A ‘Brexit Election’ that Shied Away from Foreign Policy

After the surprising results of the so-called ‘Brexit election’, which left the Conservative party short of a majority in Parliament, polling suggests that the British public has an increasing interest in UK foreign policy, although it feels uninformed and is increasingly divided on foreign policy issues.

Much has been said about how little Brexit was discussed during the supposed ‘Brexit election’, where one of the key reasons for holding the ballots was to give Prime Minister Theresa May both a stronger mandate on Brexit, as well as a significant majority to aid an implementation of any divorce from the EU. What is true of Brexit is even more so of the UK’s wider diplomatic, defence and trade interests, which almost entirely define the domestic choices we face.

The words of a former senior cabinet minister during this election – that ‘nobody votes for a party on what they say on foreign policy and defence’ – might well hint at why real discussion on this topic was lacking. UK political parties in general agree more on foreign policy than on domestic issues, although we are seeing a shift, both in the increasing role of foreign policy in the job description of the prime minister, and in the public’s genuine desire to be involved in foreign policy.

In a private interview one former senior diplomat commented that until recently many diplomats generally held the view that foreign policy discussion is best left to policy experts, but that growing parliamentary participation in major foreign policy decisions (such as the votes on the interventions in Syria and Libya) – as well as public interest in these decisions – demonstrates the urgent need for a broader debate. The general election suggested that this debate is still not happening.

A recent nationwide poll, carried out by the British Foreign Policy Group (BFPG) and BMG Research as part of the former’s National Engagement Program, revealed that only 38% of the (voting age) British public feel informed about UK foreign policy issues.

58% of the British public are interested in what the UK does internationally

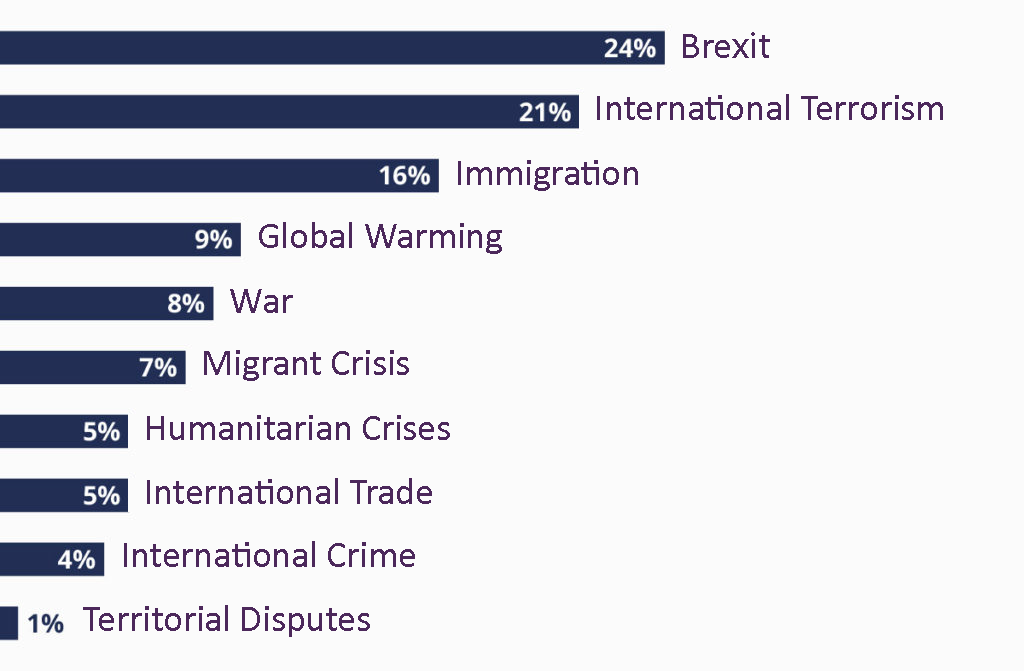

But popular involvement in foreign policy is considerable. The BFPG/BMG poll shows that 58% of the British public are interested in what the UK does internationally. As a result, government ministers may find a receptive audience should they wish to engage the public in a broader array of foreign policy debates; the idea that the public is indifferent is not supported by the evidence. During the EU referendum, the British public were asked to make a decision on one of the most crucial aspects of our foreign policy, our relationship with the EU. Brexit still remains the number one foreign policy priority for the public (as shown in Figure 1), a sign that perhaps, unlike in the past, the public may be more receptive to further foreign policy debates.

