Soldiers and Social Media in the Age of Connectivity Saturation

The diffusion of social media platforms can both help and hinder military forces’ operational output, and means it is increasingly difficult to manage and police. Improper use can lead to security implications and even lethal targeting. It can also erode unit cohesion and cause disciplinary issues, distracting units from preparing for and conducting their core output, whether at home or abroad.

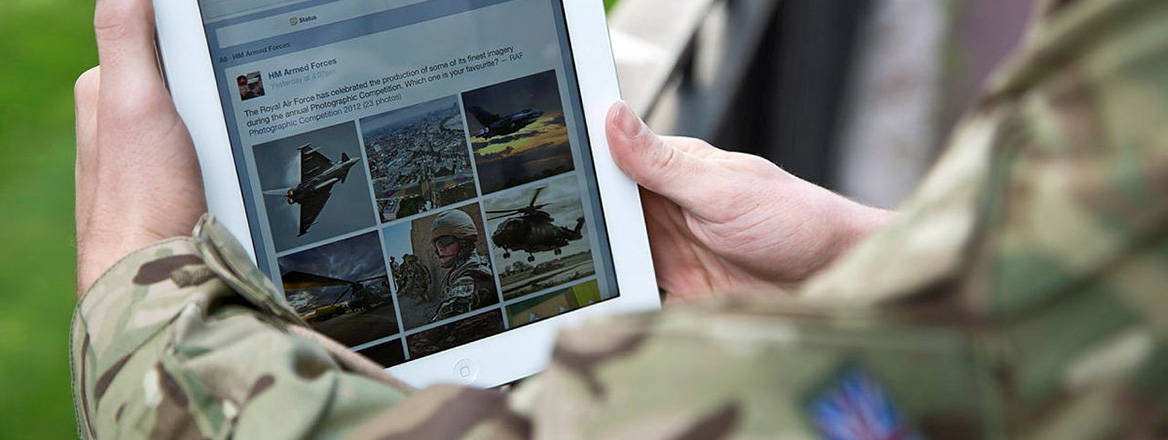

Missile strikes in Ukraine, assassinations in Russia, leaks of state secrets in the US, arrests and jailings in the UK: all these events are linked to the use of social media by military personnel. Instagram, Twitter (or X), Threads, Facebook, Snapchat, TikTok, Twitch, Discord, LinkedIn, Strava, Reddit – the list of social media platforms goes on, and continues to proliferate. For most people, the use of social media is innocuous. For military personnel, however, there are numerous risks involved with using these platforms, from giving away sensitive information to criminal activity. Keeping track of soldiers’ online activity is difficult – they might have multiple social media accounts and may use their own name, pseudonyms or tags. People can broadcast content to an audience in an instant with no cost, and potentially little thought.

It has long been recognised that putting military business online is a bad idea. However, today there are a multitude of ways for soldiers to interact with social media, and the arena is only becoming muddier. Total prevention of online activity is impossible. There are two lenses through which to look at the issues surrounding military personnel’s use of social media. The first is security, and the second is reputational repercussions. This article will not tackle the subject of radicalisation of military personnel on social media, which has been covered in detail elsewhere.

Security Concerns

The principal fear where soldiers are posting information on social media is a breach of operational security. Giving away locations and force dispositions to an adversary is a real threat which can lead to casualties. Early in the Ukraine conflict, it became clear that social media was providing information that was then used for targeting. In August 2022, a Ukrainian missile strike hit the city of Popasna, hitting a building used as a headquarters for soldiers from the Wagner Group. The building was destroyed, and an unconfirmed number of casualties occurred. The location had been identified due to the social media activity of the soldiers, who posted photographs on the Telegram messaging and broadcasting application.

This is not the first time such fears have been realised, and forces have taken precautions against being located through social media activity – although their effectiveness is questionable. In 2018, it was widely reported that soldiers from Western forces in Afghanistan and Syria had inadvertently revealed the locations of military bases in the region after uploading their exercise data to the Strava fitness application. More recently, it was suggested that the assassination of a former Russian submarine commander during a morning run was made possible by the fact that he uploaded his regular route to Strava.

There is a delicate balance to be maintained as young soldiers’ lives are tightly intertwined with access to their phones and the wider internet

In 2019, researchers from NATO’s Strategic Communications Centre of Excellence ran an experiment during a major military exercise. Using social media, the research team was able to identify exercise participants and encourage them to join fake Facebook groups which looked like they were officially linked to the exercise. By analysing these profiles, they were able to identify other soldiers, precise locations of troops and contact details, and see photographs of equipment. Most worryingly, some soldiers were persuaded to leave their positions and to fail to carry out their duties.

Most military forces have a policy about the use of mobile phones, the most common route to accessing social media when deployed. For instance, the Russian parliament voted to ban military personnel from deploying with mobile phones back in 2019, but it is clear from the invasion in 2022 that this was by no means an effective measure. There might be a middle ground where soldiers must use a Virtual Private Network (VPN) on their phones to mask their locations. Indeed, many Western states run exercises where phones are banned, or must be handed in to commanders. Yet it is not unknown for enterprising soldiers to take a spare and keep it in the bottom of their sleeping bag so they can maintain access to the outside world.

