Brazil’s Drugs Trafficking is Ignored at Europe’s Peril

A bloody prison riot in Brazil has highlighted the country’s growing role as a staging point for illicit drugs heading for Europe. While the EU has done a great deal to disrupt drug routes across the Atlantic, more attention needs to be paid to comparable developments in Brazil.

A prison riot at the beginning of the year in Brazil’s Anisio Jobim Penitentiary Complex (Compaj) in the region of Manaus (Amazonas state) saw at least 56 people killed and around 100 prisoners escaping.

Sergio Fontes, head of public security for the Amazonas state, stated that ‘what happened in Compaj is another chapter of the war that drug trafficking imposes in this country and shows that this problem cannot be faced only by [Brazilian] states’.

The riot was sparked by inter-gang warfare between the First Capital Command gang and a local Amazonian crime group Family of the North; the two often vie for control of the drug trafficking routes and internal prison drug markets.

This ongoing war has extended to the border between the Brazilian state of Mato Grosso and Paraguay, in what is believed to be the largest illicit drugs gateway into Brazil.

Consumption and trafficking alike have been on the rise in Brazil in recent years. In 2015, an investigation by the Guardian found that Italian organised crime gangs were facilitating the trafficking of drugs from Latin America to Europe through Brazil (and Africa).

This was a result of enhanced international and regional efforts to control trafficking in Colombia and other drug producing nations.

‘The all-powerful Calabrian crime syndicate ‘Ndrangheta has forged a deadly network of drug trafficking routes through Brazil – 80% of all cocaine arriving in Europe comes through the country’s Santos port', the Guardian claimed.

Consequently, the effects of the battles for control of drug trafficking routes are felt at several different levels. First, narcotics wars exacerbate an already complicated situation in Brazil’s prisons due to overcrowding and the authorities’ inability to separate opposing gangs, or control drug use.

Second, the harsh drug laws applied in most of Latin America perversely mean that low-level criminals make up the biggest sector of prison population. This ultimately fuels even further drug demand without having a significant effect on countering trafficking networks.

It is important to note that, since 2006, Brazil’s drug legislation had decriminalised consumption in the hope that this may reduce the disciplinary burden on prisons.

However, in practice, the law is still not being properly implemented, if only because it is often difficult to distinguish between users and traffickers, who are still deemed to engage in a criminal activity.

Third, incidents of violence and drug trafficking in the Amazon region in particular with its hidden routes to Peru, Bolivia and Colombia for drug traffickers have been rising in recent years. Brookings Institution research last year indicated that ‘more than half of the cocaine seized in Brazil came from Bolivia (54 percent), followed by Peru (38 percent), and Colombia (7.5 percent)’.

The impact of drug trafficking in the Amazon region – and especially in Brazil – not only boosts other illicit activities but also directly impacts on the country’s environment and eco-system. For example, there have been examples of groups of indigenous people from ‘uncontacted tribes’ being put at risk or even being displaced by cartels operating in remote regions.

Finally, the relationship between the growing drug use in Brazil and its importance as a route through West Africa is a direct threat to Europe.

Recent reports of ongoing connections between Nigerian criminal groups and the drug kingpins in São Paulo confirm the inability of the authorities on either side the Atlantic to prevent trafficking and cooperate effectively.

For the EU-funded Cocaine Route Programme, the surge in tensions and drug-related violence in Brazil serve as an indication of the ‘displacement’ of violence and drug trafficking activities.

However, the identification of Brazil as a drug route and the need for subsequent action have not yet received the attention they deserve.

