Is Defence’s Latest Operating Model Fit for Purpose?

The Ministry of Defence has published a new version of its operating model – ‘How Defence Works’ – its first update for almost five years. Given the major changes to Defence ways of working in that time, and the forthcoming Integrated Review’s potential for further disruption, is it, and how long will it remain, fit for purpose?

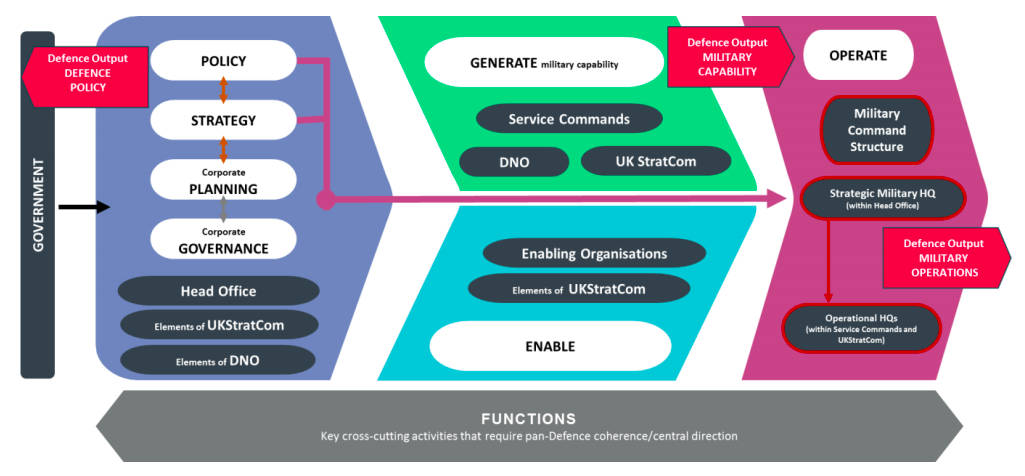

Recently, the Ministry of Defence (MoD) issued an update to the 2011 ‘How Defence Works: The Defence Operating Model’ report, which first introduced its ways of working, following its ‘Defence Reform’ report (commonly known as the Levene Reforms). For the first time, the Department has deviated from the operating model principles laid down by Lord Levene. Specifically, it has moved from the six functions originally used to describe Defence’s outputs, to seven ‘core activities’: policy; strategy; planning; governance; generate; enable; and operate. In turn, these outputs are now described in three broad categories:

- Working with other parts of government to develop Defence Policy in support of National Security Objectives.

- Military Capability – development of the ability, both now and in the future, to have military influence and project force.

- Military Operations – using the armed forces to support specific government goals and undertaking ongoing military tasks such as operating the UK’s nuclear deterrent.

These changes are reflected in the amended schematic below. It is, however, unclear whether the MoD’s new operating model will solve some, or all, of the problems inherent in its predecessor that were identified in the recent RUSI Occasional Paper, ‘Management of Defence after the Levene Reforms’.

Figure 1: The Defence Operating Model, 2020

Accommodating Tensions Within the Operating Model

The greatest challenge for any business operating model is how to balance the inevitable tension between those responsible for delivering specific outputs and those responsible for managing the organisational-wide processes that support and constrain all outputs. For instance, large institutions tend to set binding rules for activities such as recruitment and financial management. In every version of the Defence Operating Model to date, top-level budget (TLB) holders – as the deliverers of military capability – have been given primacy. This stems from Levene’s key assertion that the service chiefs must be focused on running their services and empowered to perform their role effectively. Although past iterations of the operating model also attempted to provide custodians of the cross-cutting activities sufficient authority to maintain efficient and effective Defence-wide processes, they were never successful. The reason for this was that, because the TLB holders owned all the resources (principally finance and people), they had the power to, at best, pay lip-service to the cross-cutting processes, or, at worst, ignore them completely.

By aligning with the government’s wider Functional Model, ‘How Defence Works’ version 6.0 may have eased this problem. In short, each cross-cutting function is led by a three-star Functional Ownerwho is responsible for cohering their function Defence-wide. The MoD is implementing Functional Leadership for all core government functions (for example, commercial and digital), as well as a number of additional, Defence-specific activities (for example, intelligence and support). It is too soon to tell if this approach will be successful, but by recognising the functions as an integral part of the operating model, cross-cutting activities have been significantly elevated. Furthermore, by including the Functional Owners’ outputs as part of MoD Head Office’s responsibilities and mandating that resourced functional objectives are detailed in the Defence Plan, the Department has gone a long way to resolving one of the operating model’s biggest issues.

