The current health crisis has compelled the Institute to postpone its annual Gallipoli Lecture to later in the year. Nonetheless, the Institute wishes to mark Anzac Day, as an honour to the sublime sacrifice of our Australian and New Zealand allies more than a century ago, and ever since.

Formally, Australia’s national day is on 26 January. This commemorates the landing of the first fleet from England in 1788 which established the initial European settlement in Australia. Australia Day, as it is called, is a national holiday, a day on which Australians get together in the middle of summer to enjoy the beach, barbecues at home and the announcements of Australians of the year and national honours lists. A tiny minority of activists always create controversy on Australia Day saying Australian should not commemorate what they call invasion day. But most Australians don’t buy that agenda.

The day that is beyond controversy and which is more deeply felt as a national day is Anzac Day – 25 April. It’s very much in the Anglo-Saxon tradition to remember and commemorate great military failures and Anzac Day certainly does that. It commemorates the landing of Australian and New Zealand troops at Gallipoli on 25 April 1915. The Gallipoli campaign was a failure and thousands of Australians and New Zealanders were killed on that far off Turkish peninsula.

Australians participated in many other battles during the First World War and some of Australia’s battles were gloriously victorious. So why is it that Australia commemorates the landings on Gallipoli rather than some great military victory?

The answer is quite clear. In 1901 the six colonies of Australia came together and created one nation, the Commonwealth of Australia. The federal government was given responsibility for the armed forces. An army was created, a navy built – or bought from Britain, to be precise – and then the First World War broke out in 1914. Australia immediately rallied to Britain at the outbreak of war and pledged its army and navy to support the British Empire in its time of need. The Australian troops, who were all volunteers, were initially sent to Egypt.

It was from Egypt that the Australian troops embarked for Gallipoli. The plan was to seize the Dardanelles and then launch an attack on Constantinople, thereby knocking the Ottoman Empire out of the First World War. The landing at what is now called Anzac Cove on the Gallipoli Peninsula at dawn on 25 April was the first time what was then called the Australian Imperial Force saw action. It was, to put it another way, the first time Australia had acted as a nation on a battlefield.

Although an estimated 40% of the Australian soldiers who landed at Gallipoli on Anzac Day in 1915 were born in the UK, this landing was seen as symbolic of the birth of a nation. Up until 1915, Australians, other than the indigenous population, regarded themselves as Britons living in Australia. There was no strong sense of separate national identity. It was the Gallipoli landings which gave birth to that sense of a separate identity. That makes Anzac Day a very special day for all Australians.

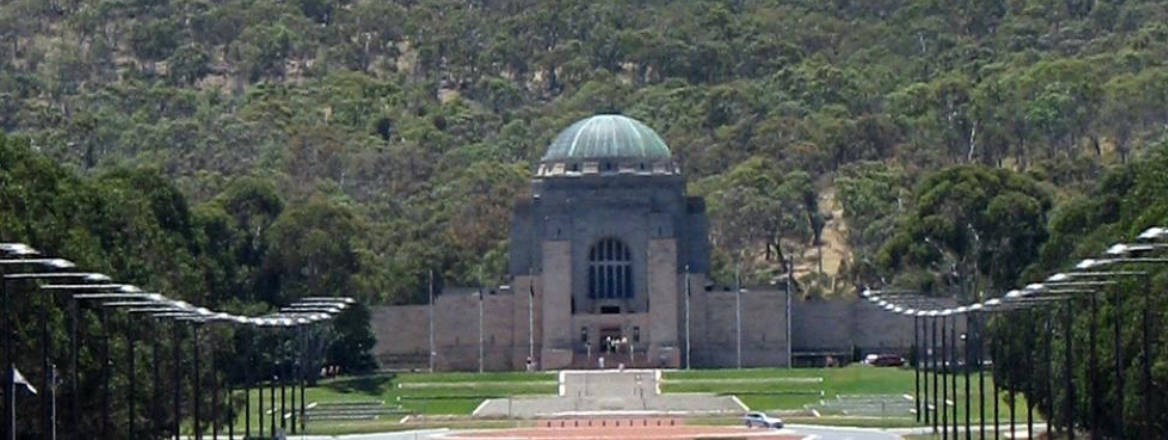

Since the First World War, Anzac Day has come to be a day of solemn reflection on the sacrifices that so many Australians have made over the years to the national cause. At dawn every Anzac Day millions of Australians flock to the war memorials sprinkled around the suburbs and towns of the country. There is barely a settlement anywhere in Australia which lacks a war memorial. There engraved are the names of Australians who have served and died for Australian values and Australian interests. They stretch from the First World War to the Second World War, Korea, the Malayan emergency, Vietnam, right up to the Iraq wars and Afghanistan.

Anzac Day services are religious and brief. A church minister usually leads a service which includes a hymn or two, a reading from the Bible and a very brief sermon. The services are non-denominational and the audience at each service is invariably dotted with people who have served or are still serving in the Australian armed forces.

Numbers at Anzac Day services have grown over the years, not diminished. These days, many young people climb out of bed at 5:30 in the morning to attend their local Anzac Day service, recognising the sacrifices of those who have gone before them.

After the Anzac Day dawn service, there is a traditional breakfast which includes coffee laced with rum.

Anzac Day commemorations are organised, typically through Australian embassies and high commissions, all over the world. In London, the day begins with an Anzac Day service at the Australian war memorial at Hyde Park Corner. This is attended by the Australian and New Zealand High Commissioners and also a member of the royal family. Later in the day, a commemorative service is held at Westminster Abbey and at the end of the day there is a reception at either the Australian or New Zealand High Commission. The Anzac Day dawn service at Hyde Park Corner, which begins at around 5am, is attended by thousands of Australians and New Zealanders either living in or visiting London at that time.

Political leaders tend to use Anzac Day to reaffirm the commitment of Australians to the nation’s core values. They speak of the importance of democracy, civil liberties and human rights and respect for the individual. As is always the case in Australia, there is a sub theme of egalitarianism: of the equal value of all individuals regardless of their rank, station in life or wealth.

Anzac Day is also a reminder of the symbolic importance of the Australian Defence Force. The Defence Force has, of course, a very practical function, but members are seen by most of the public as symbolic of the nation.

Australia was not a nation born through revolution or war, but it is a nation which gained its strong sense of identity at war. That is why Anzac Day has a very special importance, exceeding both Australia Day and Remembrance Day.

Alexander Downer is a Distinguished RUSI Fellow and was Australia’s longest-serving Minister for Foreign Affairs, and subsequently also served as High Commissioner in London.

The views expressed in this article are the author's, and do not represent those of RUSI or any other institution.

WRITTEN BY

The Hon. Alexander Downer AC

Former RUSI Distinguished Fellow