A century ago today, the Treaty of Trianon carved up the territory of Hungary, consigning the rump country to the status of the single biggest loser of the First World War. Trianon’s consequences, for both Hungary and its neighbours, continue to reverberate.

This year happens to be particularly rich in anniversaries for Hungary. It is 30 years since the election of the democratic government in 1990, the last symbolic act of the end of communism, though not of the nomenklatura which had successfully salvaged much of its power, above all in its control of the media. It is also 10 years since the Fidesz government won power with a majority that permitted it to implement constitutional changes to endless leftwing (local and Western) gnashing of teeth. But above all there is Trianon, the 100th anniversary of the treaty that ended the First World War for Hungary, one of several treaties of the Paris Peace Settlement.

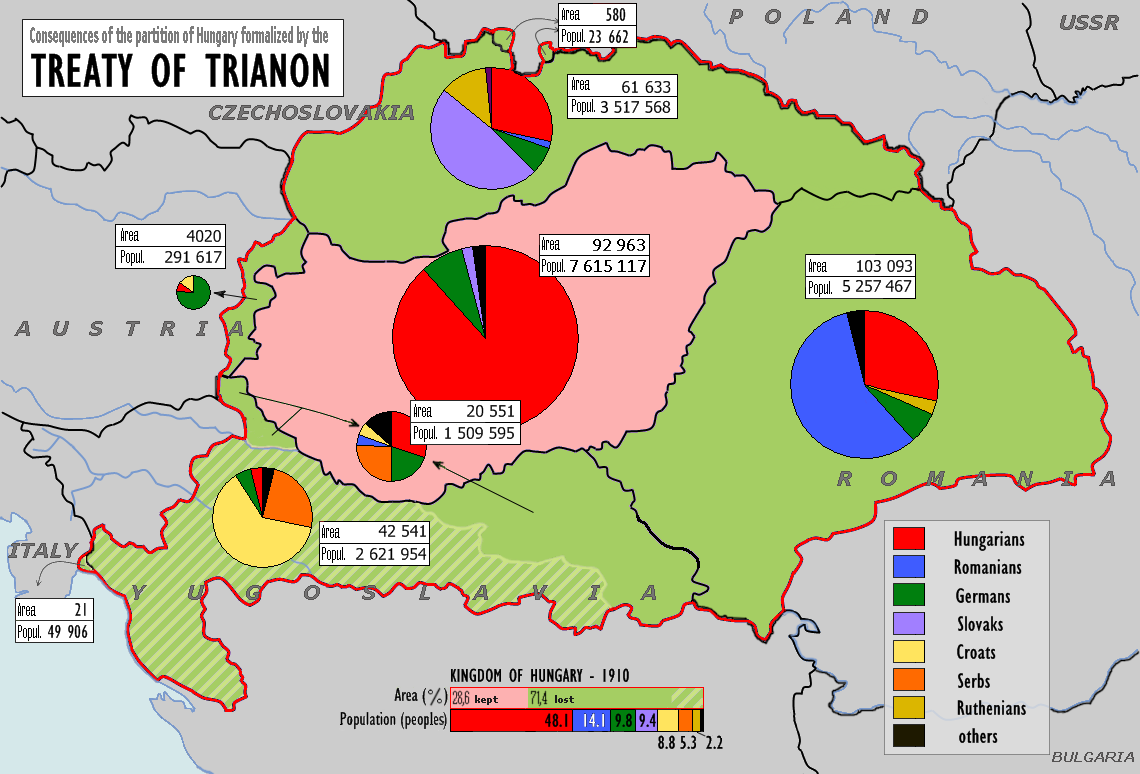

This was and is a caesura, a traumatic event, in which Hungary was helpless, without agency, and barely escaped being carved up entirely among its ill-disposed neighbours. They liked the idea of a ‘Slav corridor’ through western Hungary linking Czechoslovakia and the South Slav Kingdom; Romania wanted the River Tisza as its western frontier; and Czechoslovakia sought to extend its territory well to the south of the present line. The Entente Powers would not go quite that far. But it added up to a variant of state failure all the same. Hungary pulled itself together somehow, but trauma of losing so much territory and around three and half million ethnic Hungarians has cast a very long shadow. After all, no state likes to lose territory – just look at France and Alsace-Lorraine. Quite apart from anything else, the three million were wholly deprived of the choice to be citizens of the successor states. Most of them did not, so it was a trauma for them too.

In Denial – Never to Trianon

How does one exit trauma? Basically, you try to create a narrative of explanation as to why you failed. For Hungary this was straightforward enough: blame France and its client states of the Little Entente, the insecurity system comprising Czechoslovakia, Romania and Yugoslavia that eventually exploded in 1938–41. Territories were then recovered by Hungary before and during the Second World War, but these were lost again afterwards, meaning that frontier revision was definitively abandoned, even if the beneficiaries of Trianon still have more than the occasional frisson about Hungary’s objectives. This is significant. Trianon is not just a Hungarian affair, but is present in the successor states too, sometimes on-stage, mostly off-stage.

Some 12 years or so ago, the Slovak National Party published a map of Central Europe from which Hungary had been made to disappear. (Hypothetical map of Southeastern Europe without Hungary originally published on the website of the Slovak National Party. Now available at https://central.blogactiv.eu/2008/04/17/drawing-maps/)

Still, this was EU time, so no one batted an eyelid. The former president of Romania, Traian Bǎsescu, even noted that Romania’s western frontier was, and should be, the River Tisza. Given that Trianon can be regarded as the mythic founding narrative of both Romania and Slovakia, one can see its rationale, seeing that the Hungarian narrative self-evidently questions this and, implicitly, the legitimacy of the dismemberment.

