The New UK Counterterrorism Strategy: Critical Questions for the ‘Prevent’ Strand

A new version of the UK’s counterterrorism strategy (also known as CONTEST), was unveiled earlier this month. Of the four strands comprising CONTEST, it is the Prevent strand, preventing individuals from becoming terrorists and supporting terrorism, that elicits the strongest reaction from different sections of British society.

The publication of a new Prevent strategy within the CONTEST framework (consisting of Prevent, Pursue, Protect and Prepare) is important for several reasons. First, we have a new home secretary who will be eager to leave his mark on the new approach. And, following a seven-year hiatus since the last strategy, Prevent must be updated to reflect the changing security threat, moulded by: the Syrian conflict; growth in the role of social media in recruiting to terrorism; the emergence of Daesh (also known as the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria, ISIS) in 2014; the proliferation of ‘low-tech’ attacks; the challenges posed by returnee foreign terrorist fighters, including women and children, from the Middle East; the growth of far-right terrorism; and the release of prisoners sentenced under the Terrorism Act 2000 and its successors (known as TACT offenders) and their reintegration into society.

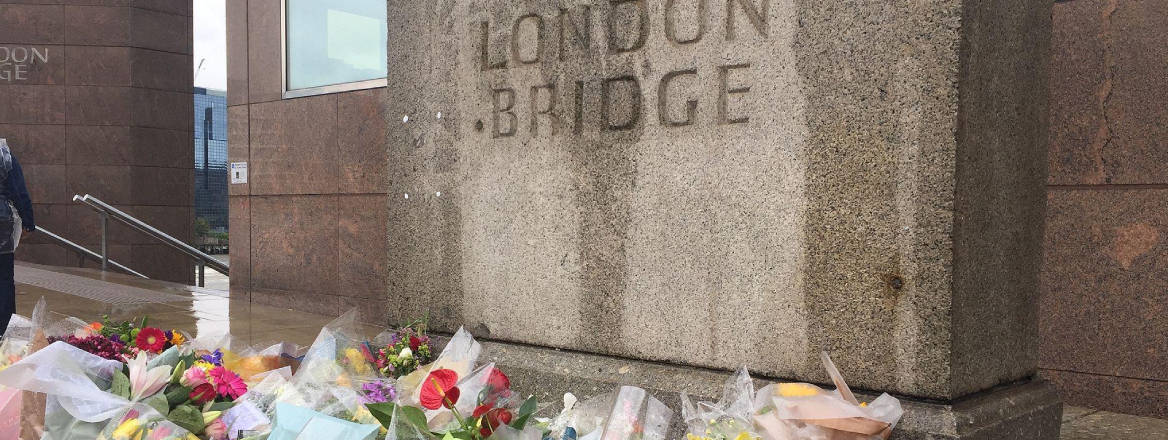

Furthermore, there has also been an unprecedented level of scrutiny of the security services��’ handling of individuals previously known to be ‘subjects of interest’ and who later went on to commit acts of terror. The question has been asked following the Westminster, Manchester and London Bridge attacks last year whether more could have been done in the preventive space to monitor former subjects of interest.

Finally, given that there is a duty on specified authorities to have due regard of the need to prevent people from being drawn into terrorism – also known as the ‘Prevent duty’ – many sections of British society (including teachers, lecturers, probation officers, students, health professionals, as well as members of civil society and British Muslim communities) will be scrutinising the evolution and development of the strategy, not only out of interest, but for employees of the state, also out of professional responsibility.

The new element to the Prevent strategy is the inclusion of ‘Desistance and Disengagement Programmes’ (DDP) under its purview. These programmes are aimed at individuals already engaged in terrorism who are required to disengage and reintegrate back into society. The introduction and proposed expansion of DDP targets a wider category of people, including individuals subject to court-approved conditions: terrorism and terrorism-related offenders; those on Terrorism Prevention and Investigation Measures (TPIMS); and those who have returned from conflict zones in Syria or Iraq and are subject to Temporary Exclusion Orders (TEOs). In contrast to the existing Channel Programme, which focuses on providing support at an early stage to people who are identified as being vulnerable to being drawn into terrorism, but requires the consent of those individuals, the participation of TACT offenders in DDP is mandatory.

The concept of desistance denotes the process by which individuals cease criminal activity or offending, whereas disengagement describes the process of ceasing terrorist activity. In contrast to de-radicalisation, which aims at changing the ideas and beliefs of TACT offenders in view to changing their behaviours, desistance and disengagement programmes aim at changing the behaviour of offenders, namely the cessation of terrorism. DDP is premised on the notion that changing the ideas and beliefs of offenders is ineffective on its own in stopping individual engagement in terrorism, without being accompanied by other provisions (social support, material incentives and other inducements), as well as being unworkable as an interventional goal. After all, it is extremely difficult to accurately measure and test changes in belief scientifically, whereas changes in behaviour – a changed role for individuals within a terrorist group, an individual disconnecting from other terrorists or simply walking away from terrorism – is empirical and easier to gauge as an intervention objective.

These additions made to the Prevent pillar pave the way for the adoption of Pursue objectives for the first time. This is significant operationally because Pursue, in principle, focuses on those who have crossed the threshold into terrorism, whereas Prevent’s modus operandi, in contrast, concerns the long-term prevention of latent threats of terrorism from emerging in the first place in civilian life. Although it is too early to judge what the implications of DDP in Prevent will be, the current absence of evidence in the wider literature that disengagement and reintegration interventions actually work suggests that success in DDP may be slow and gradual at best and, at worst, inconsequential.

