The End of Defence Austerity? The 2019 Spending Round and the UK Defence Budget

While challenges remain, the financial position of UK Defence has improved significantly over the last two years.

The UK Government’s Spending Round announced on 4 September has confirmed the significant shift in the financial fortunes of the Ministry of Defence (MoD) that has been taking place over the past two years.

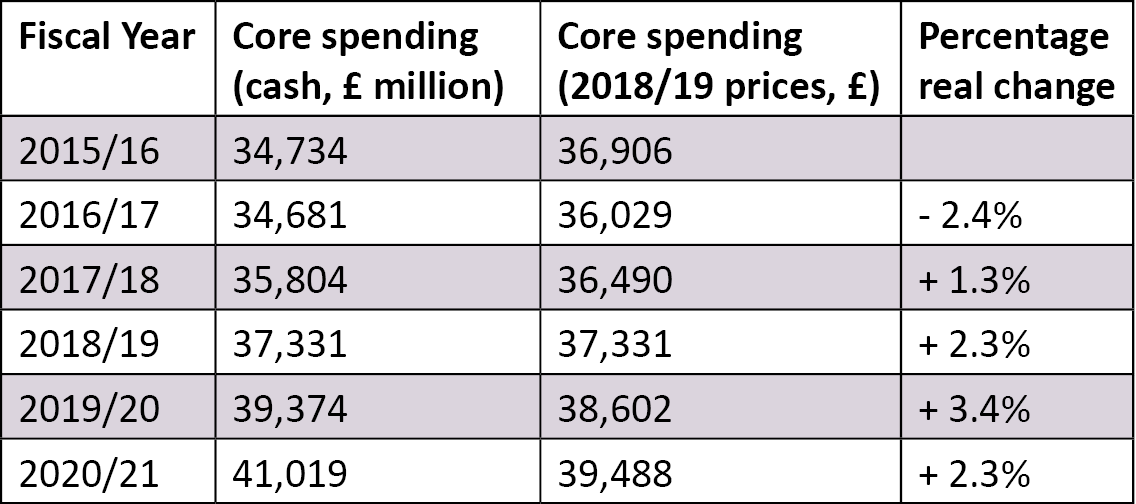

The additional resources for Defence will lead to a real increase in the core MoD budget (excluding operations) of 2.3% for 2020/21, bringing the four-year real-terms increase in core defence spending to some 9.6%, the biggest such increase since the early 1980s (see Note on Calculation and Table 1).

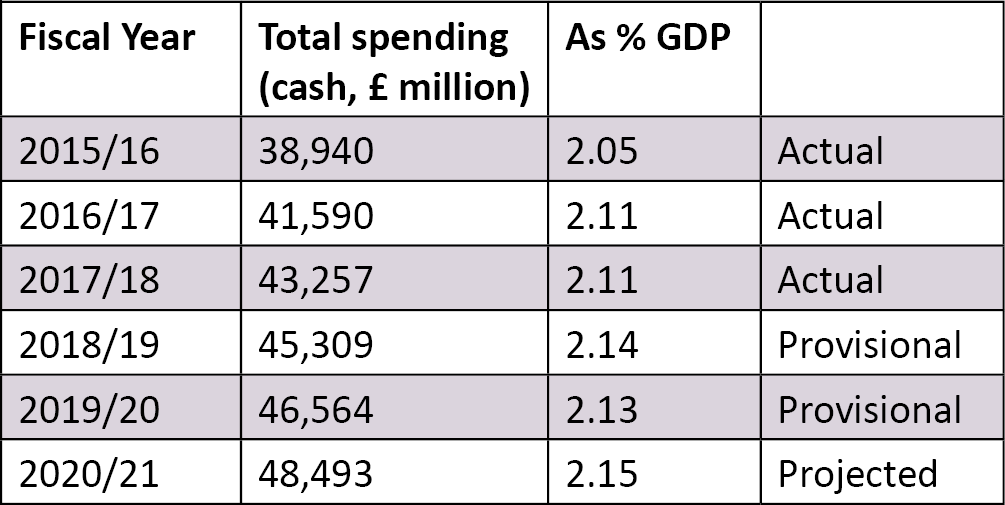

Provided that the 2020/21 settlement is used as a baseline for future Spending Reviews, the UK is set to continue to spend between 2.1% and 2.2% of its GDP on defence for some years to come, proportionately more than any other European member apart from Greece, and second only to the US in absolute terms for NATO members.

