Harnessing Industry for Energy Security and Resilience

Demand flexibility will increasingly take centre stage in energy security. Can industry play a role while contributing to industrial development?

Today, imported natural gas underpins the UK’s energy security strategy. The UK’s ambitious Clean Power 2030 Action Plan (CP2030) intends to reduce this dependency by delivering an electricity system that uses only 5% unabated natural gas by 2030, with 95% clean power - that includes renewables, nuclear, low carbon dispatchable (hydrogen and Carbon Capture and Storage(CCS)) supported by storage, interconnections and consumer-led flexibility.

However, as a transitional measure to support energy security, CP2030 retains 35GW of unabated gas capacity. In future, system reliability and energy security must reflect an increasingly electrified and variable system, which will make flexible energy consumption increasingly important. Indeed, demand flexibility may be one of the quickest ways to increase security while reducing energy costs.

CP2030 cannot sacrifice industrial competitiveness. A key challenge highlighted in the Invest 2035 Industrial Strategy is that UK electricity prices are higher than European countries like Germany and France. Meanwhile, in 2023 industry accounted for 27% of the UK’s electricity demand. Around 70% of electricity consumption from industry was supplied by the grid, with an additional 20% from combined heat and power (CHP), and 10% from onsite generation. Industry could be incentivised to play a bigger role in securing the CP2030 system with solutions that also support lower industrial energy costs.

CP2030 cannot sacrifice industrial competitiveness. A key challenge highlighted in the Invest 2035 Industrial Strategy is that UK electricity prices are higher than European countries like Germany and France. Meanwhile, in 2023 industry accounted for 27% of the UK’s electricity demand. Around 70% of electricity consumption from industry was supplied by the grid, with an additional 20% from combined heat and power (CHP), and 10% from onsite generation. Industry could be incentivised to play a bigger role in securing the CP2030 system with solutions that also support lower industrial energy costs.

In 2024, less than 27% of UK electricity generation was from unabated natural gas or coal, and at 30%, wind became the largest source of electricity generation. The UK electricity system can manage high levels of variable renewables; the challenge is having enough low carbon generation – such as wind, solar, biomass, hydropower, nuclear, imports and storage – when needed. Multiple solutions are needed, for example, to manage multiple dark days without wind as well as within-day variability.

Figure 1.1 illustrates the monthly, daily, and within day share of low carbon generation in the electricity mix. The first chart shows the day with the lowest share of low carbon generation and the day of the highest share of low carbon generation for each month in 2024. The gap between the two lines shows the variability in that month. The biggest variability is in November, December, and January when there are dark days with little wind.

Figure 1.2 shows the daily percentage of low carbon generation in January and July. In the summer, electricity from solar increases and this generation profile is complementary to wind. Adding more wind and solar will shift the lines up, but there will still be a gap, particularly in the dark winter months. Reducing this requires more dispatchable (generation that can be turned on and off) low carbon sources, long-duration storage, or adjusting demand to match electricity availability.

Figure 1.3 shows within-day variability. The electricity system has managed 95% from low carbon generation sources and will be able to manage 100% when available in 2025 through digital operations, system services, interconnections, batteries, load following of hydropower, and demand response.

In the winter of 2022/2023, the demand flexibility service (DFS) enabled consumers and businesses to shift or reduce over 3,300MWh of electricity, reducing demand at key times. In the winter of 2023/2024, DFS was successfully adapted to allow more participation from commercial consumers. In CP2030, demand response is expected to provide 10-12GW of flexibility. Industrial facilities are already among the service providers in DFS, but there is much more potential.Given 61% of demand is industry, commercial, or energy industry, consumer-led flexibility capacity from these consumers will be critical in matching demand to supply in periods of system stress.

