Back to the Future: Applying the Chilcot Checklist to Ukraine

As the Prime Minister considers sending UK troops to Ukraine, assessing his options with the Chilcot checklist suggests the mission must not go ahead.

In 2016, Sir John Chilcot published the ‘Report of the Iraq Inquiry’. The 2.6-million-word forensic investigation covers the political and military dimensions of the 2003 Iraq War and all UK government departments that were involved. He concluded:

‘The decision to use force – a very serious decision for any government to take – provoked profound controversy in relation to Iraq and … continues to shape debates on national security policy and the circumstances in which to intervene.’

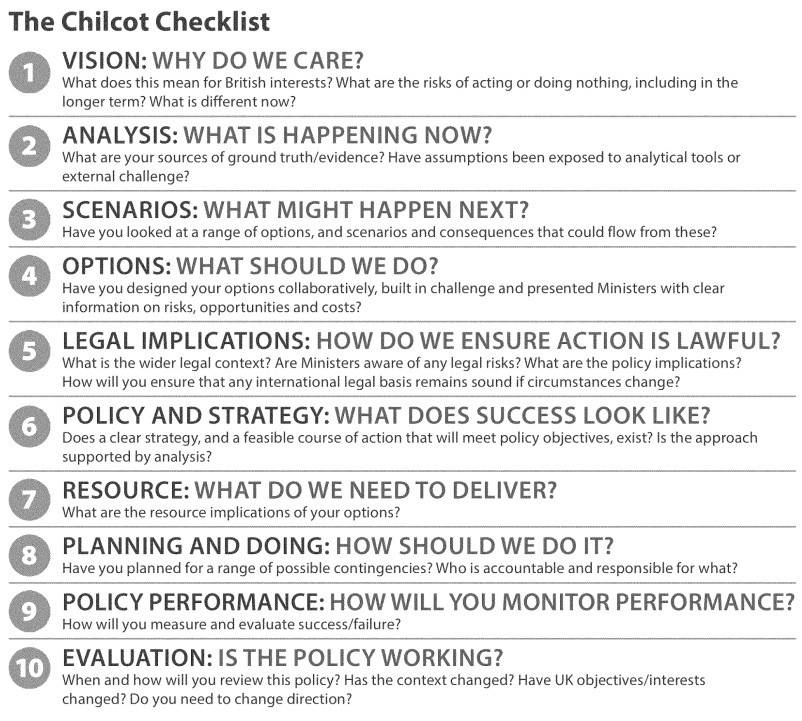

In 2017, the Ministry of Defence (MoD) adapted the magnus opus into ‘The Good Operation’ handbook ‘to prompt its readers to ask the right questions as they plan for and execute a military operation’. Contained within is a 10 point ‘Chilcot Checklist’ which explicitly invites challenges to the plan where concerns are held. If applied retrospectively to recent UK operations in Afghanistan from 2006 (when the UK led the decision to significantly expand the NATO operation to a country-wide strategy) or Libya in 2011, it is clear – especially with hindsight – that they should not have even been attempted.

At present, it is highly unlikely that Ukraine will receive US security guarantees and therefore it is increasingly likely that a European military force will be required to deploy to Ukraine to deter Russia and support a ceasefire and subsequent attempts to forge a path to conflict resolution, if not peace. Russia – and the US under its current leadership – would not agree to a NATO operation. The EU lacks the capabilities, experience and maturity to do it, even if the Berlin+ agreements were activated to allow the EU the use of the NATO command structure. This leaves some form of a ‘coalition of the willing’ as the only option.

We do not yet know the requirement, but potential options range from a small ‘tripwire’ force, to a multinational Division, initially of 20,000 troops, a 30,000-40,000 strong ‘reassurance force’, or at the top end a 100,000 plus �‘traditional peacekeeping force’. Europeans might be able to do the first three on their own – especially with Turkish support – but a global force would likely be required to sustain the latter option.

Sir Keir Starmer is already leading on building a coalition of up to 20 countries. In doing so, it is imperative that the Prime Minister makes the Chilcot Checklist front and centre of the decision-making. While very familiar to military officers and MoD civil servants, it must be brought out of the dark and into all government departments and internationalised to coalition partners. With key New Labour figures from 2003 back in government - UK Ambassador to the US Lord Mandelson and National Security Advisor Jonathan Powell – the Prime Minister can call on valuable and rare institutional memory of how the UK government got decisions between 2001 and 2003 drastically wrong.

