Counter-Radicalisation at the Coalface: Lessons for Europe and Beyond

Europe is on a high state of alert after several terror attacks – and more are thought to be in the pipeline. So which strategy should governments adopt to address radicalisation and prevent future attacks?

As the number of planned and realised terrorist attacks against Europe continues to grow, there are increasing concerns that terrorist actors are diversifying their tactics. The subsequent difficulties this presents to efforts to interdict and mitigate attacks make the early prevention of radicalisation increasingly important. States across Europe have recognised this fact, but, despite sharing similar challenges, approaches to addressing radicalisation vary considerably. While some effective approaches have been acknowledged, there is limited consensus on what ‘works’ in practice and a lack of standardisation of activities.

This article provides insight by two local authority practitioners delivering the Prevent Strategy (known as Prevent) in the London Borough of Hammersmith and Fulham (LBHF) and the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea (RBKC). It sets out learning from five years of local radicalisation prevention activities in this part of west London (the Kensington Model) whose unique and well-developed approach could help to inform the responses of counterterrorism practitioners across Europe and beyond.

Framing the Challenge

Lone-actors, terrorist cells and large terrorist groups have, over the past five years, inflicted physical and psychological damage throughout Europe. Attackers have used machine guns, knives, trucks, bombs and cars. Targets have ranged widely from sports stadiums and Christmas markets to religious institutions. Soldiers, police officers, Muslims, Jews, and the wider public have all been specifically targeted in different attacks. Motivations have included far-right extremism, Islamism and even anarchism.This complex picture presents governments with a range of new and pressing challenges, both in disrupting plots and dealing with the repercussions. For example, security officials have openly recognised the difficulties in detecting and disrupting lone-actor attacks. This tactic is increasingly being promoted by Daesh (also known as the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria, or ISIS) and Al-Qa’ida and is recognised as having the added danger of inspiring copycat attacks. Therefore, an early identification of vulnerabilities is essential to prevent radicalisation.

Responses to Date

Considering the complexity in addressing these threats, it is sensible that some degree of local, regional and national variation to radicalisation prevention exists. However, while groups such as the European Commission’s Radicalisation Awareness Network have shared some good practice across Europe, there remains little accepted wisdom regarding the most effective activities and approaches in the long term. This has contributed to a situation where European states with similar problems are, at times, employing starkly different, even opposing, approaches.

The French government is opening twelve de-radicalisation ‘boot camps’ to house people judged to be moving towards violent extremism. In these military-style settings, participants will wear uniforms, salute the French flag and engage in highly structured educational classes, cultural lessons and exercise regimens.

Compare this with the Danish ‘Aarhus model’ of inclusion, where individuals considered vulnerable to extremism, including returnees from Syria, are supported in their inclusion in mainstream society through counselling, employment support and, potentially, accommodation.

Launched in 2012, Germany’s Advice Centre on Radicalisation helpline provides help and guidance for individuals concerned that a friend or loved one is becoming radicalised.

In the UK, the Prevent Strategy, which many countries look to as one of the most developed strategies designed to prevent violent extremism, centres on supporting individuals with tailored interventions. It does this through the multi-agency Channel Safeguarding Programme, supporting institutions and challenging terrorist ideologies. European allies are also designing new strategies, with the US Department of State and USAID releasing a Joint Strategy on Countering Violent Extremism in May 2016.

The Kensington Model

While much can be learned from comparing the relative strengths of national strategies, the experiences of practitioners delivering on the front line can also be a valuable source of insight. The London Borough of Hammersmith and Fulham and the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea are good examples, having worked in tandem for the past five years to deliver a large and unique local programme that has had tangible success in preventing radicalisation.

The boroughs have a history of extremist risk across the ideological spectrum. Several residents have travelled to Syria and Iraq to fight with Daesh, including Aine Davis, one of the infamous four ‘ISIS Beatles’, alongside another ‘Beatle’, Mohammed Emwazi (Jihadi John), from neighbouring Westminster. The Prevent team have also responded to non-Islamist referrals, such as those from the extreme far right.

However, for every individual that has been lured by the propaganda of groups such as Daesh, there are dozens of people who have received tailored help and support to live safe, meaningful lives. Indeed, at the time of writing, the team had received more than 150 unique referrals in the 2016/17 financial year. While some cases were dismissed as being not directly relevant to Prevent activity, many instances resulted in support ranging from mental health interventions to parenting classes for guardians of the impacted individuals. The team’s ability to draw on local safeguarding support has been key to the success of local Prevent delivery.

