In His New Government, Lula’s Pragmatic Economics are Set to Depend on China

With forecasts for growth deceleration looming in the region, Brazil’s incoming president will favour long-term investments with Beijing.

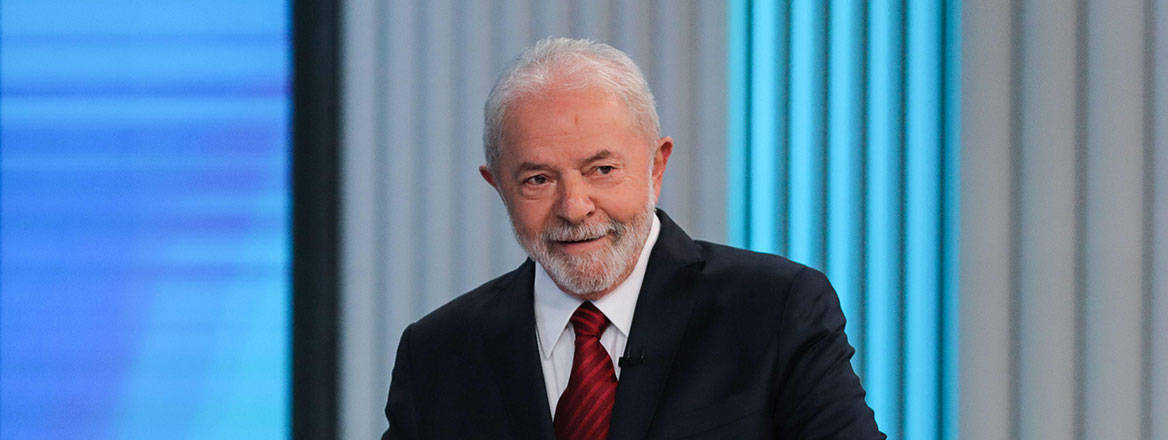

September and October were busy months for Chinese importers of soybeans. Asian buyers went on a shopping spree in the US, Argentina and Brazil, building stockpiles for the internal market ahead of the holiday season. Brazilian producers were keen to sell their harvest since the weather had not been the best for crops, and sales were stumbling. For the market and the president-elect, the iconic left-winger and 76-year-old Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, China’s appetite for imports is terrific news.

Lula da Silva’s incoming government (2023–27), with one consecutive re-election opportunity, is set to navigate through a sluggish growth period. The need to deliver on fiscal reforms will tie down the Brazilian trade relationship with China for the next decade. Despite some doubts about the future of the Sino-Brazilian partnership, the signals for more interdependence are loud and clear.

A study published by the Brazil-China Business Council (CEBC) in September showed that new investments made by Chinese companies in Brazil more than tripled in 2021, making the country the leading destination in the world for capital coming from China. A total of 28 new projects added $5.9 billion, an increase of 208%. On the contrary, Chinese investments in other destinations, such as Australia and the US, fell during the same year.

Lula’s main challenge will be its growing exposure to a Chinese slowdown. Foreseeing this, the left-winger campaigned heavily on his track record of leading Brazil through the global recession of 2008–10 during his first stint at the presidency (elected in 2003 and re-elected in 2006). Many Brazilians give him credit for handling trade policy, chiefly his capacity to sell pricey commodities and bring more dollars to the public purse.

It remains unclear whether he will be able to outperform himself to keep financing expensive social programmes such as Bolsa Família for the poorest Brazilians. As well, his tight win in the runoff election and the presence of hard-Bolsonaristas (followers of outgoing president Jair Bolsonaro) in the opposition gives him little room to manoeuvre his proposed fiscal reforms among political forces in Congress.

Unpredictable Economic Scenario

The volatile external environment that is likely in 2023 will impact Lula’s public policy plans which include, among other large-scale reforms, a restructure of the public administration system, which remains vastly underpaid compared with the private sector, and agrarian reform to promote jobs for a growing lower-middle class.

Brazil enjoys a healthy trade balance with China (see graph). However, Chinese purchasing power adds uncertainty in the trading relationship. Lula hopes that, for his tenure, the country sustains this year’s record foreign direct investment levels and an economic growth rate estimated at around 2.5% for 2023. Signals of a global recession could inevitably bring down prices of Brazil’s top exports, including oil and agricultural commodities. Brazil’s exports depend on whether infrastructure projects in China will demand more of the country’s critical commodities for large property markets, such as steel and iron ore.