Unlike in 2003 – where flawed intelligence and its management were ultimately responsible for the policy failure - the situational awareness now is much clearer

Evaluating the potential mission for the UK in Ukraine though the checklist, currently only two are satisfied, a further two are developing, and six are not even close to being satisfied. Time is also against Europe, but the Prime Minister must not cut corners. The full list should be satisfied before he takes the decision to Parliament.

The Case for Intervention

The first two principles are the strongest case for intervention and are arguably already satisfied.

First, ‘Vision: Why do we care?’: The Prime Minister is clear that ‘the future of Ukraine is vital for our national security’ and is firmly in UK national interest. He is supported by his electorate with UK public concern and support for Ukraine still very high. Supporting a ceasefire and path to peace in Ukraine is also morally right and firmly within UK values as Russia is the clear aggressor and continues to deliberately target Ukrainian civilians across the country. Moreover, it is also consistent with long-term UK strategy which has supported Ukraine militarily since the annexation of Crimea in 2014, and the UK’s current role as the third largest provider of military, humanitarian and economic assistance.

Second, ‘Analysis: What is happening now?’: Unlike in 2003 – where flawed intelligence and its management were ultimately responsible for the policy failure - the situational awareness now is much clearer. Indeed, the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine reclaimed public trust in the UK-US intelligence relationship which was lost after 2003. The Prime Minister is acutely aware of the gravity of the situation and described it as a ‘pivotal moment’ for Europe when he announced a recent uplift in defence spending to 2.5% of GDP by 2027.

The moral imperative is clear, and similar arguments were made for intervening in Afghanistan and Iraq, alongside other post-Cold War ‘humanitarian’ operations. However, the decision to deploy military force must be grounded in the reality of what is militarily achievable, by when this can be done, and, crucially, what to do if something goes wrong.

The Developing Situation

Principles 3 and 4 are being developed in real-time between the US and Russia, who are bilaterally setting the requirements, with European countries struggling to influence matters from the outside. Therefore, it is critical that the UK and European allies have a stake in the negotiations to shape a ceasefire which they can protect. This should be the Prime Minister’s leading request to President Trump.

Both ‘Scenarios: What might happen next?’ and ‘Options: What should we do?’ are fundamentals of defence planning. It is the process of assessing the situation and developing ‘courses of action’ and a ‘concept of operations’ for the mission. These will change and be refined not only up to a potential deployment, but also when deployed in theatre, as the situation changes. Critical to a successful coalition of the willing is a broad agreement of the risks, opportunities and costs of an operation, and the equal burden-sharing among contributors.

The greatest risk is that governments in 2025 might have to sign up for an open-ended commitment. While not completely analogous to the situation in Ukraine, 28,500 US troops are still stationed in the Republic of Korea – 72 years after the armistice was signed. In addition, the NATO Kosovo force (KFOR) is still active 26 years after the intervention and the UK still periodically reinforces the mission such as in 2023.

With no clear end in sight, the Prime Minister would be asking Parliament – and his partners – to take an unprecedented leap of faith. Before he does this, the scenarios and options must be crystal clear.

The Case Against Intervention

The final six Chilcot principles – on a current understanding of the potential operation – provide very strong arguments and challenge against deploying a UK-led force to Ukraine.

First, ‘Legal Implications: How do we ensure action is lawful?’: Securing a UN Security Council mandate for the operation would be challenging, but not impossible, especially with Trump’s bending of the knee to Russia since his inauguration. Moreover, in a coalition of the willing there is always the danger that each participating country brings with it legal definitions – especially if they are not exclusively European states. Moreover, caveats to deployment can also hinder effective working and risk profiles, which plagued operations in Afghanistan and elsewhere. It is an important consideration that a UN mandate might give the mission legitimacy, but it is not a guarantee of mission success.

Second, ‘Policy and Strategy: What does success look like?’: This is fundamental as, simply put, the mission cannot fail. If it did, the loss of credibility for Europe, and by extension to NATO and the EU, would likely undermine European security to the point that it would completely unravel and hand decisive strategic advantage to Russia.

The key requirement for the Prime Minister is the master principle of war - ‘selection and maintenance of the aim’. However, three years after the invasion, none of the four UK Prime Ministers have been able to articulate exactly what Ukrainian victory – and Russian defeat – looks like. A favoured tagline is that the UK will support Ukraine ‘as long as it takes’ without actually defining what ‘it’ is. Therefore, the Prime Minister must develop, agree, and ruthlessly enforce the mission objective.