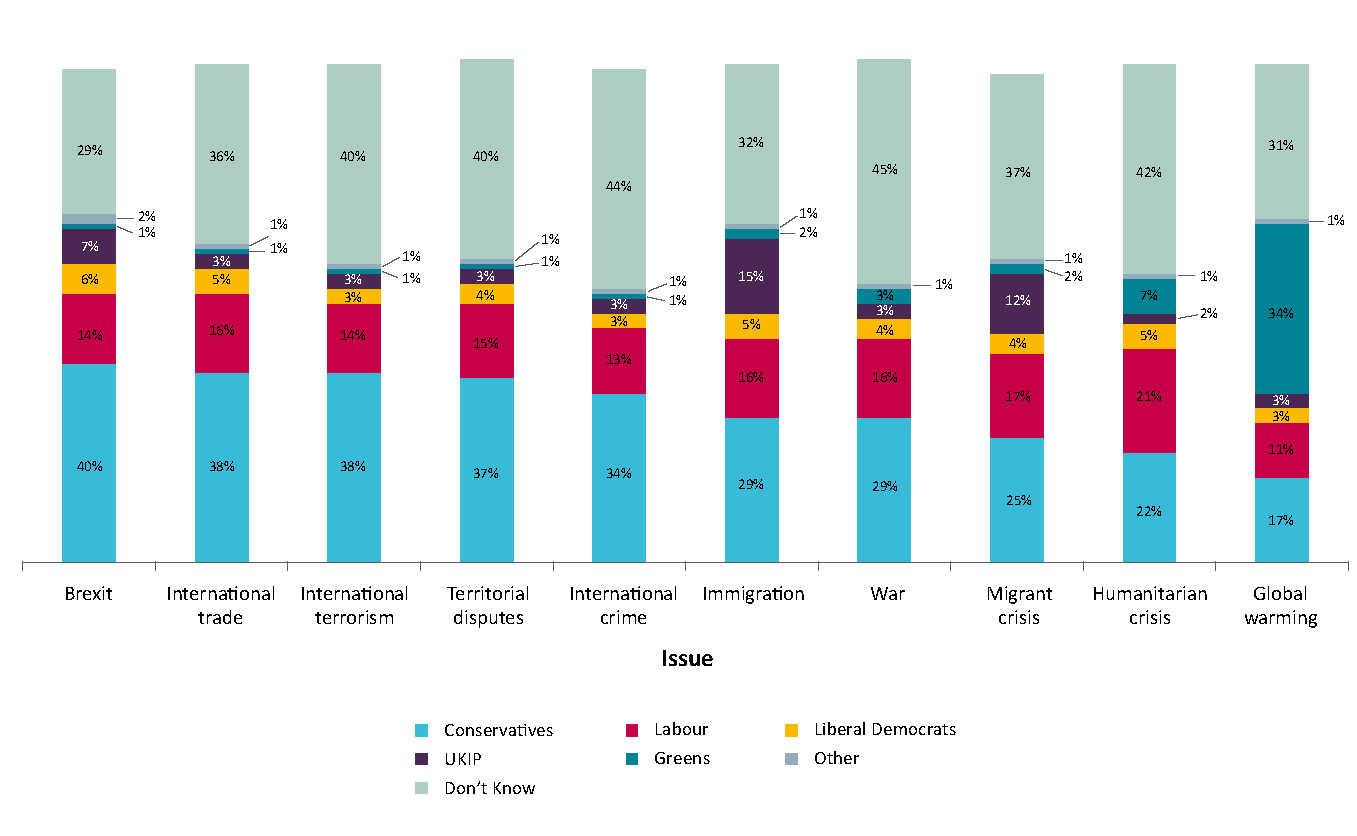

The polling also reveals that voters are aware of the perceived differences in foreign policy stances between the main British political parties. Figure 2 shows what political parties the public thought best addressed a range of foreign policy issues.