Although the increase in variable renewables should not increase total electricity costs, one result of Figure 1 is a change in the share of commodity vs. non-commodity electricity costs, with commodity costs (wholesale electricity prices) going down and non-commodity (e.g., system services, delivery, policy) costs going up. For example, constraint management is expected to cost £500 million to £3 billion/year, most of which is redirecting or turning off renewable power. Capacity market charges are also a significant non-commodity cost: the last T4 auction cleared at £65/kW.

Design system services and capacity markets with energy-intensive industry in mind

System services could better reflect the characteristics of industrial consumption: supporting industrials in stacking revenues (in other words, earning revenue and delivering multiple system services from the same asset simultaneously), reducing peak demand, and even participating in capacity markets.

“By working with industrial and commercial consumers to optimise demand loads (leveraging energy efficiency, storage, and other technologies) so the consumption profile is in harmony with the generation profile, demand flexibility can improve resiliency and be a risk management tool.”

Cathy McClay, National Grid DSO

Industrial facilities, particularly in energy-intensive sectors, have distinct constraints – such as continuous processes or temperature-sensitive production – but also hold significant potential to contribute to system flexibility. By designing demand-side mechanisms that recognise these operational realities, industry could participate more effectively while maintaining both operational and financial stability.

An ongoing research project by MIT, Accenture, and an industrial cluster in Spain is examining the potential for industrial demand management and flexibility. The study reviewed Spain’s Servicio de Respuesta Activa de la Demanda (SRAD) programme, a structured but initially underutilised demand response mechanism. Industrial participation was limited in the early stages due to uncertainty regarding interruption expectations and a misalignment with planning cycles. Engagement increased once the programme introduced clear expectations on interruption duration, structured compensation models, and well-defined activation timelines, ensuring flexibility requirements were predictable and could be integrated into business planning.

A key finding from this research is that industrial flexibility mechanisms are more effective when they accommodate partial load reductions rather than requiring full facility shutdowns. For instance, forthcoming research conducted by SPRI and Accenture found that in the cement sector mills accounting for a substantial share of a plant’s energy consumption were curtailed while furnaces remained operational, allowing participation in demand response without compromising core production processes.

"By aligning flexibility mechanisms with industrial needs, we enhance energy efficiency, reduce emissions, and strengthen long-term competitiveness while ensuring industries play a central role in the clean energy transition"

Cristina Oyon, Deputy Director General of Grupo SPRI, Economic Development, Sustainability and Environment Department of the Basque Government.

The UK could enhance industrial participation in flexibility markets by supporting industry to integrate demand response into operational planning, for example, leveraging planned maintenance cycles and scheduled downtime to incorporate flexibility in routine operations; annual MW commitments with minimum and maximum participation thresholds to provide the certainty needed to align curtailment with operational requirements; and tiered activation notice periods, ranging from short-term response to day-ahead scheduling, to allow different industries to engage based on their ability to adjust operations within given timeframes.

The growth in electrification of industrial processes supported by initiatives like Make UK’s Electrify Industry and incorporation of the electrification of fleets and heating (including renewable CHP, heat pumps, and emerging power-to-heat technologies) adds further optimisation opportunities.

Incentive frameworks also need to reflect commercial realities. Conducting sector-specific financial break-even assessments for production adjustments would help tailor incentives to industrial constraints, making flexibility an attractive option rather than a risk to production continuity.

Use industrial clusters to optimise industrial electricity consumption, storage, and infrastructure development.