On the same baseline assumption, the 10-year £7-billion funding gap in resources available for funding the Strategic Defence and Security Review’s (SDSR) 2015 plans appears to have been closed. Additional resources, or a reallocation between existing priorities, will be needed if new investments in addition to 2015 plans are to be made.

The Spending Round

The publication of the Spending Round for 2020/21 on 4 September was overshadowed by the latest developments on Brexit. The relatively limited coverage in media reporting was focused on the government’s commitment to fund 20,000 extra police, improve funding for schools and colleges, and meet the costs of Brexit. More widely, it heralded a significant shift away from austerity, with departmental day-to-day spending due to increase by 4.1% in real terms: the largest one-year increase for 15 years (see page 1). Departmental capital spending will grow by some 5.0% (see page 5).

Not all parts of government have shared in this new growth. Annually managed expenditure (AME), which accounts for around half of total spending, is projected to decline slightly in real terms, continuing the squeeze in benefits spending that was central to both the 2010 and 2015 Spending Reviews (it should be noted that changes in AME are highly dependent on levels of unemployment and decisions on the rate at which benefits are to be uprated). Total government spending for 2020/21 is thus due to grow by only 2.4% in real terms, allowing the government to claim that it is meeting its fiscal target of keeping the deficit below 2% of GDP.

The Defence Settlement

On defence, the Spending Round announced new spending allocations for both 2019/20 and 2020/21. For 2019/20, a further £300 million was provided, allowing some activities to be brought forward from 2020/21. For 2020/21, the MoD was unusual (along with the Single Intelligence Account) in having had an allocation already agreed in the 2015 Spending Review (other departments only had allocations for four years, hence the need for this Spending Round). Even so, this year’s round added ‘up to’ a further £1,200 million to this inherited allocation, significantly increasing the funds available.

The Spending Round went further, stating that it had provided an extra £2.2 billion for defence (see page 13). But not all these resources are available for additional spending on defence capabilities. This total includes an additional £700 million for extra employers’ pension contributions in order to fund the costs of new actuarial assumptions. Funding for this had already been added to the budget for the previous year (2019/20), and it was clear that it would be needed for 2020/21. It will be important to make sure, however, that both the additional pensions allocation and the additional resources for capability spending provided in the Spending Round allocation for 2020/21 are also included in the baseline for future Spending Review allocations.

In addition to the £41,299 million allocation for 2020/21 announced in the Spending Round, a further one-off allocation of ‘up to £200 million’ for additional Dreadnought costs will be available if programme costs exceed those currently scheduled. This Dreadnought-specific allocation will not form part of the baseline for future Spending Reviews.

Given this decision, and similar decisions made for the last two financial years, the MoD now has a strong case to argue that future annual deviations in Dreadnought spending plans should be funded separately from the £10-billion contingency fund established for the programme in 2015, thus sheltering the rest of its procurement programme from having to make inefficient adjustments in order to accommodate future fluctuations in what is now by far its largest programme (currently spending around £2 billion per annum). The Treasury can reasonably insist, in return, that below-budget Dreadnought spending should also be reflected in the MoD’s annual allocation.

The overall increase in the MoD budget for 2020/21 is a significant shift from the position that had been anticipated in late 2017, when the MoD faced strong pressure to make cuts in key capabilities in order to balance its books for the National Security Capability Review. In the event, in the year that followed the replacement of Defence Secretary Michael Fallon by Gavin Williamson, these cuts were not made.