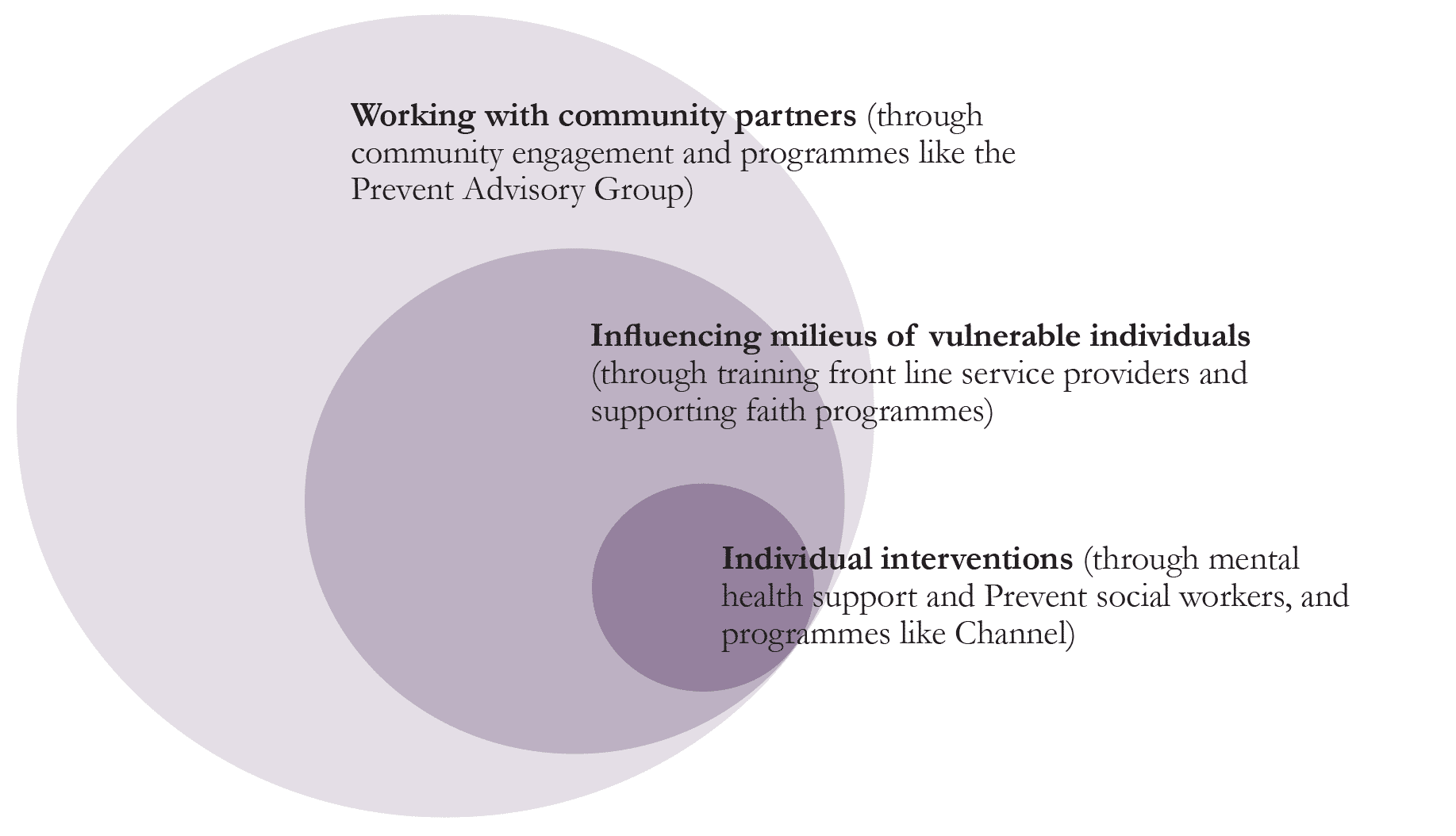

During the past five years of delivery of Prevent in the two boroughs, the team has developed a robust approach and toolkit that have been adaptive to extremist trends. It has also succeeded in securing the support of local community organisations and faith institutions in the two boroughs, despite some groups having concerns about Prevent in some parts of the country. The boroughs’ ten-point delivery plan is guided by three overarching principles that reflect widening circles of activity: first, a broad range of tailored individual interventions that draw on learning from academic insight and related policy areas; second, influencing the environments in which vulnerable individuals exist; and third, working in partnership with community organisations through a transparent and accessible local action plan.

Tailored Individual Interventions

The difference between joining a local sports team and a one-way trip to Syria can be the safeguarding support provided to a vulnerable individual. The Prevent Strategy places support to individuals at its core, through approved intervention providers commissioned by the Channel safeguarding board (for Channel cases referred to in this article, details and sources are not available due to data protection). The Prevent team in LBHF and RBKC has taken this further by providing interventions both within and outside Channel and incorporating a wider range of approaches by using the expertise of professionals in neighbouring policy areas. For instance, the boroughs employed the first Prevent social worker in the UK, as well as developing safeguarding initiatives with local voluntary and faith organisations, teachers and other local actors that understand the individual and his or her circumstances.

