‘County Lines’: The Modern Cyber Slaves of Britain’s Drug-Trafficking Networks

Vulnerable children are being used to peddle drugs in the UK’s rural communities. Efforts to stamp out this form of modern slavery are recording only feeble successes.

Only a few weeks ago, members of a drug-dealing gang were jailed under new UK modern slavery laws, for using children to traffic cocaine and heroin. Missing children are increasingly becoming the modern cyber slaves of the 1,500 drug trafficking routes operating today across the UK. And the cyber sphere, dominated by social media, has become a space through which children are recruited and entrapped into the modern slavery and drug-trafficking worlds.

In March 2019, the All-Party Parliamentary Group (APPG) on Young Runaways and Missing Children and Adults published a progress report noting that local authorities had failed to comply ‘on risks and responses to children who go missing as a result of grooming for criminal exploitation’ (p.16). Hence, the recent parliamentary inquiry launched by MPs is of no surprise. Since the first APPG inquiry in 2012, there has been a 77% increase in the number of children sent to live in care homes out of their local authority areas and miles away from their familiar, social networks (known as ‘out of area’), while the number of children missing from care has doubled to just under 2,000. Uprooting children to ‘out of area’ care homes fosters an environment of social alienation and isolation through which they become easy targets for criminal exploitation. The most prolific exploitation relates to the so-called ‘county lines’ drug-trafficking operations.

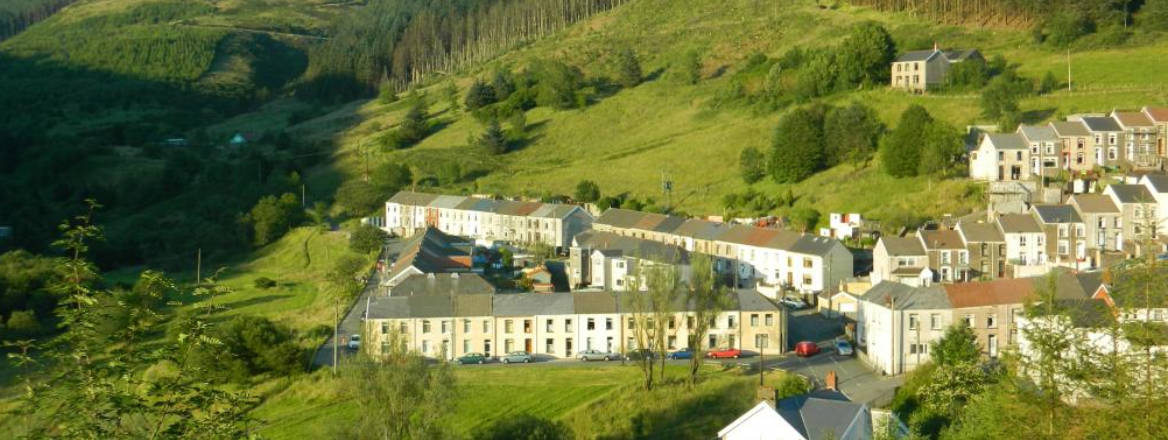

‘County lines’ is a neologism for organised crime groups (OCGs) who, due to a saturation of drug supply in their home cities, have expanded their networks to the provincial countryside, where an existing demand and profitable drug market is identified. Children are groomed (as runners, mules and dealers) to deliver and traffic Class A drugs into rural county towns. The less intensive policing in these areas, due to the continuous cuts to police funding, is another incentive for the expansion. As county lines show, drug trafficking does not need to cross an international border, but rather, can hinge on a domestic one: urban and rural. Similarly, the UK children’s care system also rests on an urban–rural divide, due to its monopolisation by profit-driven private companies. Here, many inner-city children are moved cross-boundary to provincial rural towns (‘out of area’) where care home properties are cheap and overheads are low. Recruiting children into county lines is also motivated by profit maximisation and allows OCGs to pay minimal sums or no money at all.

Ultimately, there is a link between ‘out of area’ care home placements and missing children that are criminally exploited in county lines. According to the NGO Anti-Slavery International, modern slavery does not always appear in the obvious form in which one person literally ‘owns’ another. Rather, modern slavery adapts to societal circumstances, but always affects those vulnerable to being taken advantage of and concerns the loss of their free will. There is a dominant perception that victims of modern slavery are still in shackles and chains, and thus, children running drugs on trains with new smartphones could not possibly be in that dire situation. However, being placed in care homes far from their familiar social networks leaves such children isolated, a factor that often causes them to run away, making them vulnerable to being taken advantage of as modern slaves by OCGs for county lines.