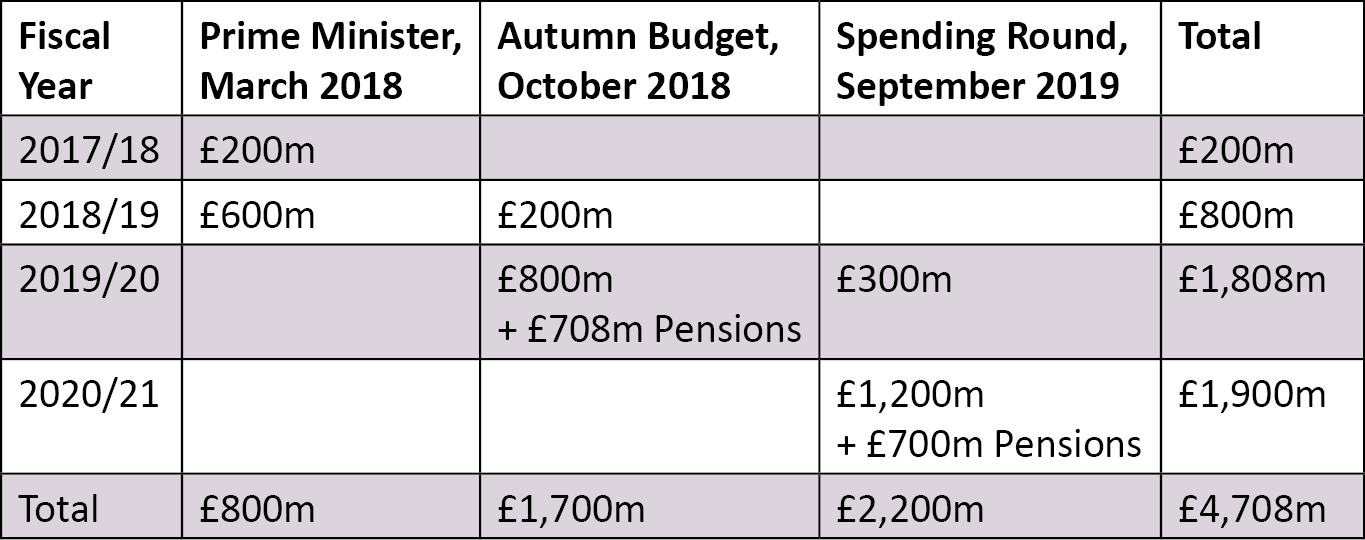

The first sign of a shift came in spring 2018, when Prime Minister Theresa May made new budgetary commitments of £200 million for 2017/18 and increased Dreadnought-related spending of £600 million for 2018/19. The 2018 autumn budget was a further turning point, adding some £800 million to the 2019/20 budget, and topping up the 2018/19 budget with a further £200 million.

When account is also taken of the 2019 Spending Round commitments, the government has now added some £4.7 billion to the MoD settlement for the final four years of the five-year SDSR period: £200 million for 2017/18, £800 million for 2018/19, £1,800 million for 2019/20 and £1,900 million for 2020/21 (see Table 2).

A large part of the first two allocations was for unanticipated increases in spending on Dreadnought construction and to respond to immediately pressing challenges in other areas, holding out the possibility that it would not become part of the permanent budget allocation. One of the most significant aspects of this round, therefore, is that these previously one-off allocations have now been fully incorporated into the budget to be used as the baseline for future Spending Reviews.

This is the most generous spending allocation that the MoD has received for many years. The added funds for 2020/21 announced in this Spending Round mean that core MoD spending will increase by some 2.3% in real terms in one year. Coming on top of substantial real-terms increases in 2018/19 and 2019/20, this will bring the four-year increase in core defence spending (from 2016/17 to 2020/21) to some 9.6% in real terms: the biggest four-year increase for 35 years (see Table 1).

Core defence spending also rose by 9% in real terms over the decade that followed the 1998 Strategic Defence Review (between 1998/99 and 2008/09). But this increase was spread over a much longer period, and in the context of more substantial increases in other areas of public spending.

The injection of some £1.2 billion per year into the 2020/21 budget available for funding defence capabilities would, if sustained after 2020/21, be enough to close the 10-year funding gap for the equipment programme which the National Audit Office had identified in successive reports and has been the focus of much media interest. Moreover, the added funds have allowed the Dreadnought programme to proceed at a more cost-efficient pace, avoiding the stop-start procurement that has plagued some other major programmes in the recent past (notably the carrier at a comparable stage in its procurement in 2007–10, which led to significant extra costs over time).

The government’s commitment to increased defence funding reflects both a response to the new strategic environment (especially growing Russian assertiveness since 2014) and the political unacceptability of further visible reductions in iconic (and important) capabilities, given the experience of the 2010 SDSR.

The UK in Comparison

The new increases will allow the MoD to continue to meet NATO’s 2% target. During the first part of the past decade, despite the UK’s efforts to include further spending items in its NATO reports, spending fell from 2.47% of GDP in 2010 to 2.05% in 2015. Since then, however – helped by a further change in the UK’s NATO’s reporting practices in 2016 – spending has stabilised at 2.14% in 2018 and is due to be some 2.13% in 2019. The additional allocations should bring 2020 spending to some 2.15% (somewhat higher if operations spending remains at recent levels) (see Table 3). This will leave the UK as one of the two biggest European spenders on defence (along with Greece) in GDP percentage terms.

