Failing to Understand Adversaries Creates a Vicious Circle of Tensions

Tensions can escalate quickly when adversaries fail to understand each other. Unfortunately, we are often least able to understand our adversaries when tensions are high. Breaking this cycle is essential.

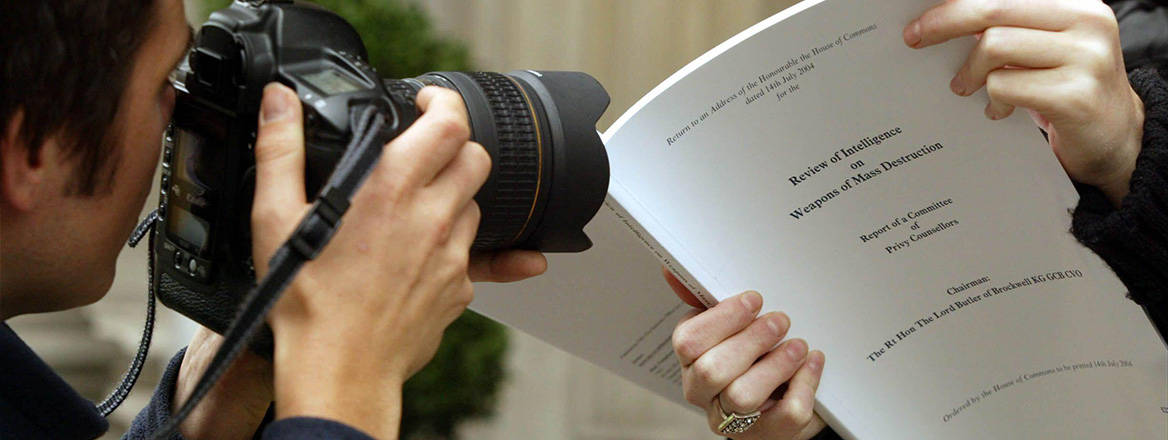

Iran and Israel’s escalation of their armed conflict is a reminder of what can happen when adversaries do not understand each other. It is exactly 20 years since Lord Butler and the four other members of his Committee of Privy Counsellors wrote their Review of Intelligence on Weapons of Mass Destruction. Announced by then Foreign Secretary Jack Straw on 3 February 2004 and published only five months later on 14 July 2004, the Review is a succinct and rich document which recounts – with many cautionary tales – how the arguments for war with Iraq began and became embedded in the preceding decade. It provides a perfect case study for how the threat of war becomes war, how initial judgements become baseline assumptions over time, how difficult it can be to look for a threat which may or may not be there, and how this is made more difficult when the threat actor wants to appear threatening in order to deter an attack.

The Committee’s purpose was to investigate the extent of intelligence coverage of WMD, to investigate the accuracy of intelligence on Iraqi WMD up to March 2003, to examine any discrepancies between the intelligence gathered, evaluated and used by government before the conflict and what has subsequently turned out to be the case, and to ‘make recommendations to the Prime Minister for the future on the gathering, evaluation and use of intelligence on WMD, in light of the difficulties of operating in countries of concern’.

Much has been made of the Review’s recommendations both in terms of techniques of collection, review and analysis, and in terms of structure: the recommendations re-set the doctrine for the production, issuing, analysis and assessment of intelligence, and the relationship between assessment and policy. Much less has been made of another of the Review’s observations, hidden away on page 112, that the Joint Intelligence Committee (JIC) ‘may, in some assessments, also have misread the nature of Iraqi governmental and social structures. The absence of intelligence in this area may also have hampered planning for the post-war phase on which departments did a great deal of work’.

At times of high stress, it is natural and instinctive to focus on the most acute elements of a threat in order to defend against it

The Review attributes this gap to the fact that collection of intelligence on Iraq’s prohibited weapons programmes was designated as being a JIC First Order of Priority whereas intelligence on Iraqi political issues was designated as being Third Order. In practice that meant huge effort and resource was devoted to answering the very particular question of whether Saddam Hussein had WMD and, if so, where, and much less to the broader question of how and what he ruled. This gap, between the focus on the explicit and immediate threat and the broader understanding of the adversary in all their complicated aspects, is just as relevant today. At times of high stress, it is natural and instinctive to focus on the most acute elements of a threat in order to defend against it.

Two other factors exacerbate this. First, knowledge and understanding of the other plummets as battle lines harden. Defences are raised, walls built, embassies closed and emissaries sent home. This is a vicious circle, since adversaries then understand each other even less, which means an increase in the risk of miscalculation and misinterpretation.

Second, threatening language is increasingly being used to conduct foreign policy. It is conflated with the idea of ‘deterrence’, but of course threatening rhetoric can be escalatory rather than deterring. If you think you are going to be attacked it is natural to want to make yourself look as dangerous as you can, like a cat arching its back. Saddam Hussein wanted to appear threatening to make an attack against Iraq less likely. The US saw a threat and decided it needed to act before that threat materialised.

Saddam Hussein wanted to appear threatening to make an attack against Iraq less likely

How to respond to aggressive posturing by the adversary is a critical foreign policy judgement. But the lesson embedded deep within Lord Butler’s report is the danger of not understanding your adversary enough, and the mistake is to attribute this entirely to a lack of intelligence, which will always be a limited resource and focused on the most dangerous threats. The question is how to ensure decision-makers have the broadest possible understanding of the social, economic, political and cultural forces influencing the actions of the adversary. This could, and should, come from other departments of government, but it is also critical that outside voices – often with greater understanding or different perspectives (particularly historical ones) – are heard.

It is typical when estimating a threat to assess both capability and intent. One’s understanding of the adversary’s capabilities can be right or wrong, since it is an estimation of fact based in the past and the present. But the adversary’s intent depends on their likely choices, decisions and constraints, and is looking to the future. At times, therefore, of heightened risk, the real requirement is for an understanding of the risk calculus of the opponent, and what might change it. By the same token, it is important to factor in the chance that this same opponent may also be mistaken in their interpretation of the threat. It is vital, therefore, to have not only a deeper understanding of the adversary, but also a greater awareness of how one’s own actions are perceived and the responses they might prompt.

The views expressed in this Commentary are the author’s, and do not represent those of RUSI or any other institution.

Have an idea for a Commentary you’d like to write for us? Send a short pitch to commentaries@rusi.org and we’ll get back to you if it fits into our research interests. Full guidelines for contributors can be found here.

WRITTEN BY

Suzanne Raine

RUSI Trustee

- Jim McLeanMedia Relations Manager+44 (0)7917 373 069JimMc@rusi.org