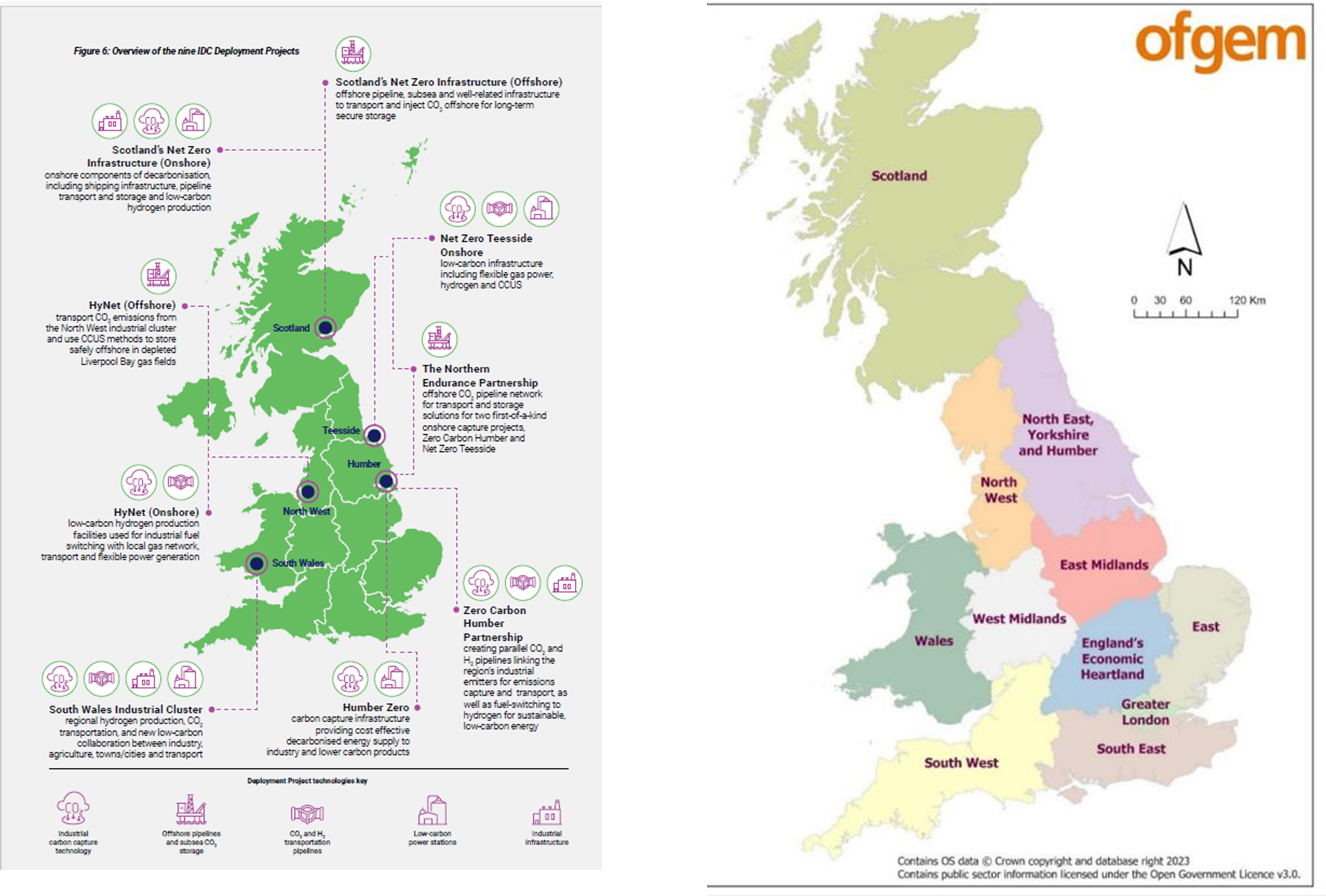

Industrial clusters are a core part of the UK’s industrial strategy. Although the UK’s industrial cluster approach has focused on CCUS and hydrogen, renewables and grid investments are already part of the cluster plants (e.g. offshore wind in Humber). NESO is trialling a Local Constraint Market in one of its most constrained boundaries to access new sources of flexibility. This could go further to include industrial facilities and fleets in constrained areas. Organisations like Regen have proposed ‘collaborative power pools’ to allow clusters and regions to procure energy under longer-term power purchase agreements (PPAs).