Note that these statements caused not a stir in the West. Had a Hungarian politician made similar comments on extending that country’s frontiers, the reaction would not have been as muted. There have also been troubles with Ukraine over the cut-backs to the right to education in the mother tongue. This dispute is unsettled. Still, all is quiet on the southern front; relations with Yugoslavia’s successor states are untroubled, very good with Serbia and Slovenia, and correct with Croatia.

Communism and Thereafter

During the communist period, Trianon was strictly off the agenda and the ethnic Hungarians living beyond Hungary proper were quietly ignored; after all, comradely internationalism ruled. The 1956 Hungarian Revolution was not well received by the successor states, especially as the trans-frontier Hungarians clearly identified with Budapest. But the Soviet invasion put an end to that. Still, as a little footnote, apparently Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev offered to return Transcarpathia, annexed to Ukraine, in 1961, but the Hungarian communists, fearful of change, said no.

So, Trianon was a frozen issue. But the collapse of communism unfroze it. The newly elected prime minister, József Antall, announced that he saw himself as the prime minister of 15 million Hungarians ‘in spirit’, as it was widely (mis)translated; what he actually said was ‘in my soul and feelings’. In the fluidity of the time, this statement did not go down well in the successor states, but it did bring Trianon as the symbol of the trans-frontier Hungarians back to the Hungarian agenda. The Hungarian Left, however, wanted nothing of it. For them, the approximately 3 million trans-frontier ethnic Hungarian communities were a dead issue. But they no longer controlled the narrative.

Fidesz, a small youth-radical party in 1990 may have styled itself liberal at the time, but it always had a sense of Hungarian nationhood as a living reality. The Fidesz project included the open acknowledgement of Hungary and all Hungarians as one cultural nation, with shifting political content, basically demanding equal rights – there are plenty of European declarations in support of minority rights to refer to – but an absolute ‘no’ to frontier revision.

Viktor Orbán’s annual speech in Bǎile Tuşnad/Tusnádfürdő, in central Transylvania in Romania, communicates this multiple message. This author did once suggest the launching of Hungarophony, using the Francophonie – the association of French-speaking states – as the model, but it never got anywhere.

When Fidesz formed its first government (1998–2002), Trianon was there as a negative symbol, a failure to be overcome, which is why the so-called ‘Hungarian certificate’ – a document providing ethnic Hungarians in neighbouring states and their dependents rights in Hungary itself – was launched with the aim of giving certain rights to the trans-frontier minorities in Hungary as kin state. This went down badly in Slovakia, Romania and in the West. The new Hungarian leftwing government elected in 2002 scrapped it.

So, it was only after the 2010 Fidesz victory that Trianon was upgraded and became a focal point of Hungarian identity. In many ways, this is a somewhat puzzling aspect of Hungarian identity construction. Chronologically, Hungarians remember the defeat by the Ottomans in 1526, the Rákóczy insurrection of 1703–11, the 1848 revolution against Austria, the 1918 Aster revolution and the 1919 Soviet Republic, the double invasion (German and Soviet) of 1944–45 and, of course, 1956. What is striking about all of these is that they ended in failure, some cataclysmically so. Hungary ended up on the losing side of every war it was involved in for 600 years, until the 1990–91 Gulf War (a symbolic participation, it should be added). Not what one might call a glorious record.

The Trianon Wound Today

The post-2010 Fidesz project was to change this. Trianon was no longer the symbol of grief and grievances, but the Day of National Belonging (Law 2010 XLV) – all Hungarians can commemorate their identity on the day of collective belonging. Mindful of the failure of the ‘certificate’ project, Fidesz concluded that the next step would involve one key part of state sovereignty. It was decided to offer Hungarian citizenship to all who had Hungarian antecedents with a relatively lightweight language exam. Over the years, about a million took advantage of the provision and that number included those non-Hungarians whose forebears had been citizens during the war (for example, Vojvodina Serbs). There was nothing much that the successor states could do, seeing that they too offered dual citizenship to ethnic kin. Slovakia did, however, ban dual citizenship.

Every collectivity – including states and nations – constructs a memory regime, providing a focus on a particular aspect of the past. There is nothing inherently reprehensible about this; it is the way in which collectivities maintain themselves. The friction arises when these memory regimes clash, when divergent narratives become foundational, as they have with Trianon. Little did they know – the delegates in Paris – that 100 years on, their activities would still be a cause for dispute.

2020 is, as we have seen, the centenary of Trianon, but given the coronavirus, there is to be no public event on 4 June. But the new Trianon monument, opposite parliament, will be unveiled before long. It consists of stone walls with the Hungarian place names of every settlement in pre-1918 Hungary.

In response, as it were, Romania has declared 4 June a national holiday. The long shadow of Trianon remains.

Figure 2: The Consequences of the Treaty of Trianon

György Schöpflin served as member of the European Parliament for Hungary between 2004 to 2019, and is currently senior research fellow at the Institute of Advanced Studies Kőszeg.

The views expressed in this Commentary are the author's, and do not represent those of RUSI or any other institution.

BANNER IMAGE: Ceremony at the signing of the Treaty of Trianon, 4 June 1920. Courtesy of Gallica Digital Library