New safety in custody statistics in adult and youth prisons underline the crisis in our offender management system.

The prison system in England and Wales is in crisis. Self-harm in prisons is at a record high, with worrying spikes in violence over the past 12 months. The National Probation Service is struggling to provide adequate rehabilitation and community supervision services to offenders post-release, with staff shortages meaning that most staff are failing to meet their weekly caseload targets. The government has now made it a priority to create thousands more prison spaces. But unless substantial resources are also invested both in prison safety and the services available to offenders post-release, these measures will do little more than place thousands of offenders into a dangerous and violent environment, with little prospect of rehabilitation or reform.

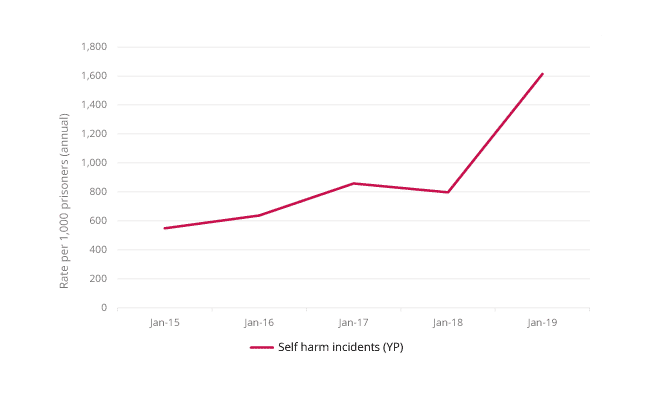

On 30 January, the Ministry of Justice released new ‘safety in custody’ statistics covering deaths, self-harm and assaults in the prison system. The number of individuals self-harming in prison in the 12 months to September 2019 is now at 12,740 – the highest recorded figure. In that period, there were 61,461 self-harm incidents (a rate of 742 per 1000 prisoners), up 16% from the previous 12 months, and also a new record high. In female establishments, these figures are particularly shocking: a rate of 3007 incidents per 1000 prisoners represents an increase of 18% in the last 12 months. Most concerning of all, in ‘youth estate’ – 15- to 18-year olds in Young Offender Institutions and all 15- to 17-year olds in Youth Prisons – there was a 93% increase in self-harm incidents in the 12 months to September 2019 (from 551 to 1,062 incidents). Incidents requiring hospital attendance increased from 2.5% in the previous 12 months to 4.8% in the 12 months to September 2019.

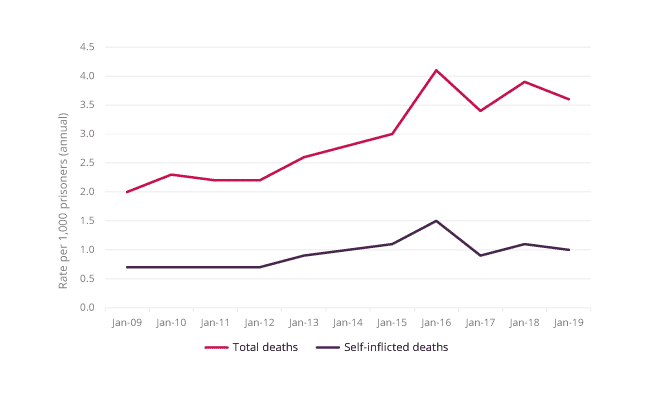

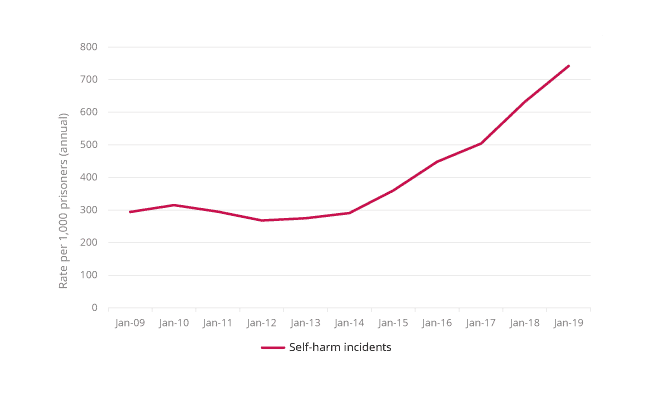

As worrying as these 12-month figures are, there is more cause for concern when these figures are viewed in a longer-term context.

