Modi in Britain: How Does a Rising India View the UK?

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s visit to the UK this week will be the first visit by an Indian leader in almost a decade – despite David Cameron travelling thrice in the other direction. Is the UK–India relationship as healthy as it was?

This week’s visit by the Indian prime minister is significant in several regards. The last purely bilateral visit by an Indian prime minister was in 2006, by Modi’s predecessor Manmohan Singh, and the last trip of any kind was in 2009, when Singh came for the G20 summit in London. That was Singh’s fourth trip in five years. In the six years since, David Cameron has made three unreciprocated trips to India, despite a Joint Declaration in 2004 that envisaged annual summits. The asymmetry speaks for itself.

Then there is the fact that Modi has visited twenty-seven countries before the UK. Those ahead in the queue included Turkmenistan and Ireland. More importantly, they also included France, whose Rafale fighter jets India chose over the Eurofighter Typhoon, and Germany, which poured billions into Indian clean energy projects. While British officials can reasonably point to the obstacle of the general election in May – foreign leaders typically avoid trips extremely close to elections, to avoid suggestions of interference – it would be fair to say that Europe in general and Britain in particular have been relatively low priorities for Modi in relation to the United States, Asia-Pacific, and India’s South Asian neighbourhood.

Yet it would be wrong to suggest that UK-India relations are in a slump. As is frequently pointed out, Britain has been the largest G20 investor in India for over a decade, investing £1.3 billion last year, while India puts more capital into the UK than into the rest of the EU combined, making it Britain’s third largest source of investment. The UK’s diplomatic presence in India is large, with seven deputy high commissions outside New Delhi. Although this is less impressive when adjusted for India’s population or geographic size, it represents a meaningful expansion. And despite Indian grumbling about British immigration policies, the UK gives a third of its work visas to Indians and the vast majority of Indian students who apply for a visa get one, despite the fact that Indian student numbers to the UK halved from 2010/11 to 2013/14.

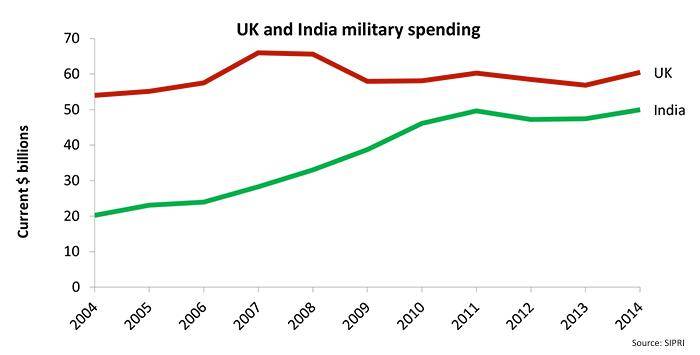

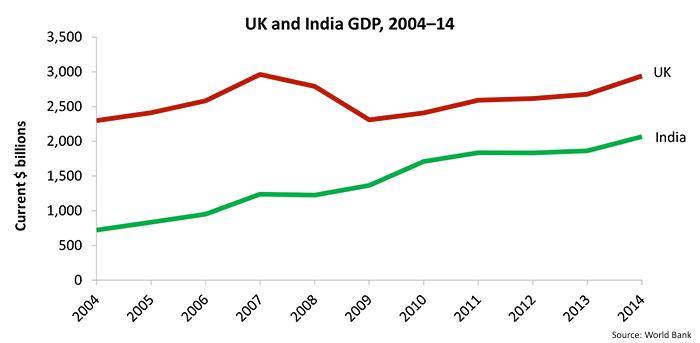

Why, then, is there a sense of stagnation? Part of the answer is that the past decade has been good to India, but forgettable for Britain. Between 2003 and 2010 alone, India underwent the most dramatic and sustained expansion in its modern history, just as the financial crisis hit Western economies. A decade ago, the UK’s economy was three times the size of India’s. Today it is barely 50 percent bigger.

At present growth rates – around 7 per cent for India and 2.5 per cent for the UK – India will eclipse the UK within another decade in absolute terms. It will eventually operate three aircraft carriers to the UK’s two, and continues to develop ever-larger nuclear missiles while Britain is caught in a serious political debate over the future of its own deterrent.

More broadly, the UK and India also find themselves divided on global issues like Syria, Russia and Afghanistan. Above all, Indian diplomats see the UK as hopelessly naïve on the issue of Pakistan. They blame the 1.17 million-strong British Pakistani diaspora, as well as significant defence and intelligence ties between London and Islamabad, for what they see as the UK’s wilful blindness to the Pakistani military’s longstanding sponsorship of terrorism in South Asia. Afghanistan is a particular sore point: when Afghanistan and Pakistan signed a controversial (and now defunct) intelligence pact this summer, despite Pakistani intelligence’s extensive support for the Taliban, the Indian press directed its ire at the UK. Although Indians also censure the US for its own indulgence of Pakistan – especially the past month’s suggestion of a nuclear deal and the planned sale of fighter jets – the UK is seen as particularly suspect, and no doubt an easier target for criticism. It is no surprise that Cameron’s most popular moment in India came five years ago, when – on Indian soil – he called out Pakistani behaviour. If the prime minister is willing to speak as bluntly today – for instance, on Pakistan’s failure to prosecute those associated with the 2008 Mumbai attacks – this could reap significant diplomatic benefits, crude as the tactic may be.

At the popular level, Britain has sought solace in history. It has put up statues of Gandhi, extolled India’s role in the World Wars, and incessantly debates questions of colonialism, historical guilt and the value of national apologies. But this cultural vocabulary is itself out of date. Few Indians treat these issues as priorities. Over one-quarter of Indians actually think that their country fought against Britain in the First World War. Modi’s predecessor Manmohan Singh, prime minister until last year, was in some ways a product of England, attending Cambridge and Oxford in the 1950s and 60s. In a memorable 2005 speech delivered at Oxford, Singh argued that ‘elements of fair play … characterised so much of the ways of the British in India’ and that ‘even at the height of our campaign for freedom from colonial rule, we did not entirely reject the British claim to good governance’.

The point is not that Modi, the first Indian prime minister born after independence, disagrees; it is that his framing is entirely different. Speaking to the Indian diaspora in New York’s Madison Square Garden last year, Modi famously lamented that ‘we were under slavery for 1,000-1,200 years’, implicitly relegating all Muslim dynasties – above all, the Mughals – to the status of alien occupiers of Hindu India, but also demoting the Raj to a late millennium footnote and therefore the fringes of his demonology. Modi will therefore see the 60,000 adulatory British-Indians gathered at Wembley Stadium on Friday evening as diplomatic assets to be leveraged, not some romantic thread connecting two intimately bound nations.

This should not overshadow what is likely to be real diplomatic progress on defence, development, energy, climate change, trade, and investment. Modi will be eager for respite from his domestic political travails, having heavily lost a local election and under intensifying fire for passivity in the face of religious intolerance and tension. The UK will emphasise headline grabbing, if routinely inflated, figures for trade and investment deals. It can also boast that on economic and social ties, it remains well ahead of Paris or Berlin. But, when the inevitable faux-chummy Modi–Cameron selfies and tweets fade, the question remains: what is truly ‘strategic’ about the partnership?

WRITTEN BY

Shashank Joshi

Advisory Board Member