A wave of protests sweeping the country may, unlike previous crises, be quite significant.

An old joke has it that political life in Sudan ‘changes from week to week, but if you come back after ten years it is exactly the same’. Unfortunately, international commentators largely ignore this adage, and end up offering analysis that ascribes a disproportionate significance to short-term fluctuations in Khartoum while overlooking broader structural trends. As a result, any hints of discontent usually elicit predictions of regime collapse when they are often nothing more than routine junctures in the turbulent milieu of Sudanese politics. Still, the unrest that flared up in the country in December 2018 could be more than a flutter, and thus amount to something very different.

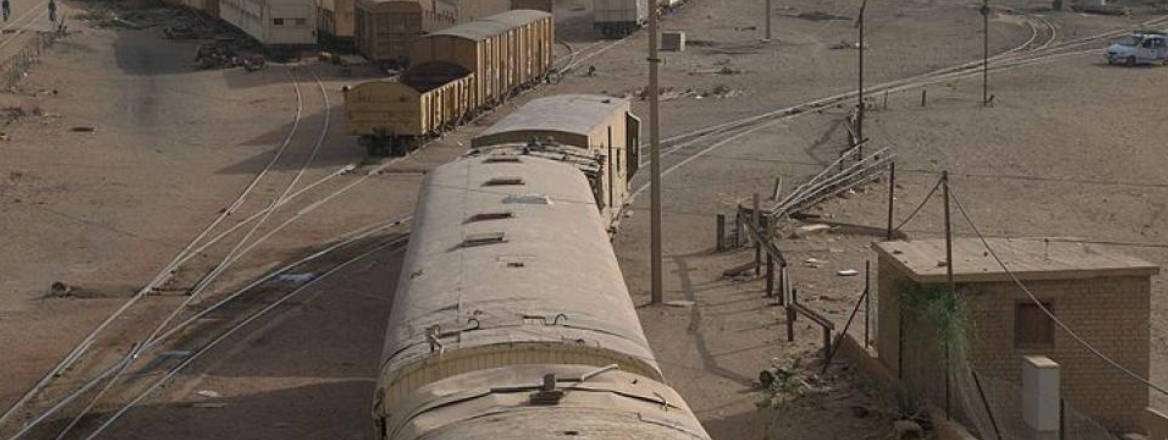

Economic malaise appears to be the immediate grievance driving these demonstrations, which started in Atbara, a provincial hub 350 km from Khartoum, before spreading to over 28 towns and cities. Protestors’ concerns are easy to identify: national insolvency, debt and a lack of hard currency are distorting local markets, contributing to spiralling inflation and shortages in staple commodities from wheat to pharmaceutical goods to fuel. Bakeries are empty, subsidies have been drastically cut and volatile prices are disrupting supply chains and service delivery. None of this is particularly new in a country isolated by international sanctions.

But in contrast to previous economic crises, the deprivation is not only impacting Sudan’s impoverished masses but is now reaching more the occupants of upscale neighbourhoods. White-collar professionals and civil servants are no longer able to withdraw salaries from Khartoum’s banks, straining a tacit bargain struck between President Omar Al-Bashir, who has ruled the country for three decades and Sudan’s metropolitan bourgeois, who were offered stability and comfort provided they stayed quiet. A break in this arrangement could prove crucial, for the Bashir regime’s kleptocratic disposition relies on the buy-in of national elites. As long as these stakeholders were able to collude and prosper, the frustrations of those on the lower rungs of society could be ignored.

Under these provisions, a political–business model has gradually matured, allowing the government to exploit Sudan’s economy, public services, military and industries to maintain its monopoly over the means of extraction. Everything that could not be monetised withered, particularly in outlying peripheries like Darfur where local institutions were starved of funds. These arrangements were tolerable while they benefited the country’s riverine core, enabling Bashir’s National Congress Party (NCP) to purchase local support by delivering semi-public goods, financial patronage and a lucrative stake in the status quo. But it appears the government ‘has lost control over the basics’ by failing to maintain the living standards of its erstwhile friends. As a result, the regime is now facing a broad cross-section of Sudanese society clamouring for change, even in traditionally staunch NCP strongholds.