Since the significant cuts in capability announced in the 2010 SDSR began to take effect, the UK’s reputation as Europe’s strongest and most reliable defence power has been dented. This perception added to domestic political pressure for more spending. But it also had the unwanted side-effect of damaging the UK’s reputation with its NATO allies, both in the US and Europe.

This picture is now out of date. The UK continues to have the largest defence budget in NATO Europe, and there is no sign that it is on course to lose this position. France’s defence budget is increasing at a rate (9.7% in real terms over four years) comparable to that of the UK (10.1% over the same period). But France remains stubbornly below NATO’s 2% target, with spending having risen only from 1.79% to 1.84% over the same period.

The UK’s relative position is less impressive compared with the US’s, the main benchmark for whether the UK retains ‘tier one’ status. The latest NATO figures show that UK military spending in 2019 will be only 8.5% of US military spending in the same year. Yet this is nothing new. UK military spending was also 8.6% of that of the US in 1967 (£2,275 million at an exchange rate of £1:$2.80 compared with a US defence budget of $74,210 million), before the withdrawal from east of Suez. It is to the UK’s credit that it has managed to maintain a relatively broad spectrum of capability, and some significant political influence, with a budget of this limited comparative scale.

Future Budgets – Towards the 2020 SDSR

While the MoD has had a good 2019 Spending Round, it is by no means out of budgetary trouble. Provided that the enhanced 2020/21 allocation is treated as the baseline for future years, and further real-terms increases are awarded thereafter, it should be possible to fund the commitments made in the 2015 SDSR. In this sense, the ‘funding gap’ has been resolved. What the Spending Round has not done, however, is provide budgetary resources for the new investments that are likely to be needed, over and above those agreed in 2015, in order to respond to the serious strategic and technological challenges that have emerged subsequently.

In order to review these longer-term plans, the next multi-year Spending Review (and, one assumes, an accompanying SDSR) will be critical. The most credible assumption remains that the MoD will be awarded steady real-terms growth of around 0.5% per annum after 2020/21. Such an increase would, on plausible assumptions on GDP growth, allow the UK to maintain its 2% commitment to NATO well into the 2020s. But it would still require the MoD to make many of the hard choices which it postponed during the recent Modernising Defence Programme review.

Making those choices will be difficult, especially given the resources already tied up in major capital programmes. The MoD now has a year to create the conditions under which sensible decisions are made, allowing it to fulfil its ambitions to create forces for the challenging strategic environment in which the UK is likely to find itself in the 2020s and beyond. But Defence is now in a better budgetary position to face those challenges than seemed likely only two years ago.

Table 1: MoD Spending Trends

Notes:

- Figures are for total Departmental Expenditure Limit (DEL), excluding depreciation, excluding spending on operations.

- Figures for the first four years are outturn figures. The cash figure for 2019/20 is the Main Estimate allocation, adjusted for additional £300 million allocation at Spending Round. The cash figures for 2020/21 is the Spending Round allocation, adjusted for an estimated additional £200 million for Dreadnought and projected net transfers to other government departments at 2020/21 Main Estimates.

Table 2: Allocations to the MoD Departmental Budget (DEL), in Addition to 2015 Spending Review

Notes

- For provisional 2019/20 figure, assumes £330 million for operations spending, as provided for in Main Estimates 2019/20. This figure is likely to increase as a result of additional in-year operational commitments.

- For projected 2020/21 figure, assumes total NATO-counted expenditure remains (as in 2019/20) 17.3% higher than total MoD DEL spending, including £330 million on operations. This figure could increase in the event of additional operations spending.

- Assumes GDP growth of 1.0% in 2020/21, in line with HM Treasury, Forecasts for the UK Economy: A Comparison of Independent Forecasts, No. 387 (London: HM Treasury, 2019).

Note on Calculation

The estimated increase of 2.3% for 2020/21 differs from the real-terms increase of 2.6% announced in the Spending Round, largely because the £41,299 million settlement for 2020/21 includes Joint Security Fund allocations which, at Main Estimates, are due to be transferred out of the MoD to the SIA cyber and other non-MoD budgets. The 2019/20 equivalent to this transfer, projected to amount to some £480 million for 2020/21, has already been made in the baseline figures for 2019/20 used in Spending Round 2019. In addition to the Spending Round settlement, the MoD has been allowed to spend up to £200 million in 2020/21 on above-plan Dreadnought costs.

Malcolm Chalmers is Deputy Director-General at RUSI.

The views expressed in this Commentary are the author’s, and do not represent those of RUSI or any other institution.

WRITTEN BY

Malcolm Chalmers

Former Deputy Director General, RUSI