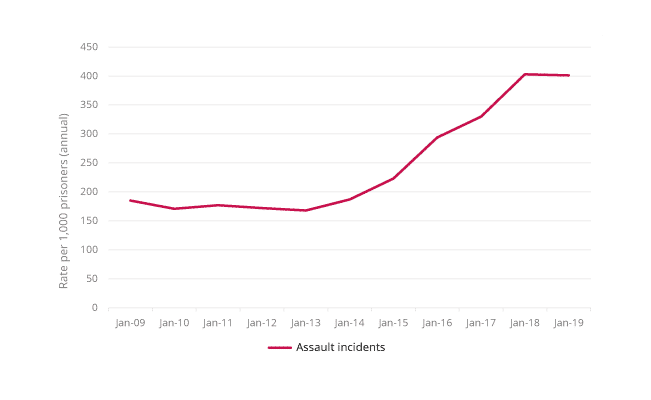

The four graphs below illustrate this point.

Figure 1 displays the 10-year trajectory of the rate of deaths per 1000 prisoners from 2009 to 2019. In 2009, this number was roughly 2.0, and by 2019 it had risen to around 3.6. With self-harm in adult prisons, Figure 2 illustrates an almost linear increase from 300 incidents per 1000 prisoners in 2009 to 742 per 1000 prisoners in 2019. A similar story presents itself in Figure 3 with youth self-harm rates over 6 years. Assaults that had decreased by 2% to 33,222 in the 12 months to September 2019, are shown in Figure 4 to have risen from a rate of around 190 per 1000 prisoners in 2009 to 400 per 1000 prisoners in 2019.

The information outlined here poses serious, urgent challenges for government. Last August the Prime Minister promised to create thousands more prison places in a system currently operating at 98% of capacity, supported by Justice Secretary Robert Buckland QC’s insistence that ‘more and better prison places means less reoffending’. This directly contradicts the Ministry of Justice’s (MOJ) own research (backed by previous Justice Secretary David Gauke), which suggested that ‘sentencing offenders to short-term custody with supervision on release was associated with higher proven reoffending than if they had instead received community orders and/or suspended sentence orders’.

The most recent MOJ statistics show that the proven reoffending rate for adults released from custodial sentences of less than 12 months was 62.7%. Far from reducing reoffending, the majority of people imprisoned for less than 12 months will offend again within a year. The recommendation for sentences less than 6 months to be abolished was promptly ignored by the Prime Minister, setting the tone for an agenda on crime and prisons policy that has side-lined rehabilitation and re-integration.

But the problems run much deeper than the prisons system. The probation service is also failing to provide adequate services to offenders once leaving prison, meaning many remain locked in the cycle of re-offending. A recent inspection report from HM Inspectorate of Probation found that adoption of ‘accredited offending behaviour programmes’ – these are programmes judged by a panel of independent experts to satisfy principles of effective rehabilitation – had substantially decreased. Alongside this, caseworkers were found to be lacking in support from HM Prison and Probation Service to understand individual characteristics of offenders and incorporate these insights into their programmes. This, in turn, has repercussions on which programmes end up being authorised in the first instance, and on the extent to which those programmes are seen as accessible by the offenders that they are targeting. The report also confirmed the worrying anecdotal evidence increasingly coming to light concerning staff well-being in the National Probation Service (NPS). Over 60% of staff have caseloads exceeding the recommended maximum, while new recruits are being allocated complex cases without the skills or experience to manage them – partly explaining the significant problem of staff retention in the NPS.

In January two new statutory instruments were brought before Parliament, proposing significant changes in the management of serious violent and sexual offenders. Specifically, the proposed legislation will require offenders to serve at least two-thirds of their sentence in prison (as opposed to half-way release), before they are subject to strict licence conditions upon release. While the authorities are still to release further accompanying details, it appears doubtful that these punitive measures will align with additional investment in community supervision, rehabilitation and re-integration programmes.

A combination of extreme workloads and reduced capacity has abetted the mismanagement of offenders in the criminal justice system and created a climate of distress where the conditions for increased deaths, self-harm, and assaults in prisons are rife. This inherently damages the chances of offenders embarking upon a journey of self-improvement once entering the criminal justice system, thereby increasing the likelihood of further reoffending upon release.

Simply creating more prison spaces is unlikely to address these issues, unless this is accompanied by substantial resource investment in programmes focused on the rehabilitation and re-integration of offenders both while in prison and post-release. It is only by first understanding what methods of offender management work with which offenders, why they work, in what contexts, under what conditions, and what outcomes they produce that we can begin to deal with the spiralling problem of safety and well-being amongst people in the criminal justice system.

Ardi Janjeva is a Research Analyst in organised crime and policing at RUSI.

The views expressed in this Commentary are the author's, and do not represent those of RUSI or any other institution.

WRITTEN BY

Ardi Janjeva

Former Research Fellow