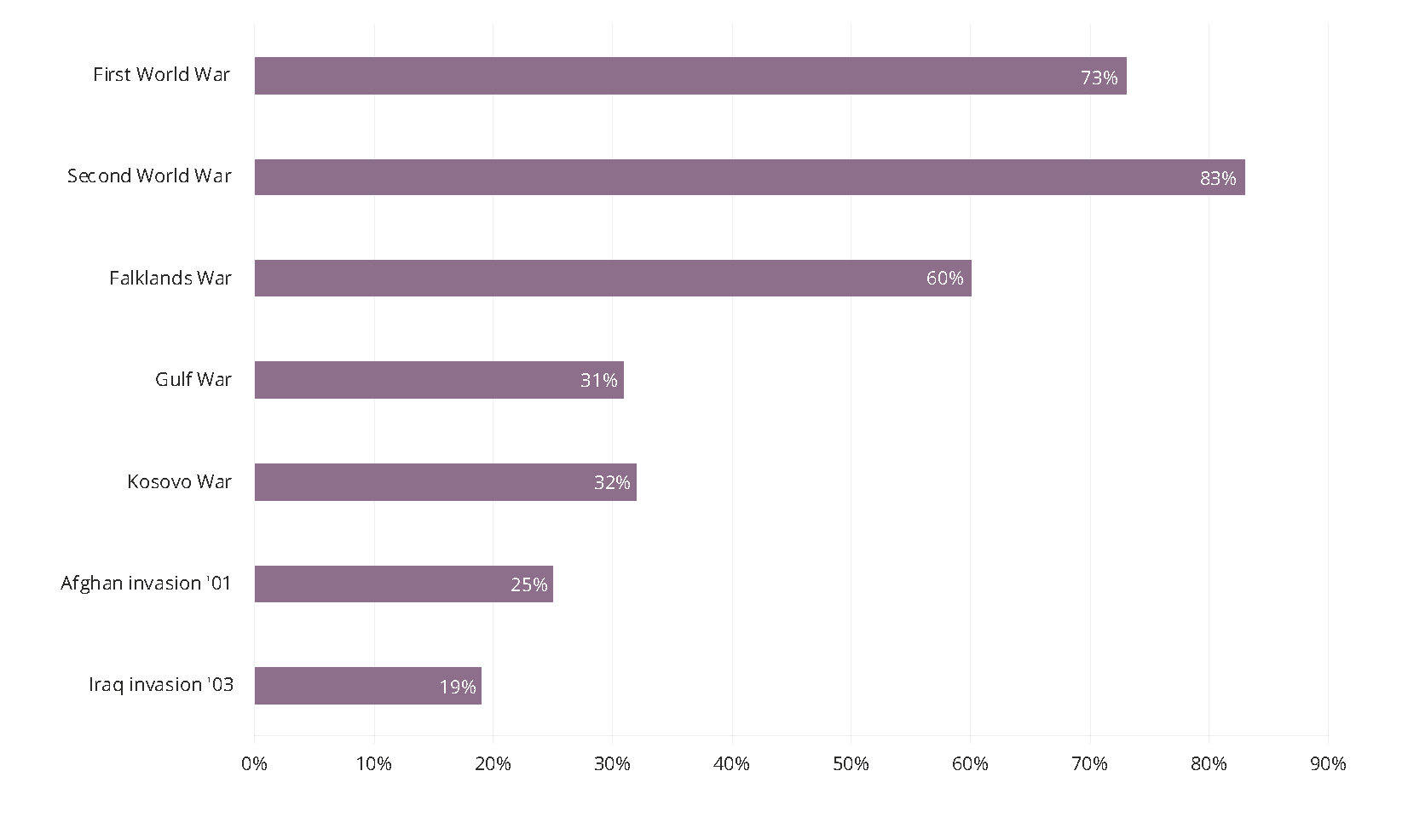

That this was a war that Britain was right to fight is endorsed by a thumping 83% of those polled. It has become the ‘good war’, with a clear division between right and wrong. What is more striking is the poll’s judgement on the First World War. Almost three-quarters think it was justified, possibly a higher proportion than at any point since 1919 itself. Is this the achievement of the recent centenary commemorations and the opportunity they provided for public education? By contrast, only 32% regard the 1999 war in Kosovo as justified, despite the humanitarian case for intervention and the absence of British casualties. It was a short war and its results have held, and yet by implication two-thirds do not accept that it was necessary.

What this poll suggests is therefore more worrying than historical ignorance; it is that the British public struggles to comprehend the complexity of current conflict. It is not clear what justifies going to war today, as opposed to in the past. The example of the First World War argues that better understanding can flow from the educational opportunities provided by public engagement.

Figure 1: Which Military Actions Were Justified? (% Saying UK Military Involvement in the Following was Justified)

Table 1: Respondent Answers to the Question ‘Which one of the following would you say best describes what the term “D-Day” usually refers to in history’? (%)

Hew Strachan

A former Chichele Professor of the History of War at the University of Oxford, the author is also a Trustee of the Imperial War Museum and a Commonwealth War Graves Commissioner. He is currently Professor of International Relations at the University of St Andrews.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s, and do not represent those of RUSI or any other institution.