Despite the conceptual, strategic and operational differences between Prevent and Pursue, this move towards working across the four ‘P’ strands are framed as natural and necessary considering the shift in threats facing the UK. This may also reflect the government’s decision to streamline some of CONTEST’s activities under the logic of efficiency savings. After all, there is no clear commitment in the new strategy to increasing investment in Prevent capabilities. Perhaps it also reflects the more pragmatic decision to maintain the symmetry and elegance of the four ‘P’s instead of creating an additional and separate strand within CONTEST.

Except for DDP, therefore, the Prevent delivery model remains unchanged from its 2011 iteration. Prevent is still organised around ‘three I’s’: Ideas, Individuals and Institutions. ‘Ideas’ refers to the objective of countering Islamist ideology; ‘Individuals’ denotes that the strategy focuses on supporting vulnerable individuals (and not groups or movements) ‘at risk’ of radicalisation, while ‘Institutions’ refers to the way that state institutions have been tasked with the responsibility of identifying individuals at risk of radicalisation, although this focus on institutions is no longer a stated objective in the new strategy.

Notwithstanding such continuities, Prevent 2018, will continue to stimulate public attention and scrutiny into the foreseeable future because of five critical areas of concern:

-

The Concepts of Radicalisation and Ideology as Causes of Terrorism: radicalisation is a contested concept, while the causes of terrorism are highly contextualised, individualised, predominantly not ideological, but multi-factorial and complex. Why, then, does the first objective of Prevent continue to use the concept of radicalisation and seek to respond to ideology when better forms of knowledge can be operationalised?

-

The Evidence Base for Effectiveness: Prevent encompasses a diversity of activities targeting different populations, which includes strategic communication, counter-narratives, community resilience projects, one-to-one interventions like Channel in the pre-crime space and DDP programmes for actual terrorists. The UK government views Prevent as critical to the UK’s success in reducing the risk of terrorism. It has also inspired other preventive counterterrorism programmes in many countries. But Prevent rests on a weak evidence base regarding what works in reducing the threat of terrorism in the UK. Prevent is certainly not alone in this – other policy areas, such as conflict prevention and peacebuilding are also built on weak empirical foundations. Prevent practitioners may also be committed to doing something about it. However, this question regarding whether Prevent works or not is of crucial importance if other approaches exist and are not being adopted. For example, the current strategy is structured according to a public health model. This approach may have its advantages, but it treats terrorism as a disease to be cured and consequently medicalises very complex issues that are non-medical at root and constitution. An alternative approach could treat terrorism as a criminal, social or political problem to be mitigated (rather than cured, which is an impossibility).

-

Safeguarding: the second objective of Prevent is about safeguarding individuals from radicalisation. The lack of research into how the Prevent duty is being implemented in practice calls into question the evidence base supporting Prevent’s approach of framing the risk of radicalisation spreading among a minority in the population in terms of ‘safeguarding’. For example, given that potential terrorists are now seen as individuals who are vulnerable to ideological indoctrination on the one hand and a potential danger to the public on the other hand, is safeguarding against radicalisation really the same as safeguarding against other vulnerabilities? Are teachers, health professionals and public employees being equipped sufficiently with the appropriate knowledge, discretion and confidence to identify individuals at risk of radicalisation?

-

Local Multi-agency Centres: Prevent proposes to develop Multi-agency Centres (MAC) in local areas in order to share information on subjects of interest (SOI) between local areas and the security services. This a response to terrorism undertaken by individuals previously monitored by MI5. The idea is to delegate the responsibility of monitoring individuals who are categorised as less risky than priority cases to newly established centres in local communities. This is a new proposition and details are unavailable, so it is too early to tell how this well develop. At this stage, it is not clear why this proposal is situated within Prevent. But the prospect of MACs in local areas with new powers will need to be scrutinised. A potential concern is the violation of civil rights. Given that most SOIs do not commit acts of terror, that they would not even know that they were subjects of interest for MI5 to begin with, not to mention that protecting the identity of SOIs may prove difficult, how can this pilot develop while protecting civil rights?

-

Extremism as a Strategic Factor in CONTEST: countering extremism is not a feature of the Prevent strategy but has been framed as a strategic factor of CONTEST. Although counter-extremism and Prevent are distinct policy areas, there is potential for the counter-extremism agenda to creep into Prevent activities (which happened between 2006 and 2011), particularly through community resilience projects, online initiatives and frontline professionals tasked with identifying individuals vulnerable to radicalisation. The first problem stems from the opaque framing of extremism. The new version of CONTEST refers to extremism as the ‘promotion of hatred, the erosion of women’s rights, the spread of intolerance, and the isolation of communities’. These are vastly disparate phenomena and policy areas that have been conflated under the nebulous concept of ‘extremism’. Second, the extremism agenda rests on an outdated theory known as the ‘conveyor belt’, which is rejected by Prevent. This theory posits that certain ideas lead progressively and linearly to violence. The notion that extreme ideas lead to violence is a simple one that resonates with people, despite the lack of evidence linking extremism to terrorism. There is a danger that in actual practice, ideas and views deemed unsavoury yet unconnected to terrorism in both online and offline spaces becomes subject to Prevent interventions.

Mohammed Elshimi is a Research Fellow at RUSI.

The views expressed in this Commentary are the author's, and do not necessarily reflect those of RUSI or any other institution.