There is a delicate balance to be maintained as young soldiers’ lives are tightly intertwined with access to their phones and the wider internet. Cutting them off entirely can have a detrimental effect on morale. The Royal Navy is struggling to recruit submariners, critical to the UK’s continuous at-sea nuclear deterrent, due to their desire to be able to access social media. UK submariners can receive two 60-word messages a week which cannot be replied to – a far cry from the constant connectivity which has become normal for most young people.

Education and raising awareness are likely the best way forward to mitigate these vulnerabilities. In the UK, the security environment appears more permissive than it has been in previous decades, and young soldiers may not be fully cognisant of the precautions that have been taken in the past to prevent them from being identified as members of the military. Posting photos of bases and activities can help malign actors identify potential targets. The Troubles and the threat of attacks from the IRA meant generations of soldiers were used to checking under their cars and being vigilant, and many had personally lost friends and colleagues to terrorist activity. This memory has faded with time. Indeed, it has been over a decade since the murder of Lee Rigby. While both physical and online personal security training is conducted annually, it can feel abstract if the real world seems safe.

A polarised political environment has seen soldiers take to social media to air political views, which goes against most forces’ codes of conduct

More nuanced activity can include service personnel putting their level of security clearance on professional sites such as LinkedIn, thereby demonstrating access to sensitive information. Despite LinkedIn being ostensibly more ‘serious’ than many other sites, this makes it even more dangerous. It is recognised that the threat of state-based adversarial activity on social media is growing. Between 2016 and 2021, it is believed that over 10,000 disguised approaches were made by foreign agents looking to build relationships with military and civilian individuals with access to sensitive information. A renewed wariness of malign activity by state actors can be recognised after decades of focus on non-state actors.

Disciplinary Issues

Aside from the acute security concerns discussed above, social media use can also affect internal discipline, the ramifications of which may later play out on the battlefield. The actions of soldiers are judged by their impact on operational effectiveness – that is, the degree to which a force can complete its objectives. The Queen’s (yet to be updated to account for the accession of King Charles III) Regulations for the Armed Forces are the UK military’s rules for conduct and discipline. The Service Test is used to determine whether an action might be considered as misconduct and therefore potentially at risk of facing an investigation and sanction. The test asks, ‘have the actions or behaviour of an individual adversely impacted or are they likely to impact on the efficiency or operational effectiveness of the Army?’ Much activity on social media can fall foul of this definition. Social misbehaviour can undermine operational effectiveness by damaging trust and cohesion. Bullying or trolling fellow servicepeople on social media can be included in this bracket. A polarised political environment has also seen soldiers take to social media to air political views, which goes against most forces’ codes of conduct. Servicepeople are generally allowed to be part of a political party, but must refrain from publicly airing political views. Both senior and junior soldiers have fallen foul of this rule and faced disciplinary action. Another nuance that is specific to military activity and can lead to bad outcomes is social media use in the event of a casualty at home or overseas. Operation MINIMISE is the name given to the order for all personnel to minimise communication with the outside world while the official process to inform the casualty’s next of kin is carried out. If soldiers inadvertently send information about a casualty and news reaches the family informally, or via the news media, this will have a negative effect on the force’s standing. The outcome might be even more damaging if the information being shared is incorrect or incomplete.

Social media also offers soldiers the opportunity to make additional money. It is widely recognised that public sector pay is bested by the private sector, and military forces find it difficult to compete, even with wide-ranging benefits packages that include accommodation and medical support. Traditionally, secondary employment has included driving lorries at weekends, or perhaps working as a bouncer at a nightclub. Now, soldiers can make money from streaming activities on Twitch or selling images and videos on content-sharing platforms like Only Fans. This is not unacceptable in itself, but must align with existing rules such as not representing the individuals involved in the activity as members of the armed forces and not bringing the services into disrepute. Activity on social media can range from the totally innocuous through to illegality, such as uploading intimate images and videos without consent.

The problem of social media use by military personnel is complex, with many interlocking strands. Personal and operational security can be harmed by improper or careless use, showing the continued relevance of the Second World War’s ‘loose lips sink ships’ idiom. Balance is everything. Social media is used by senior officers as a strategic communications tool to advance national objectives, whether by reassuring allies or deterring adversaries. It is also used by units and formations to attract people to enlist in a challenging recruiting environment. However, there is ongoing evidence of poor, improper and illegal behaviour which can impact team cohesion and play into the hands of adversaries.

The views expressed in this Commentary are the author’s, and do not represent those of RUSI or any other institution.

Have an idea for a Commentary you’d like to write for us? Send a short pitch to commentaries@rusi.org and we’ll get back to you if it fits into our research interests. Full guidelines for contributors can be found here.

WRITTEN BY

Major Patrick Hinton

Former Chief of the General Staff’s Visiting Fellow

Military Sciences

- Jim McLeanMedia Relations Manager+44 (0)7917 373 069JimMc@rusi.org