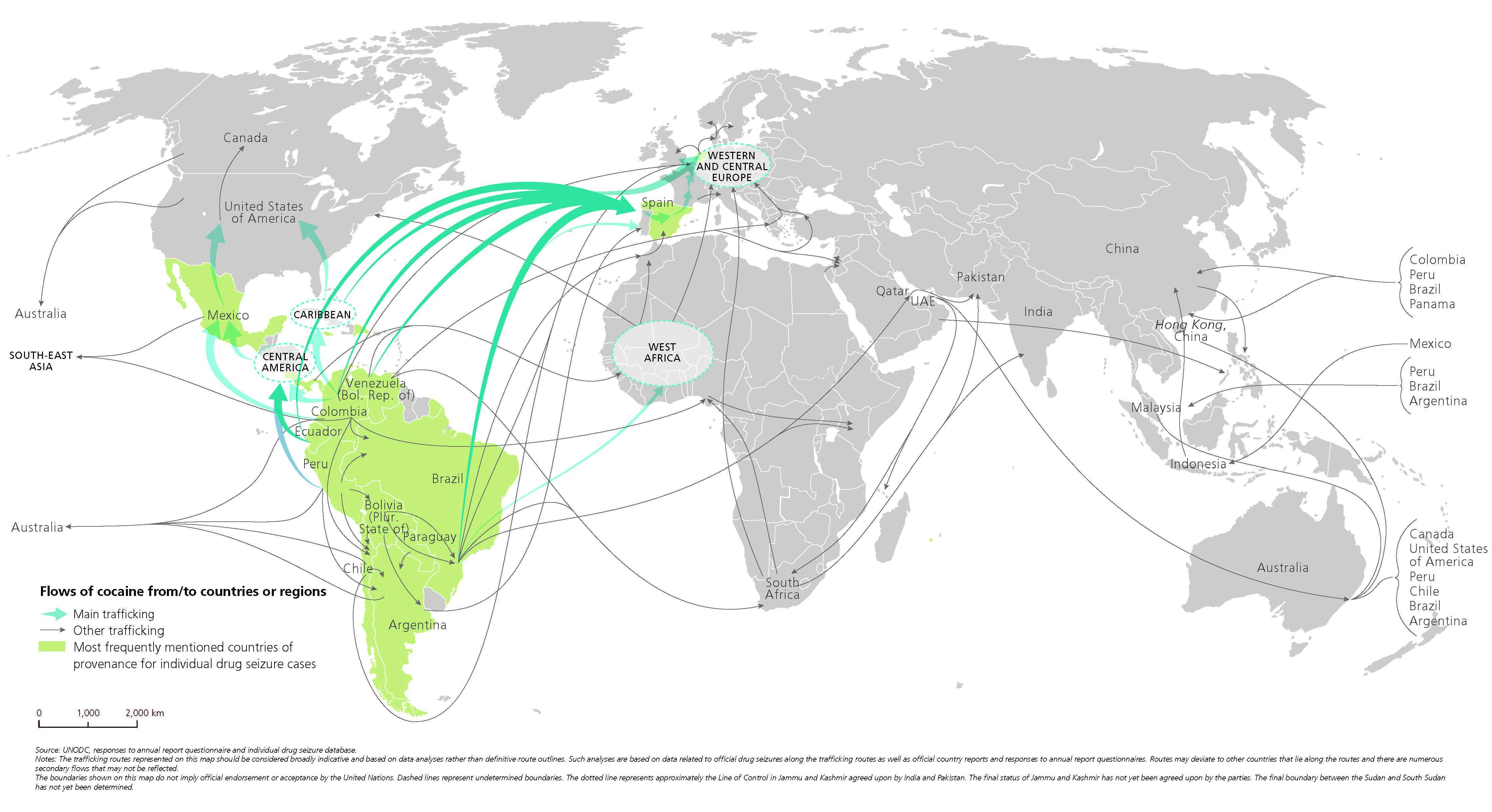

As this UN map illustrates, the UN’s World Drug Report confirms this lack of attention, but also the fact that Brazil’s role continues to go largely unnoticed as an emerging route and facilitator of trafficking.

As the Brazilian economy continues to slide into recession and a swingeing austerity programme is implemented, the numbers of those engaged in criminality (illegal gold mining and drug trafficking being the two most prevalent activities in border regions) is likely to continue to rise. In sum, while Brazil falls outside of EU bilateral cooperation programmes, its importance as part of the cocaine route to Africa and the EU must be emphasised and acted upon using the available thematic tools and within the context of a trans-regional approach.