Accepting a Rules-Based Operating Model Construct

In his ‘Foreword’, the MoD’s Permanent Secretary, Stephen Lovegrove, confirmed that ‘How Defence Works’ remains the authoritative statement of how the Department is to operate, aimed at both an internal and external audience. However, at 38 pages, it is considerably shorter than its predecessor, and its focus has essentially been reduced to a high-level description of how Defence is organised and a broad-brush description of how Defence outputs are delivered. It is recognised that, within a department that has so many chiefs, gaining consensus on a rules-based construct will never be easy; nevertheless, the latest version of ‘How Defence Works’ is neither convincing nor complete. For example, although the document states that the Defence Operating Model explains how the MoD works with industry and international partners, it does not. Moreover, while it includes the intent to ‘clarify and strengthen governance within Head Office’, a clear explanation on how that should be achieved is not forthcoming. If the Defence Operating Model is to be authoritative, it must contain unambiguous rules on how the MoD’s constituent parts (Head Office, the three armed forces, Strategic Command, the Defence Nuclear Organisation, and enabling organisations) operate together, as well as clear direction on how the Department integrates with the rest of government, and interacts with external organisations.

Aligning with Other Defence Initiatives and the Integrated Review

In the run up to the announcement of the Integrated Review, the MoD has been releasing important policy documents. In a high-profile event at the end of September, Chief of the Defence Staff, General Nick Carter presented Defence’s new Integrated Operating Concept. This was followed soon after by the Secretary of State for Defence, Ben Wallace, announcing the Science and Technology Strategy 2020. Both documents shared a distinctive new style of branding and their launches attracted wide media coverage. In contrast, the new version of ‘How Defence Works’ made do with old branding, was only promulgated as a routine announcement on the MoD’s daily update page on the gov.uk website, and attracted no media coverage. One can only speculate why, but the update seems totally misaligned with the Department’s Integrated Review influence campaign.

A final point to be considered is the potential impact of the Integrated Review itself, now due to conclude early next year. Although defence spending is set to increase by £24.1 billion over the next four years, and Prime Minister Boris Johnson has already announced a number of new initiatives, for example the establishment of a centre dedicated to artificial intelligence, the review’s findings could still fundamentally transform Defence outputs. Moreover, given the fondness of many in government for headline-grabbing announcements, it would be surprising if there were no major changes to the Defence force structure and/or its ways of working. To that end, the timing of the latest version of ‘How Defence Works’ must be questioned. As a necessary, but nevertheless bureaucratic document, it will always react to change rather than drive it. Therefore, MoD Head Office may soon find itself faced with the need for a substantial rewrite.

Conclusion

In the nine years since the ‘Defence Reform’ report was published, its recommendations have become thoroughly embedded in the way the MoD works. However, in deviating from Levene’s original operating model principles, the latest version of ‘How Defence Works’ shows that the MoD is prepared to develop its business-management thinking and evolve its business practices. In addition, by embracing the government’s wider Functional Model, it has shown a willingness to tackle the model’s thorniest problem.

Although these are both positives, they cannot hide failings elsewhere. The lack of alignment with other key Department documents, and the questionable timing of its release, suggest that ‘How Defence Works’ may not have buy-in from the highest levels of MoD Head Office. Moreover, its lack of both substance and authority means it is unlikely to be taken seriously across Defence, and, therefore, there is a real danger it may simply end up as ‘shelfware’.

Ultimately, ‘How Defence Works’ exists to provide the rules for how Defence should operate and, in an organisation with so many chiefs, it is definitely needed. That said, on its own the document is no more than a collection of words and diagrams. Even the best-written and most authoritative Defence Operating Model requires leadership from the very top of MoD Head Office to bring it to life, and, more importantly, support from the military commands and the enabling organisations to ensure it is followed. Without that, it will never be fit for purpose.

The views expressed in this Commentary are the author's, and do not represent those of RUSI or any other institution.

WRITTEN BY

Air Commodore (Ret’d) Andrew Curtis OBE

RUSI Associate Fellow, Military Sciences