Third, ‘Resource: what do we need to Deliver?’: The minimum contribution for the UK would be a Brigade (5,000), alongside a lion’s share of the command and control, Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance assets and logistics enablers. But it would require 15,000 to sustain this force indefinitely (one in theatre, one recovering and one training) or 20% of the total British Army strength and approximately 50% of the Field Army. Committing this force to an open-ended operation would effectively be permanently removing these troops from the British Army order of battle. As such, it would put a UK ‘NATO first’ strategy in jeopardy and the commitment to be the Alliance’s strategic reserve. Moreover, it is not just a question of numbers – this force are not peacekeepers. They need to have the full heavy suite of military equipment available to deter Russian attacks, and – if required – to fight and fix Russian forces in Ukraine if a wider war between NATO and Russia originated in the Nordic or Baltic states.

The consequences of mission failure would be fatal to European security

Fourth, ‘Planning and Doing: How should we do it?’: The UK cannot lead alone and a Franco-British political and military leadership team appears to be emerging. The UK and France are extremely close allies, both backed by nuclear forces, both deployed at Brigade level previously (UK in Afghanistan, France in the Sahel), and have the Combined Joint Expeditionary Force (CJEF) as a crucible of interoperability between the two militaries. As such, they remain the only two true framework nations of Europe which are capable of commanding.

However, while this construct sounds feasible, if challenging, it is likely insufficient. A Two-Star Headquarters would be too small for such a deployment and the CJEF is optimised for crisis management – not defence and deterrence. Therefore, it would have to both scale – to a Divisional level - and re-role to defence and deterrence prior to any deployment which would take a significant amount of time. The potential political pitfalls are greater than the military challenges. If Le Pen wins the 2027 Presidential Election and then withdraws the French contingent from the mission, it will put the UK in a lonely command position, regardless of the hit to resources. Such an eventuality could be fatal for mission success and is something President Macron cannot guarantee, no matter how committed he is.

Finally, both ‘Policy Performance: how will you monitor performance?’ and ‘Evaluation: Is the policy working’ are ultimately about measuring performance and success criteria. Without knowing the mission, it is impossible to evaluate these. However, once the UK is committed it cannot withdraw, vastly reducing the options available to it. As the leading country, the UK will be impacted by failure the most.

The Worst-Case Scenario

The Prime Minister is in an invidious position. He must prepare for a potential UK-led mission. However, in preparing for it, he also makes it more likely, as Trump will regard it as an option available to him. However, the consequences of mission failure would be fatal to European security. It would be better to not even attempt an operation at all, rather than get bounced into a poorly defined mission by Trump and be left with the consequences. Wanting to finalise the blueprint for the coalition of the willing this week, ahead of any US-Russia-Ukraine deal, only increased the risk of a poorly developed operation from deploying and therefore also succeeding.

More recent memories than 2003 also cast a long shadow. The 2021 chaotic fall of Kabul was a direct product of a bad Trump Doha deal with the Taliban. Yet, Afghanistan was always a discretionary operation, with peripheral interest to the UK – loosely recognised as support to the US. However, this support did not stop Vice President JD Vance’s recently disrespecting UK and French troops by saying a US minerals deal was a "better security guarantee than 20,000 troops from some random country that hasn't fought a war in 30 or 40 years", demonstrating how fickle the US can be in its leadership and outlook. Over-committing UK troops to uphold US foreign policy was as bad a policy after 9/11 as it is now.

Finally, a truism of military planning is that ‘the enemy gets a vote.’ Indeed, putting static and open-ended European forces into Ukraine – that are explicitly not covered by NATO’s Article V – provides Putin a delicious opportunity to weaken the Alliance. It is anything but a deterrent. He will use the full levers of his military and special services to undermine the operation with an inability for the Europeans to respond in fear of escalation. At its most dangerous, he might choose to deliberately target European forces but insist that such attacks were the result of technical failures or misunderstandings, challenging the Europeans to respond. Each event would serve to undermine the strength of European commitment in the face of Russian aggression and would indirectly cut away at the credibility of Article V even when it was not enforceable.

© RUSI, 2025.

The views expressed in this Commentary are the authors’, and do not represent those of RUSI or any other institution.

For terms of use, see Website Ts&Cs of Use.

Have an idea for a Commentary you’d like to write for us? Send a short pitch to commentaries@rusi.org and we’ll get back to you if it fits into our research interests. View full guidelines for contributors.

WRITTEN BY

Ed Arnold

Senior Research Fellow, European Security

International Security

- Jim McLeanMedia Relations Manager+44 (0)7917 373 069JimMc@rusi.org