While it is interesting that the Conservative party was viewed as the most able to address all of the foreign policy issues asked about, apart from climate change, more revealing is the percentage of 2015 Labour, Liberal Democrat, UKIP and SNP voters who thought in the run-up to this year’s election that the Conservatives best addressed these issues. Of the people surveyed, 24.9% voted Conservative in the 2015 general election. Therefore, on seven of the ten issues polled, the belief that the Conservatives are the best at dealing with these issues extended beyond their voter base.

This apparent support for the Conservative party’s ability to address major foreign policy issues does not imply that the Conservatives gained votes due to their foreign policy; however, it does suggest that this is an area where it might be possible to influence voting intention.

The general election has revealed some of the current divisions in the UK, some new and some old. These divisions are clearly replicated in the public’s foreign policy opinions, along the lines of age, level of education, gender and – to a lesser extent – region.

Alongside age, one of the strongest differentiators is level of education

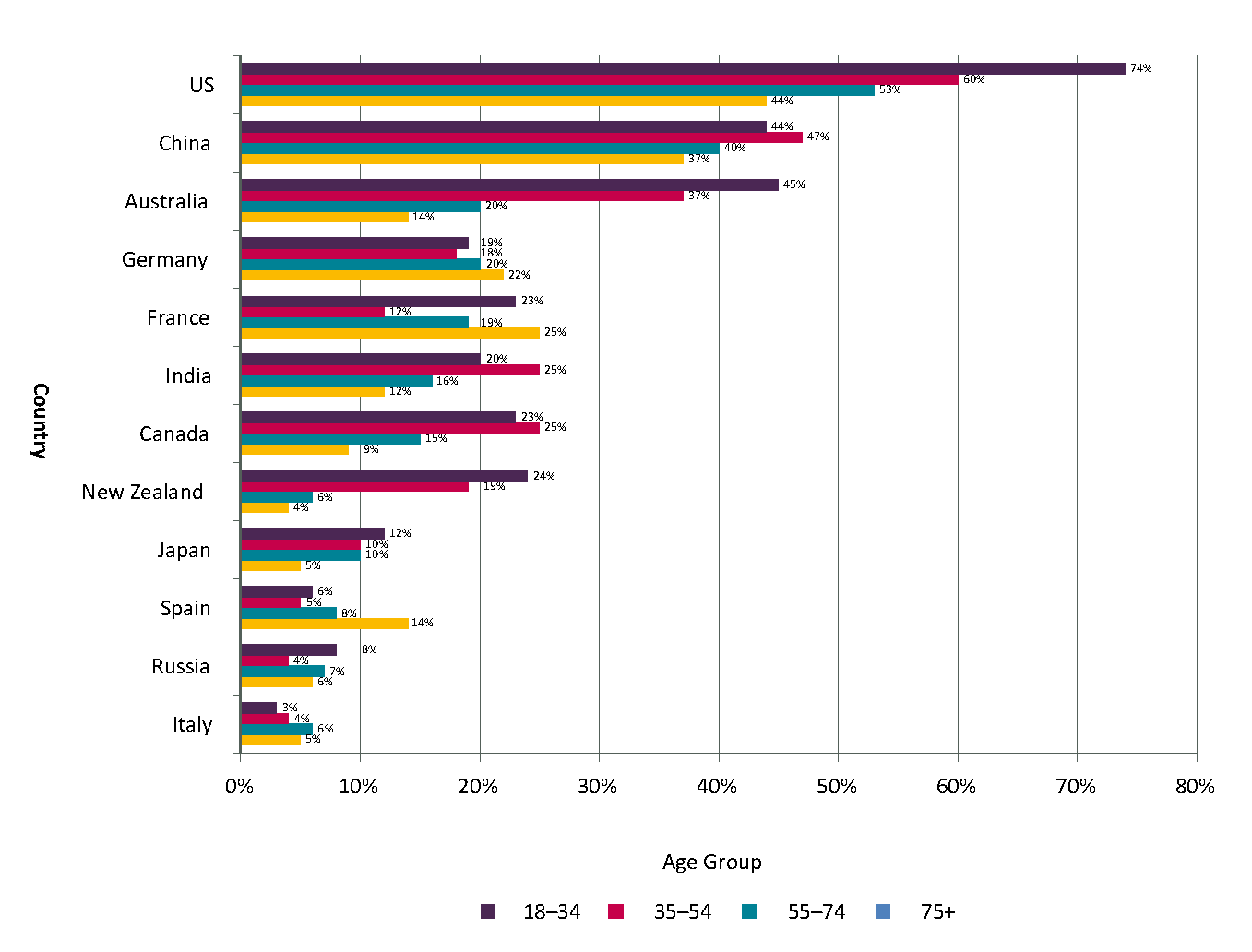

Age is one of the most striking differentiators. Across almost all categories, the pattern is that the greater the age difference, the greater the difference in interest and opinion. Over-75s are more likely to be interested in foreign policy than 18–34s (by 30%), and more likely to feel informed (by 26%). Almost three quarters of those aged 75 or older said that the UK should focus on increasing its trade links with the US, compared with less than half of those aged 18–34 (see Figure 3 on the next page). Likewise, 24% of those aged 75 or older though that the UK should increase its trade links with New Zealand, compared to only 4% of those aged 18–34.

Alongside age, one of the strongest differentiators is level of education. Those with a university degree are more likely to be interested in UK foreign policy (by 31%) than those with no qualifications; they are also more likely to feel informed (by 35%).