Sudan has experienced revolutionary change before: uprisings in 1964 and 1985 overthrew incumbent military dictatorships when ‘middle class folks’ turned isolated riots into a broad movement for political change. The analogous dynamics characterising the current protests may therefore explain why Bashir is so perturbed, particularly as the conventional modalities of Sudanese authoritarianism – cash-based ‘carrots’ and a big stick – don’t seem to be working. Promises to re-introduce wheat subsidies and swell government spending by 39% have fallen on deaf ears, and the messaging circulated by state broadcasters – blaming agitation on Darfuri rebels, vandals and looters – is widely ignored. Over 800 people have been ‘officially’ detained and 40 killed by police, National Intelligence and Security Service (NISS) agents and hired militias, with members of the Sudanese Professional Association, a coalition of highbrow trade unions, being singled out. Nevertheless, the demonstrations show little sign of abating. If anything, they are becoming more organised. What was originally a surge of spontaneous emotion has assumed a strategic edge and morphed from calls for economic relief to demands for regime change.

Despite his proven capacity for endurance, Bashir also has far less space to manoeuvre than he has done previously, due in part to his own administrative mismanagement. The 2011 secession of South Sudan, along with 75% of Khartoum’s oil reserves, undoubtedly exacerbated his difficulties by diminishing the flow of Sudan’s primary export and source of foreign exchange.

But a lack of economic diversification and long-running neglect of other commercial industries including agriculture and manufacturing are the outcome of frenetic policymaking, over-taxation, harassment and pervasive graft. This leaves Bashir with few options. Dividends from the partial lifting of US sanctions in 2017 have been disappointing, and yields from a burgeoning gold market remain meagre given that most artisanal mines – responsible for 90% of national production – operate outside the government’s control.

The financial largesse of Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, a historical lifeline for the regime, has also become unpredictable. Neither seems inclined to offer bailouts and further investment is contingent on expensive levies, including Sudan’s unpopular contribution to the intervention in Yemen. In short, Bashir is grappling with the same paradox of many strongmen: lacking the capital to assuage domestic opposition or buy new friends, he faces the prospect of having to grant real political concessions he may not necessarily survive.

However, this is by no means guaranteed, for Bashir’s regime has a tradition of being nimble. By appropriating the rubric and residual trappings of Sheikh Hassan Al-Turabi’s Islamist experiment in the 1990s, the regime forestalled any viable religious insurrection akin to those that gradually co-opted the Arab Spring uprisings in 2011. Bashir’s longevity has likewise left secular opposition parties latent, discredited or outdated. As an adept manager of the Sudanese political marketplace, he also appears to have coup-proofed his Presidency, leaving few obvious replacements for the top job.

This derives, at least in part, from the logic of retail politics in Sudan, where patronage acts as a circulatory system for dispensing state rents and procuring loyalty. Bashir has built a cabal that allows different stakeholders – from security tsars to corporate magnates and municipal party bosses – to glut themselves on public revenues in return for their support. The trick is to satiate these beneficiaries without providing space for those in favour to build a durable clientele system of their own. Rotating elites and encouraging rivalries are useful safeguards and Bashir has maintained a flexible approach: reshuffling or dismissing key lieutenants, including ex-NCP Secretary General Nafie Ali Nafie and former Vice President Ali Osman Taha, to secure his authority. Security institutions have similarly been divided and duplicated, creating a range of organisations replete with their own patronage networks to dilute the influence of senior officers. While NISS, the Rapid Support Forces, the Sudanese Armed Forces and a host of local militias all consume a sizeable chunk of Sudan’s bloated defence budget, they nevertheless exercise relatively low bargaining power when they are in competition with each other.

The problem for Bashir is that these considerations are neither fixed nor anchored in any genuine ideological commitment. Instead Sudan’s current political marketplace is almost exclusively defined by a utilitarian logic: as soon as his value diminishes for a sufficient number of clients, they may abandon him. Whether the uprising will achieve critical mass or Bashir can cling on to power in some form is still in the balance. But unless he can restore order, mollify demonstrators and satisfy the appetites of his entourage – contradictory priorities given the nature of the protests – it may be a race to see which finds him disposable first: the country, or the regime.

The views expressed in this Commentary are the author's, and do not necessarily reflect those of RUSI or any other institution.

WRITTEN BY

Michael Jones

Senior Research Fellow

Terrorism and Conflict