Brazilians have generally been affected by high inflation, which was recorded at an annualised rate of 8.7% in August, just like many other economies in the world. Lula will have to decide whether to stick with Bolsonaro’s policy interventions (that is, subsidies for fuel and electricity prices and other sources of disinflation) or propose some measures of his own. Another challenge for Lula will be deciding whether the current wave of privatisation and concessions will continue under his mandate. Bolsonaro’s preference for the private sector to run large companies once owned by the state does not bode well with Lula’s ‘Carta para o Brasil do Amanhã’, his roadmap for fiscal responsibility and state control in key public services. Lula’s closest consigliere in economic policy, Henrique Meirelles, is a former central bank chief considered a moderate towards market intervention. Against the advice of his party, Lula is inclined to an independent Central Bank.

New and Old ‘Lulismo’

In his attempt to double down on Chinese investments, Lula will have to rekindle Sino-Brazilian relations which went cold during Bolsonaro’s government. Celso Amorim, Lula’s ex-foreign minister, said earlier this year that China–Brazil ties would boost if Lula won the election. Surprisingly, Lula has sent ambivalent messages towards Beijing, one day blaming China for predatory industrial practices and the next embracing their so-called strategic relationships in trade, scientific and cultural relations.

During Brazil’s golden era of diplomacy, Brasilia and Beijing challenged global economic powers forging the BRICS group of emerging economies and agreeing on common causes, such as opposing the US-led invasion of Iraq. During his first presidency, Lula said that travelling to Beijing to meet his comrades from the Chinese Communist Party was his most important visit abroad.

In this author’s view, Bolsonaro helped to pave the way for China’s inroads in Brazil, and Lula will keep riding in the same direction. Pressured by ways to augment Brazil’s exports to the world, Bolsonaro decided to stay out of the US–China trade war and let Brazil ‘trade with the entire world’, including Russia, India and South Africa. It is expected that Lula will return to his old diplomatic ways. During the campaign’s closing events, he brought with him to the stage the 87-year-old former Uruguayan president, José ‘Pepe’ Mujica, a contemporary of the ‘Pink tide’ of leftist presidents that dominated the region in the mid-2000s. Mujica also fell for Chinese monies and sought significant investments in ports and railways from Beijing. Lula will also try to revamp the Southern Common Market (Mercosul in Portuguese) with Argentina, Paraguay and Uruguay, bringing it closer to China. On the same track, he will aim to revive the prolonged EU–Mercosul free trade agreement.

Undoubtedly, the current left-wing presidents in Chile, Argentina, Colombia and Mexico will welcome Lula’s arrival and celebrate Bolsonaro’s loss. This works very well for China. Beijing knows that Lula will try to extend links and propose a soft-power approach to make anti-US foreign policy in the region shine again. Chinese diplomats in Brasilia have been vocal in extending President Xi Jinping’s wish for a ‘deep development of the China-Brazil Global Strategic Partnership’, a new deal that facilitates Beijing’s investments in Brazil and promotes Chinese manufacturers (around 90% of Brazilian purchases) to the local market. Around this framework, the Chinese Great Wall Motor Group announced a $1.8-billion investment to open an electric vehicle assembly line in the state of São Paulo. In a smart move, Beijing appointed Zhu Qingqiao as ambassador to Brazil, a senior diplomat who knows the region well after holding the same post at the embassy in Mexico City.

Preservation or Industrialisation?

The outgoing Jair Bolsonaro turned the Brazilian government into a world pariah given his ugly record on climate change, women and gender minorities' rights, and overall disrespect for independent public institutions, such as the courts of justice. It will be up to Lula to steer the country in a new direction. His curriculum is tainted by the corruption scandals that unfolded in his previous government. His respect for democracy at home, however, brings some certainty.

Nonetheless, new problems will emerge. How will Lula deal with the authoritarian practices of China, its biggest trade partner, and how will he be able to enforce sustainable development at home? Lula’s policies to combat deforestation and illegal resource extraction in the Amazon will remain under intense scrutiny by international and local organisations monitoring environmental laws. China’s food security programme demands produce farmed in the Amazonia region. Soy farmers, gold miners and cattle ranchers have expanded to protected areas where biodiversity is in peril, and indigenous populations are pressured to leave their land. Lula was favoured among green voters and job-seeking younger generations. His old track record backing hydroelectrical projects make many ask whether he will strike a balance between preservation and industrialisation. For this purpose, the Chinese factor adds more questions than answers.

The views expressed in this Commentary are the authors’, and do not represent those of RUSI or any other institution.

Have an idea for a Commentary you’d like to write for us? Send a short pitch to commentaries@rusi.org and we’ll get back to you if it fits into our research interests. Full guidelines for contributors can be found here.

Dr Carlos Solar

Senior Research Fellow, Latin American Security

International Security

- Jim McLeanMedia Relations Manager+44 (0)7917 373 069JimMc@rusi.org