The APPG progress report and parliamentary inquiry noted that children are first lured into county lines through free gifts such as smartphones and drugs, with intimidation or violence soon following. However, both overlook the crucial role of new digital technologies and social media in the ‘carrot-and-stick’ approach of county lines. In many cases, social media is the means by which children are recruited and entrapped as modern slaves into county lines. Children no longer need to be in direct physical contact to be targeted; they can be contacted through their digital ‘second selves’. This poses a serious threat to national security because governmental bodies are now trailing two bodies, a physical and a digital. While it is easier for law enforcement to build physical frontiers around these children, it is far more difficult – if not logistically impossible – to continuously monitor the infinity of the cyber sphere and every vulnerable child’s contact with it.

As a recent study has highlighted, OCGs have adopted prevalent business strategies, such as mass marketing text messages to advertise drugs, brand recognition via social media and dedicated mobile phone numbers, known as deal lines, as their ‘brand numbers’. Through such strategies, OCG members have amassed huge followings on social media sites, becoming ‘social media influencers’ to vulnerable children in these areas. These sites act as recruitment channels through which OCGs broadcast and glamourise their lifestyle, posting images of children in ‘trap houses’ with new smartphones, clothing items and stacks of money. Social media provides OCGs with the opportunity to increase their power along multiple dimensions, such as accruing larger financial profits and political capital unfilled by the government, by obtaining support from the local youth. For example, it is much harder for law enforcement to track down and obtain the evidence needed to prosecute OCGs when they have a loyal fan base of vulnerable children fortifying and protecting them. Accurate human intelligence is essential to combat drug trafficking or any major organised crime. Hence, this not only poses a major blind spot to national security, but also has profound negative consequences for the local area’s stability and security.

With government influence already retreating in such provincial areas, county lines can easily terrorise the daily life of these communities. Alongside easy access to digital communications channels, OCGs effortlessly recruit and entrap neglected and isolated children. Debt bondage starts to engrain itself when the young runner works to pay off the debt of drugs they have become addicted to or the ‘gifts’ they have been given. Other times, violent and humiliating videos of the child are put online to ensure compliance. Hence, the smartphone becomes a tool of coercion through ‘remote mothering’, whereby the child’s drug runs on trains and minicab services are monitored through smartphone trip-tracking apps or are forcibly live-streamed on video calls. Evidently, technology and the cyber sphere are heavily embedded into the county lines world. It is through such technological methods that children become modern cyber slaves as, with their online and offline worlds becoming blurred, victims are under constant surveillance and lose their free will. While law enforcement can legally request, through a valid warrant, to search and shut down an OCG’s social media accounts and deal lines, other ones simply reappear in their place. As academics at LSE IDEAS have noted, OCGs simply adapt their methods according to law enforcement crackdowns and disruptions of routes.

Prosecution of county lines under the Modern Slavery Act 2015 has certainly helped criminalise the actions of individuals involved, as shown in the first case in December 2017 and the most recent in May 2019. However, those convicted tend to be young adults rather than more senior OCG members, who are better protected against law enforcement with resources, such as inexpensive, pre-paid burner phones that are designed for temporary use and discarded afterwards, than those lower down the rung. Those convicted are also most likely to have been county lines children themselves, who proceeded from slave to master instead of victim to survivor. Hence, prosecution under the Modern Slavery Act simply alleviates the symptoms rather than tackling the problem and its security consequences. In all its guises, modern slavery affects those vulnerable to being taken advantage of; addressing the root vulnerabilities is crucial to safeguard children from being drawn into a life of county lines criminality.

The often-precarious state of the economy in these rural county towns enables county lines to provide a livelihood and employment for the local vulnerable children. When there are no legal economic alternatives in place, the government’s strategy of targeting the drug supply, by prosecuting individuals or destroying resources, is not productive or sustainable in the long term. Rather, policies that foster viable communities, livelihoods and opportunities – policies that focus on the victims, such as accommodation support – are more productive and sustainable as they take children out of an exploitable position. While each community is different, what undermines county lines is reducing vulnerability and creating environments that put communities in control.

The views expressed in this Commentary are the author’s, and do not represent those of RUSI or any other institution.