Friends, Sponsors and Bureaucracy: An Initial Look at the Daesh Database

A preliminary analysis of leaked Daesh recruitment files by RUSI experts suggests that the social processes underlying the radicalisation and mobilisation of foreign fighters still mirrors those of Al-Qa’ida.

In March 2016 it was revealed that a defector from Daesh (also known as the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria, ISIS or IS) had obtained a memory drive containing the personal details of thousands of foreign fighter recruits. Sky News has shared the information with RUSI, and while its researchers are still conducting detailed analysis of the records, a preliminary examination has revealed a number of insights.

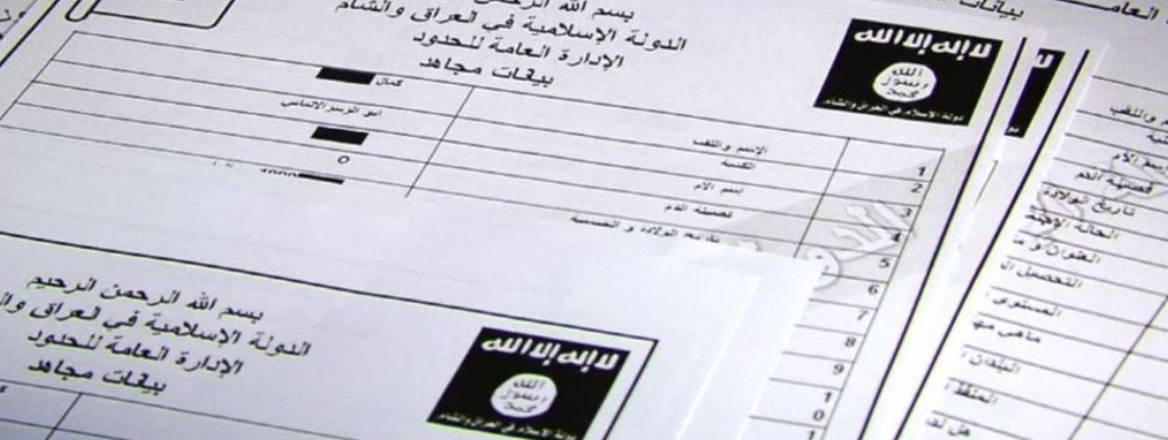

The majority of the documents appear to be arrival forms, completed by or for Daesh recruits as they sought entry into Daesh-controlled territory between early 2013 and late 2014. They are bureaucratic in nature, with 23 fields recording details from basic biodata to level of Sharia-related knowledge; there is even a space on the form where the date of the individual’s death can be entered, should the recruit die while fighting with Daesh.

While of evident value, it is important to acknowledge the limitations of this database. They offer only a partial snapshot of those who travelled to Syria and Iraq – it is impossible to know how many others travelled during this period, or how this specific dataset compares against the broader picture. Nevertheless, they provide important details not only about individuals but also about how Daesh administers its territory; about the recruitment, radicalisation and mobilisation of foreign fighters; and about how the group has learned from the experiences of its precursor organisation, Al-Qa’ida in Iraq (AQI).

A Militant Bureaucracy

Examining the format of the documents, it is clear that they represent an attempt to impose control and implement state administration. There are some similarities with AQI’s practices: these forms record similar information to that found in the AQI archive known as the ‘Sinjar records’, including the recruit’s route of entry, his or her facilitator and the personal belongings being deposited.

There are also indications that AQI’s initial model has been further developed to record the knowledge and experience of incoming fighters. There are additional fields, not found in the Sinjar documents, to record the recruit’s level of Sharia knowledge and his or her previous experience of jihad. There is also evidence that further notes were made to record any potentially relevant skills or knowledge beyond those relevant to combat.

The bureaucracy of ‘state’ administration points to the dual nature of Daesh. As the group has come under increasing military pressure in Syria and Iraq, it has amplified its efforts to inspire, instigate and direct attacks against the West. Former Director General of MI5 and RUSI Senior Associate Fellow Jonathan Evans has categorised this strategy as ‘chaotic terrorism’, with some attacks directed by the group, but many undertaken by ‘disparate individuals who may have no actual contact with the group but are encouraged through its propaganda’. There are therefore stark contrasts between these dual roles: Daesh is simultaneously a tightly controlled and bureaucratic ‘state’, and a loosely controlled ‘chaotic’ global terrorist movement.

With a Little Help from My Friends

Examining Al-Qa’ida’s recruitment practices, Marc Sageman encapsulated the importance of social bonds in what became known as his ‘bunch of guys’ theory. He showed that bonds of kinship, or friendship, often predate recruitment and radicalisation. Similarly, anthropologist Scott Atran’s research finds that kinship and friendship are crucial to understanding why people radicalise and embrace violence: ‘people don’t simply kill and die for a cause. They kill and die for each other.’

Daesh has skilfully exploited social media to spread their message to a global audience; however, as Peter Neumann at the International Centre for the Study of Radicalisation (ICSR) has argued, social media is a powerful propaganda tool but it has not displaced the importance of these real-world connections in mobilising people to action. Initial analysis of the leaked documents reinforces this insight, revealing evident geographic clustering within foreign fighter recruitment.

Just as analysis by the Combating Terrorism Center (CTC) of the Sinjar records revealed a high proportion of AQI recruits arriving on the same day as others from their hometown, these documents show many British fighters arriving in groups. The fact that some of these groups hail from the same place, with notable concentrations from Coventry, Cardiff and Portsmouth, underlines the importance of offline interactions in radicalisation; were social media the crucial element, then (as Neumann has explained) recruits would be dispersed across the country rather than clustered in specific locations.

A Word from the Sponsors

Moreover, the documents confirm that in gaining admittance to Daesh-controlled territory, it is necessary to declare a sponsor. Like Al-Qa’ida before it, Daesh seeks to verify the identity of its new recruits to limit possible infiltration. One individual who appears in this role is particularly noteworthy: Omar Bakri Mohammed, the Syrian preacher who founded the group Al-Muhajiroun in the UK in the late 1990s (an extremist group that was later proscribed in 2010). In the wake of the July 2005 bombings, he fled the UK, and was subsequently barred from returning by the Home Secretary.

From his base in Lebanon, Omar Bakri appears to have continued his radicalising activity. While this is not a new revelation, it is striking that he is cited as a sponsor numerous times in the Daesh database. Previously dismissed as a ‘loud-mouth’ – most amusingly characterised as the ‘Tottenham Ayatollah’ in Jon Ronson’s 1996 television documentary – Bakri now appears able to facilitate access to Daesh. This highlights the continuing threat from charismatic extremists, as well as the persistence of jihadist networks – in this case both still posing a threat more than two decades after their emergence.

Conclusion

Daesh has clearly learned lessons from Al–Qa’ida, and AQI in particular, so that it can hold territory more successfully and more effectively utilise the skills of its recruits. However, the evidence from the Daesh database suggests that the fundamental mechanisms of terrorist recruitment and radicalisation are still the same.

Social media has given the group greater access to a global audience, but the social processes underlying the radicalisation and mobilisation of foreign fighters still mirrors that seen among the recruits of Al-Qa’ida. Behind the bureaucracy, foreign fighters are still just a bunch of guys.

WRITTEN BY

Raffaello Pantucci

RUSI Senior Associate Fellow, International Security