The referendum vote on the EU has created a new category of division of opinion within the UK. Remain voters are only slightly more interested (by 8%) in UK foreign policy than Leave voters, and are slightly more likely to feel informed (by 6%), but there is a greater difference when it comes to UK foreign policy priorities. Unsurprisingly, Remain voters are more likely to support the UK’s membership of international organisations than Leave voters, as well as institutions such as the IMF (by 24%) and the World Bank (by 17%). Some 40% of Leavers said that the UK should increase its trading links with Australia, almost double the percentage among Remainers (21%). Those who supported Brexit in 2015 were less likely to say that the UK should increase its trade links with either France or Germany (12% and 13% respectively) than Remainers (21% and 26% respectively).

It is however important to bear in mind that the division between Leave and Remain voters includes many divisions in itself – notably the two major ones of age and education.

There is also a variance across the regions. Some of the biggest differences can be seen between the Northwest and the East of England, (66% of the respondents in the Northwest said that they were interested in UK foreign policy, compared to 51% in the East of England), and between London and the East, Northeast, Southwest and Wales (44% of respondents felt informed about UK foreign affairs in London, compared to less than 35% of respondents in those other regions).

Men also tend to be slightly more interested in foreign policy issues than women (by 6%) and feel themselves – and actually are – more informed as well (by 9% and 17% respectively).

What these results also show is the lower importance of the rural/urban divide with regards to foreign policy – while there are some regional differences that are highlighted by the polls, they are small in comparison to other categories, such as age and education.

Amidst social change, and the increasing complexities surrounding our foreign policy, we cannot afford to continue to take for granted the public’s support for established foreign policy positions.

Foreign interference in domestic policy discussion in order to achieve particular outcomes is not new, but it does seem to be on the rise again and taking on new forms. For the UK, as for other countries, a greater level of public engagement and understanding of foreign policy issues may offer the most reliable path to resilience in the face of external attempts to manipulate opinion. This should be prioritised to ensure the UK continues to be an influential and constructive global actor that protects and enhances our security, prosperity and influence for the benefit of Britain and the world.

Edward Elliott

Research and Operations Manager at the British Foreign Policy Group.