This approach to safeguarding vulnerable individuals allows a flexible response to all forms of radicalisation and the wide variety of drivers behind that process. While Channel handles many of the most severe or ideologically driven cases, the Prevent team’s wider safeguarding activities, using local providers and experts from neighbouring policy areas, allows work on longer-term, more nuanced cases. These have included wardship actions for families that have attempted to travel to Daesh-held territory and an individual showing an unhealthy interest in pipe bombs and sympathy for the extreme far right. The Prevent social worker used her experience to support mental health practitioners, while also offering one-to-one support to a vulnerable adult with mental health disabilities known to be linked to Terrorism ACT 2000 (TACT) offenders and who had verbalised a desire to travel to Syria to support Daesh. Other tailored support has included parenting classes provided by local community groups for the parents of affected individuals, e-safety courses for parents of children accessing extremist propaganda, and one-to-one mentoring between a vulnerable school student and his Religious Education teacher. In that case, the young man shifted from a position of wanting to leave school at sixteen to travel abroad on the advice of an unknown group of older men to rejecting that idea and completing his A-levels before going to university.

These examples illustrate a more delicate and tailored style to counter-radicalisation efforts compared with more generic or military-style boot camp methods. A stark reminder of the need for a range of intervention options was provided when, in an historic case, an individual who rejected support from the Channel safeguarding process was subsequently killed fighting with Daesh in Syria. Such cases can and must be avoided, and a wider variety of interventions and intervention specialists is part of the solution.

Influencing the Environments of Vulnerable Individuals

Understanding the broader context and settings in which vulnerable individuals work, study, socialise and worship is also vital to any long-term strategy. Tailored interventions support vulnerable individuals, but individual support programmes can be sustained only if the organisations and individuals that surround the individual understand the risks of radicalisation and contribute to safeguarding. As such, the Prevent team has spent many hours developing relationships with spheres of influence groups such as front line services, faith organisations, schools, community groups, parents, and charities.

With each of these, the Prevent team has sought to understand needs and provide support. For example, schools have been provided with training for teachers and a range of resources for use in classrooms, including lesson plans. In the 2016/17 financial year the team has trained more than 2,000 local teaching staff. Parents have been offered free thirteen-week parenting classes, and over 450 have completed the programme over the past five years. Madrasahs (Islamic supplementary schools) have been provided with a safeguarding resources toolkit, classroom management training and detailed sessions on terrorist propaganda and how to keep students safe from radicalisation.

These types of support ensure that those who interact daily with some of society’s most vulnerable individuals are aware of the risks posed by radicalisation and make sure that their institutions are ready to help them.

Working with Community Partners: Transparency and Accessibility

It has been well documented that some community organisations and faith groups have been critical or suspicious of the Prevent Strategy, in part influenced by anti-Prevent groups. Preventative strategies will be far less effective without the long-term support of communities and so the team have employed dedicated officers whose sole responsibility is community engagement. They help groups to understand how Prevent works locally and why safeguarding local people is so important, to answer questions and support them in their work. This transparency and accessibility is vital to securing close relations with the community and pays dividends in efforts to prevent radicalisation.

One example is that in December 2016 the local Prevent Advisory Group (PAG), a unique network in the London Borough of Hammersmith and Fulham and the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea, celebrated its fifth year of monthly engagement meetings with a continually growing membership of community groups and faith institutions. In those five years, the Prevent team has confronted criticism and heeded advice, and the monthly meeting is now an opportunity for local groups to co-design and co-deliver safeguarding support for individuals at risk of radicalisation. This turnaround is testament to the importance of open debate, community buy-in and a cooperative approach to Prevent delivery. PAG is now a key partner in shaping local Prevent delivery and as one member (chair of a local Muslim organisation and school governor) commented recently:

Having been a vocally critical member within the Prevent Advisory Group (PAG) from the outset, [PAG meetings] convinced me it was best for Muslim groups to engage … Prevent has evolved, learned lessons, and achieved significant strides during the last five years.

Conclusion

The work described in this article is taking place on a local level, but the lessons have wider implications. Although it is too soon to compare the success of new programmes in Europe, the Prevent approach to countering radicalisation has proven its value in supporting individuals, shaping local contexts, and securing the support of local communities. Through these three guiding principles, preventative work can make an important contribution to wider counterterrorism work across Europe, providing safeguarding to individuals and societies.

Dr David Parker

David Parker is a Postdoctoral Research Associate and Teaching Fellow in the Department of War Studies at King’s College London. His research primarily focuses on preventing, interdicting and mitigating lone-actor extremist events, as part of the EU-funded PRIME project. He also supports the strategic local implementation of Prevent in the London Borough of Hammersmith and Fulham and the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea.

Jonathan Davis

Jonathan Davis works as a Prevent officer in the London Borough of Hammersmith and Fulham and the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea. Prior to this he spent two years working in the commercial security and political risk sector.