Figure 2 shows the location of the industrial clusters and the electricity planning regions. The UKRI CCS and Clean Hydrogen Cluster Approach could be adapted for Clean Power 2030, for example with a competition for established clusters and distribution system and network operators to develop electricity cluster plans that optimise storage, local and/or co-located low carbon generation, infrastructure development, synergies between electricity and heat and transport, system services, peak power reduction, and capacity market participation to reduce electricity costs and support Clean Power 2030.

“We have to be pragmatic. We should not necessarily allow policy constraints to over-ride what is technically possible and which would support more efficient delivery of Clean Power [2030] – e.g., the 100MW limit on private wire transfers. We should also aim to maximise efficiencies of power across industrial clusters, which could include such steps as thoughtful co-installation of pipelines and cables to better connect clusters for a lower-carbon future.”

Jonathan Oxley, Executive Director, Humber Energy Board

In addition to capital project efficiency, there is an opportunity to bring industry flexibility and regional resiliency into the planned work developments during the development of the Local Area Energy Plans (LAEPs), the NESO Regional Energy Strategic Plans, and in the creation of new industrial clusters/groupings through programmes like the Local Industrial Decarbonisation Plans Competition.

Other markets are exploiting cluster opportunities. Since May 2018, Dublin Airport Authority (DAA), the airport operator, has been participating in Ireland’s DS3 (‘Delivering a Secure, Sustainable Electricity System’) programme. With the support of Enel X, DAA contributes more than 8MW of flexible capacity into EirGrid’s ancillary services programme by leveraging its energy assets. DAA is remunerated for its services and, by utilising their assets regularly, they improve the resilience of their operations. Airports are useful for energy security as their loads typically run countercyclical to a weather event.

With demand growth from new loads (for example, data centres/AI hyperscalers, carbon capture plants), new sources of flexibility (for example, cooling of data centres), growth in onsite solar and renewable CHP, and the electrification of heat and fleets, there will be synergies between bottom-up local and regional solutions and top-down whole system planning

“The industrial sector is an important partner in delivering a Clean Power 2030 that supports competitiveness and growth. We want to work with industry and regions/clusters, so they have access to reduced electricity costs while improving the reliability, resiliency and security of the electricity and wider energy system.”

Fintan Slye, Chief Executive, National Energy System Operator

Industrial facilities are large demand centres that can also be generation, storage, and flexibility centres. There are opportunities to design system services products that match the operational realities of industrial facilities to reduce peak demand. Regional models could be leveraged to find synergies that will reduce electricity costs and reward industry while supporting a clean power system, for example, where on-site storage, local or on-site generation, and shared infrastructure could support thermal constraints, congestion challenges, demand growth, and system resiliency and security. These measures would potentially quite quickly build resilience into the energy system and to industrial operations, improving the ability of the system to cope with shocks and supply constraints.

“Flexible demand is too often overlooked as an enabler of progress towards a cheaper power system, which can accommodate variable renewables at scale. We have set an ambition for 12GW of consumer-led flexibility by 2030, in line with NESO advice. Since most electrical demand is industrial and commercial, this is now a critical component of government’s 2030 ambitions. Non-domestic consumer-led flexibility has fallen recently, reducing from 1.7GW in 2021 to 1.2GW in 2022 and then to 0.8GW in 2023. We see steps to support more flexible industrial demand, from industrial clusters and possibly data centres too, as key to reversing this recent trend.”

– Chris Stark, Head of UK’s Mission for Clean Power, UK Department for Energy Security and Net Zero

© Melissa Stark, 2025, published by RUSI with permission of the author.

The views expressed in this Commentary are the author's, and do not represent those of RUSI or any other institution.

For terms of use, see Website Terms and Conditions of Use.

Have an idea for a Commentary you'd like to write for us? Send a short pitch to commentaries@rusi.org and we'll get back to you if it fits into our research interests. View full guidelines for contributors.

WRITTEN BY

Melissa Stark

Guest Contributor

- Jim McLeanMedia Relations Manager+44 (0)7917 373 069JimMc@rusi.org